Health & Science

How snakes gave humans good vision; Women’s gift for multitasking; Alzheimer’s genes identified; Invaders bred in the heartland

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How snakes gave humans good vision

Did primates develop superior vision so our ancestors could dodge dangerous snakes? That’s the implication of a new study that found that visual cells in monkeys’ brains are hardwired by evolution to react more sharply to images of snakes than to other stimuli. Researchers inserted electrodes into the brains of two macaque monkeys, aiming for the pulvinar, a cluster of neurons that is thought to control reflexive head and eye movement. Though the monkeys had never encountered snakes, their pulvinar neurons fired more rapidly and more often when the animals were shown images of coiled and elongated snakes than they did at the sight of geometric shapes or the faces and hands of monkeys. Evolutionary biologist Lynne Isbell of the University of California, Davis, says this suggests that the extraordinary visual acuity of some primates—including early Homo sapiens—developed primarily to keep them from being eaten. “They were actually prey,” Isbell tells the Los Angeles Times. “Snakes lie in wait. They don’t move very much, so it’s crucial to see them before they see us and to avoid them.” Primates that evolved in environments without poisonous snakes, such as the lemurs of Madagascar, have the poorest eyesight in the primate world.

Women’s gift for multitasking

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Busy women who juggle home and career often claim to be better at multitasking than men, and now there’s evidence to support them. After administering several tests to 120 men and 120 women, British psychologists concluded that men have more trouble juggling priorities—and are slower and less organized than women when switching between them. The researchers found that men and women were equally adept at completing two tasks on a computer when they could tackle them one at a time, but men’s performance slowed more substantially—by 77 percent compared with 69 percent for women—when they were forced to switch rapidly between the tasks. In another experiment, participants were given eight minutes to locate restaurants on a map, do simple math problems, answer the phone, and decide how to search for a lost key in a field. Particularly in the lost-key challenge, women outperformed men, who were more impulsive and failed to think through their search. University of Hertfordshire psychologist Keith Laws tells BBC.com that the study suggests that “in a stressed and complex situation, women are more able to stop and think about what’s going on in front of them.”

Alzheimer’s genes identified

The largest genetic analysis of Alzheimer’s disease ever conducted has linked 11 new genes to the disorder, opening promising new areas for research. “Each gene we implicate in the disease process adds new knowledge to our understanding,” Boston University geneticist Lindsay Farrer tells ScienceDaily.com. The study, a collaborative effort by four research consortia in the U.S. and Europe, examined the DNA of more than 74,000 older volunteers, some with Alzheimer’s and some without, across 15 countries. Researchers were especially intrigued to have found a link between Alzheimer’s and a region of the genome that is known to regulate the body’s immune system, and that has previously been associated with two other neuro-degenerative diseases: multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease. Farrer says the findings advance the prospect of gene therapies to fight Alzheimer’s. “Ultimately these approaches may be more effective in halting the disease,” he says, “since genes are expressed long before clinical symptoms appear and brain damage occurs.”

Invaders bred in the heartland

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Scientists have confirmed for the first time that Asian carp are breeding in the Great Lakes watershed—a bad sign for native fish whose habitats could be taken over by the invasive species. A bone chemistry analysis showed that four grass carp caught last year in Ohio’s Sandusky River, which flows into Lake Erie, had been spawned there. The findings suggest that many rivers in the watershed have the length and current needed by the grass carp and its voracious Asian cousins, the bighead and silver carp, to keep their eggs drifting long enough to hatch. “It’s bad news,” federal fisheries biologist Duane Chapman tells the Associated Press. “It would have been a lot easier to control these fish if they’d been limited in the number of places where they could spawn.” The Asian carp species were imported decades ago to restrict algae growth in sewage treatment lagoons, but they escaped into the wild, where they consume huge quantities of plankton and wreak havoc on the native aquatic food chain. The invaders have already established themselves in the Mississippi River basin, and the Obama administration has spent $200 million to keep them out of the Great Lakes, where they threaten a $7 billion annual fishing industry.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

5 recent breakthroughs in biology

5 recent breakthroughs in biologyIn depth From ancient bacteria, to modern cures, to future research

-

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkiller

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkillerUnder the radar The process could be a solution to plastic pollution

-

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.Under the radar Humans may already have the genetic mechanism necessary

-

Is the world losing scientific innovation?

Is the world losing scientific innovation?Today's big question New research seems to be less exciting

-

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves baby

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves babyspeed read KJ Muldoon was healed from a rare genetic condition

-

Humans heal much slower than other mammals

Humans heal much slower than other mammalsSpeed Read Slower healing may have been an evolutionary trade-off when we shed fur for sweat glands

-

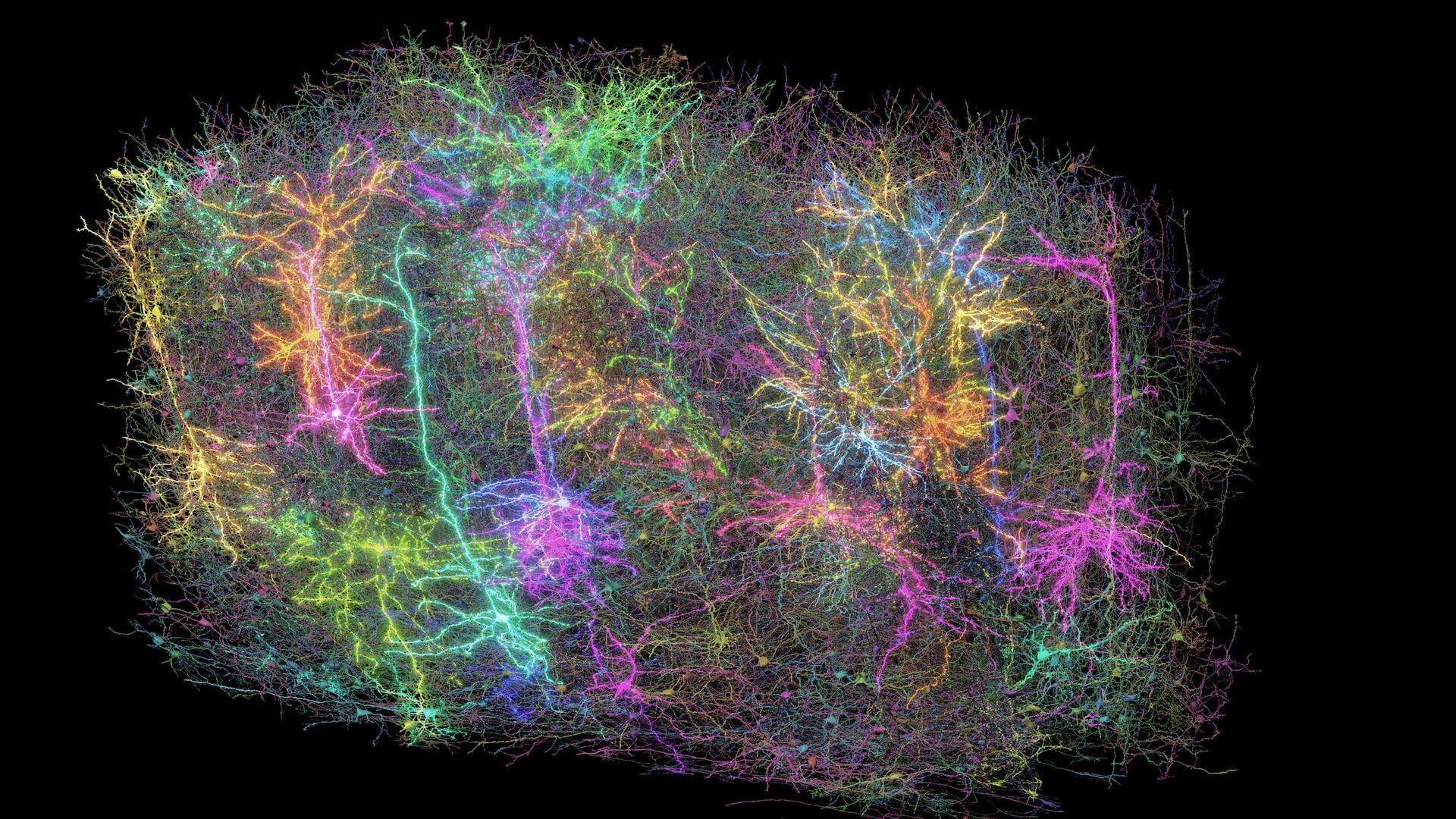

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brain

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brainSpeed Read Researchers have created the 'largest and most detailed wiring diagram of a mammalian brain to date,' said Nature

-

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'Speed Read A 'de-extinction' company has revived the species made popular by HBO's 'Game of Thrones'