Health & Science

A vaccine to prevent malaria; Global warming’s shrinking effect; Why TV is bad for tots; The pill’s effect on husband choice

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A vaccine to prevent malaria

For the first time, an experimental vaccine is providing immunity against malaria—a feat many scientists thought was impossible. Almost 800,000 people per year—mostly young children living in sub-Saharan Africa—die after being bitten by mosquitoes carrying malaria parasites. Millions more are left debilitated by the disease, which has plagued mankind for thousands of years. The new vaccine is only about 50 percent effective at preventing malaria, but the disease is such a “huge problem for the poorest of the poor” that even that imperfect result is “a really big deal,” Seth Berkley, CEO of the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization, tells Agence France-Presse. The vaccine is the first ever to protect against a parasite. Unlike viruses, parasites constantly change shape, making them hard for the immune system to defend against. Even after 25 years of research, “we still have a ways to go” to make the malaria vaccine as reliable as viral vaccines, which makers usually don’t distribute until they’re 90 percent successful, says Tsiri Agbenyega, head of malaria research at Komfo-Anokye Hospital in Ghana. He says researchers hope to improve the new drug “as we go along.”

Global warming’s shrinking effect

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Climate change is making plants and animals smaller, causing possibly serious disruptions to the food chain, a new study says. Researchers examined recent data on the changing sizes of 85 species and found that 45 percent have been steadily shrinking from generation to generation. Lab experiments show that rising CO2 levels in the atmosphere make ocean water more acidic, which causes the mass of plankton, corals, and mollusks to decrease. Each degree of warming has been found to decrease the size of marine life by as much as 22 percent. In theory, at least, plants—which use CO2 for fuel—should be growing bigger as more carbon dioxide enters the atmosphere. But they, too, are shrinking, likely because of droughts caused by climate change. Scientists fear that as certain types of flora and fauna diminish, the creatures that eat them will have to work much harder to get enough food—reducing human food sources. “I don’t think that organisms will shrink to the degree that you’ll walk outside and see that trees are suddenly half the size that they used to be,” University of Alabama researcher Jennifer Sheridan tells The New York Times. But the shrinking is noticeable, she says, and over time could have major consequences.

Why TV is bad for tots

For children under the age of 2, there’s no such thing as educational programming. That’s the finding of a new report by the American Academy of Pediatrics, which says parents should avoid letting kids that young watch any shows on TV—or on iPads, smartphones, or computers. Before the age of 2, children don’t understand what’s happening on-screen, but the noise and colors distract them from playing and interacting. That can lead to developmental delays, since “the more language that comes in—from real people—the more language the child understands and produces later on,” Temple University psychologist Kathryn Hirsh-Pasek tells The New York Times. Many previous studies have urged parents to limit tube time, but “clearly, no one is listening,” says pediatrician Ari Brown. Studies have found that 12-month-olds in the U.S. spend between one and two hours daily in front of a screen, and that as many as 60 percent of households keep TVs on all day. Even if kids aren’t actively watching, researchers say, exposure to such “secondhand TV” prevents them from engaging with adults or concentrating fully on their own play.

The pill’s effect on husband choice

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Women who take birth control pills are more likely to feel sexually frustrated with their partners than women who don’t, a new study says. But those same pill users are also more likely to describe their significant others as “caring and reliable,” as well as good fathers, Craig Roberts, a psychologist at the University of Stirling in the U.K., tells BBCNews.com. Roberts and his colleagues surveyed 2,500 mothers about their relationships with their children’s fathers. They found that those who were taking hormonal contraceptives when they met their mates stayed with them longer and were less likely to separate than women not on the pill. But they were also much more likely to report having lackluster sex lives. Previous studies have shown that when women are ovulating, they tend to be more attracted to handsome, hypermasculine men—who may be more fertile and produce healthier offspring, but who are also more likely to stray. When they’re not ovulating—the state the pill’s hormones promote—women seem to shift their preference “away from cads in favor of dads,” Roberts says. As a result, they choose men who are less physically exciting to them, but more committed to family life.

-

The Week contest: AI bellyaching

The Week contest: AI bellyachingPuzzles and Quizzes

-

Political cartoons for February 18

Political cartoons for February 18Cartoons Wednesday’s political cartoons include the DOW, human replacement, and more

-

The best music tours to book in 2026

The best music tours to book in 2026The Week Recommends Must-see live shows to catch this year from Lily Allen to Florence + The Machine

-

5 recent breakthroughs in biology

5 recent breakthroughs in biologyIn depth From ancient bacteria, to modern cures, to future research

-

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkiller

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkillerUnder the radar The process could be a solution to plastic pollution

-

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.Under the radar Humans may already have the genetic mechanism necessary

-

Is the world losing scientific innovation?

Is the world losing scientific innovation?Today's big question New research seems to be less exciting

-

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves baby

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves babyspeed read KJ Muldoon was healed from a rare genetic condition

-

Humans heal much slower than other mammals

Humans heal much slower than other mammalsSpeed Read Slower healing may have been an evolutionary trade-off when we shed fur for sweat glands

-

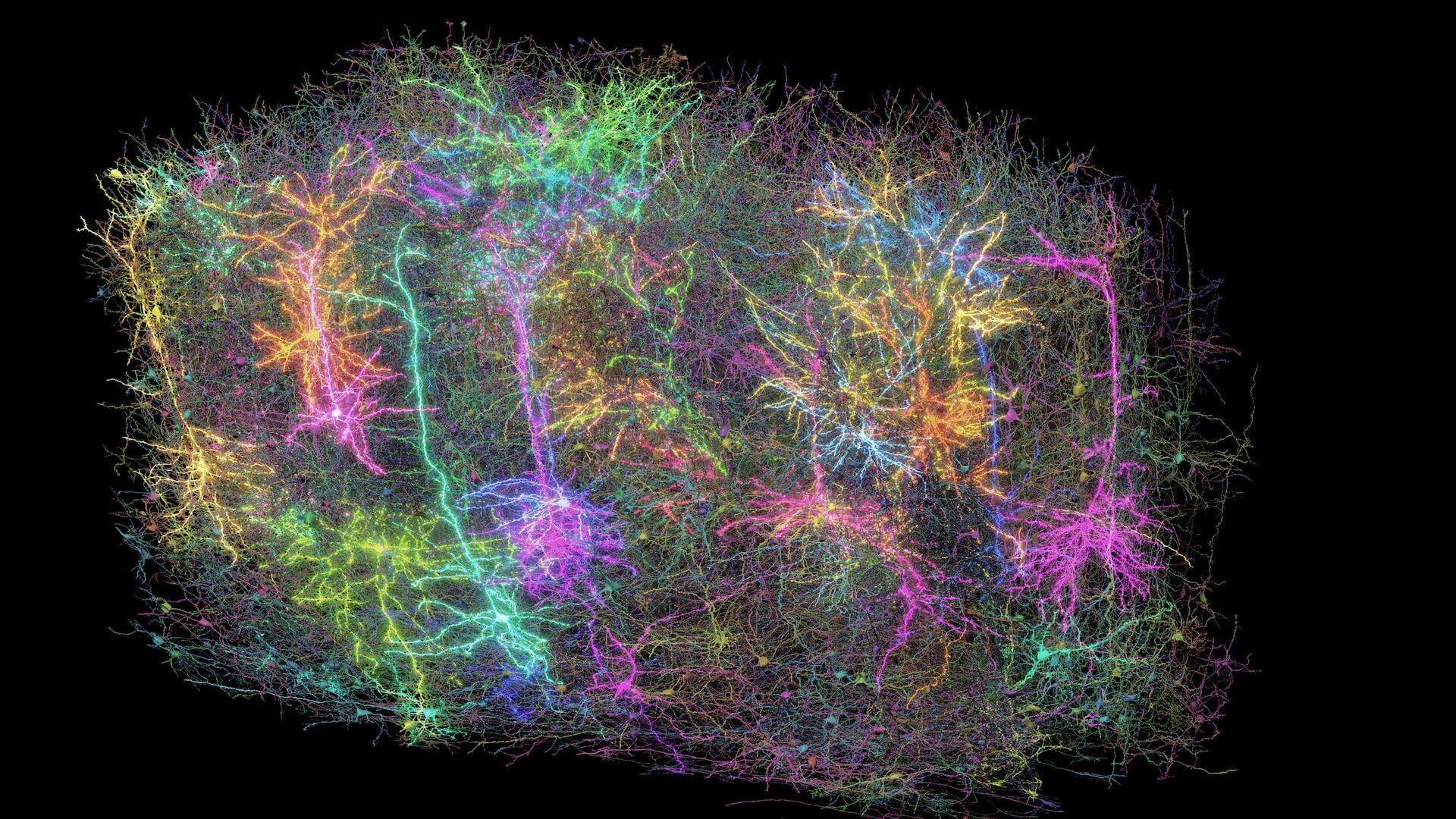

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brain

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brainSpeed Read Researchers have created the 'largest and most detailed wiring diagram of a mammalian brain to date,' said Nature

-

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'Speed Read A 'de-extinction' company has revived the species made popular by HBO's 'Game of Thrones'