Health & Science

Raising doubts about mammograms; Extinction in a flash; Printing cells that work; The science of the munchies

Raising doubts about mammograms

One of the largest and longest-running studies of mammograms ever conducted has determined that the screening tests do not improve a woman’s chances for surviving breast cancer. The findings, which run counter to widespread medical advice that women over 40 should undergo annual mammograms, also found that 20 percent of cancers detected via mammography and treated with often dangerous chemotherapy, surgery, or radiation therapies actually posed no threat to the women’s health. This study “will make women uncomfortable, and they should be uncomfortable,” University of North Carolina professor of medicine Russell Harris tells The New York Times. “The decision to have a mammogram should not be a slam dunk.” Researchers tracked roughly 90,000 Canadian women between the ages of 40 and 59 for 25 years. Some participants were randomly assigned to have both regular mammograms and breast exams by trained nurses, and others to have breast exams alone; their breast cancer death rates were the same. The study is bound to trigger further debate, since its results are at odds with American Cancer Society data suggesting that mammograms help to reduce the death rate from breast cancer by at least 15 percent for women in their 40s and by at least 20 percent for older women.

Extinction in a flash

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The mass extinction that wiped out more than 90 percent of life on Earth 252 million years ago appears to have occurred in the geological equivalent of a blink of an eye. A new study has found that the Permian extinction took only about 60,000 years, making it 10 times faster than previously thought. MIT geochemist Seth Burgess tells ScienceDaily.com that the great die-off happened “fast enough to destabilize the biosphere before the majority of plant and animal life had time to adapt.” The researchers came to that conclusion by reanalyzing rock samples collected in Meishan, China, where rock formations contain evidence of different geologic eras. They determined that the oceans experienced a sharp uptick in carbon levels roughly 10,000 years prior to the Permian extinction—likely reflecting a massive influx of the gas into the atmosphere. This could have led to widespread ocean acidification and a life-killing increase in sea temperature of at least 18 degrees Fahrenheit. Armed with the new finding, researchers now plan to closely examine evidence of one possible cause of that cataclysm: huge volcanic eruptions in Siberia that released climate-changing gases.

Printing cells that work

Taking a cue from an ancient Chinese printing method, scientists have developed a new and highly efficient way of “printing” networks of live cells. The block-cell, or “BlocC,” printing technique allows cells to be precisely placed into almost any configuration. Scientists have generally relied on a version of ink-jet printing when laying down grids of cells for lab experiments, but the high speeds at which the nozzles spit out cells leave many damaged or dead. The new technique works by essentially mimicking Chinese woodblock printing. Researchers created stamps out of silicone and installed microscopic hooks at regularly spaced intervals along the sides of the stamps’ grooves. When cell-filled fluid is pushed through the stamps, the hooks snag individual cells as they pass. When the mold is pressed onto a surface and then lifted away, it leaves the cells in place in an exact pattern. “The major improvement is that cells printed by BlocC printing are alive—close to 100 percent viability,” researcher Lidong Qin of the Houston Methodist Research Institute tells LiveScience.com. Scientists say block-cell printing may make it much easier to re-create and study neural networks and other complicated cell systems.

The science of the munchies

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The munchies, the craving for food that is one of marijuana’s signal effects, are triggered by a heightened sense of smell. Researchers at the University of Bordeaux reached that conclusion after studying how THC, marijuana’s active ingredient, affects the brains of mice. The substance activates cannabinoid receptors and sharpens the animals’ ability to smell, neuroscientist Giovanni Marsicano tells NationalPost.com, indicating that “the impact of marijuana on olfaction might be determinant for its effect on food intake.” The researchers found that the same receptors are activated in starving mice, suggesting that THC tricks the brain into feeling hungry by mimicking sensations that occur when it’s deprived of food. Mice that had been injected with THC sniffed—and kept on sniffing—banana and almond oils, while regular mice lost interest after a short while. The THC-dosed mice also ate more when given the chance. University of Calgary neuroscientist Jaideep Bains said that if the mechanism occurs in humans, it could open the way to drugs that fight obesity by interfering with the cannabinoid system. “If you are eating a lot, perhaps that olfactory system is in overdrive,” he says.

-

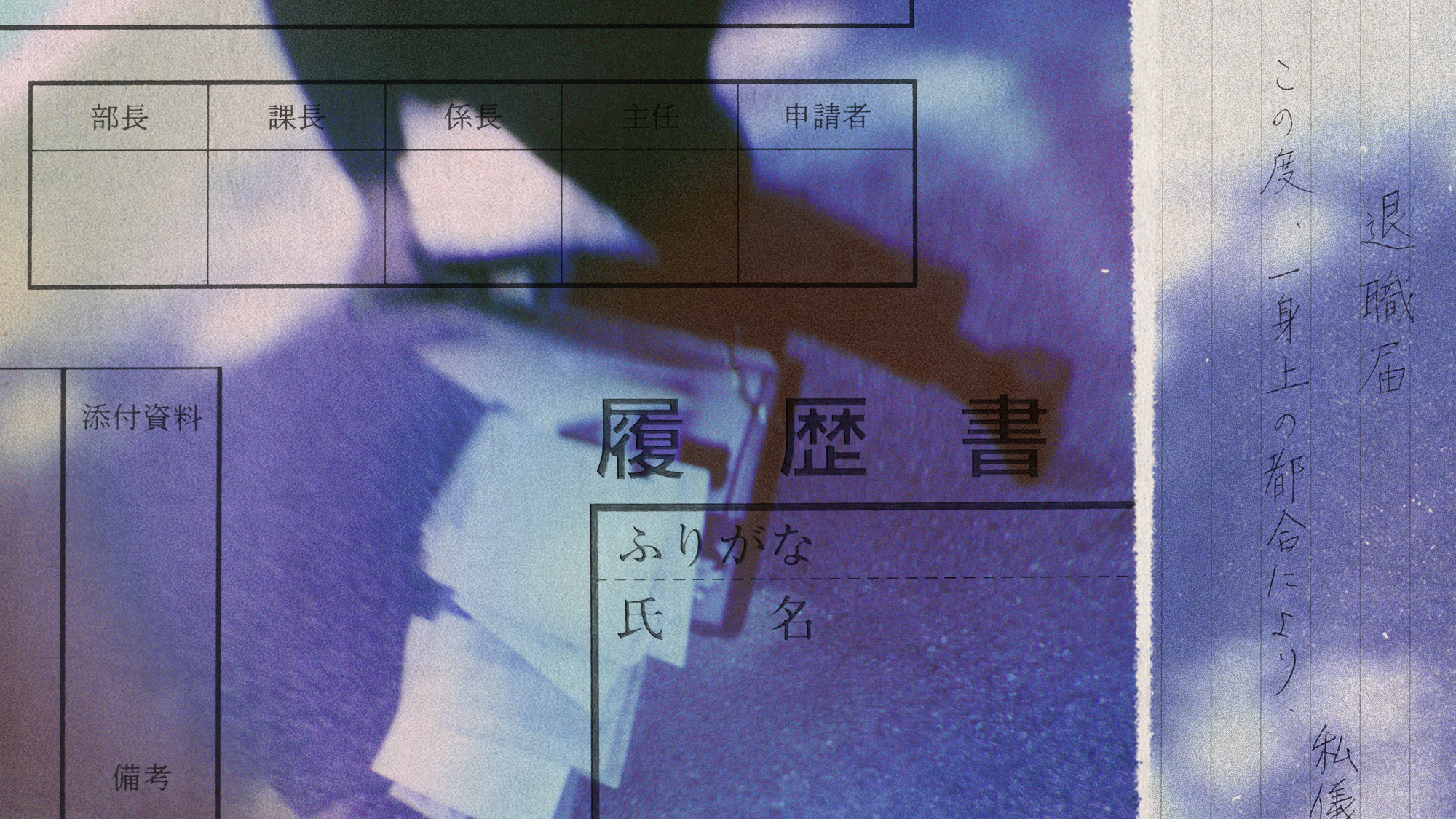

Why quitting your job is so difficult in Japan

Why quitting your job is so difficult in JapanUnder the Radar Reluctance to change job and rise of ‘proxy quitters’ is a reaction to Japan’s ‘rigid’ labour market – but there are signs of change

-

Gavin Newsom and Dr. Oz feud over fraud allegations

Gavin Newsom and Dr. Oz feud over fraud allegationsIn the Spotlight Newsom called Oz’s behavior ‘baseless and racist’

-

‘Admin night’: the TikTok trend turning paperwork into a party

‘Admin night’: the TikTok trend turning paperwork into a partyThe Explainer Grab your friends and make a night of tackling the most boring tasks

-

5 recent breakthroughs in biology

5 recent breakthroughs in biologyIn depth From ancient bacteria, to modern cures, to future research

-

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkiller

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkillerUnder the radar The process could be a solution to plastic pollution

-

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.Under the radar Humans may already have the genetic mechanism necessary

-

Is the world losing scientific innovation?

Is the world losing scientific innovation?Today's big question New research seems to be less exciting

-

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves baby

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves babyspeed read KJ Muldoon was healed from a rare genetic condition

-

Humans heal much slower than other mammals

Humans heal much slower than other mammalsSpeed Read Slower healing may have been an evolutionary trade-off when we shed fur for sweat glands

-

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brain

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brainSpeed Read Researchers have created the 'largest and most detailed wiring diagram of a mammalian brain to date,' said Nature

-

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'Speed Read A 'de-extinction' company has revived the species made popular by HBO's 'Game of Thrones'