France's unaccountable, incestuous, sexually exploitive political culture

As illustrated by the case of Dominique Strauss-Kahn

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This week marked the beginning of the trial of Dominique Strauss-Kahn and other characters on charges of "aggravated pimping" in France. In the United States, Strauss-Kahn is surely most notorious for the 2011 case in which he was accused by a hotel maid of attempted rape. (The charges were dropped after the French politician reached a settlement with the maid.) But there have been plenty of other allegations of sexual misbehavior against Strauss-Kahn over the years, including this latest set of charges, which revolve around allegations that Strauss-Kahn helped provide sex workers for a prostitution ring.

Now, I am often asked why, as a Frenchman, I seem more interested in writing on and identifying with American political life than that of my own native France. The case of Dominique Strauss-Kahn, a former French minister of finance, managing director of the International Monetary Fund, and leading candidate for the presidency of France, helps answer that question, by offering an excellent illustration of the hugely problematic issues I have with French political life.

France's lack of accountability. The French language literally does not have a word for "accountability." The word is usually translated as "responsabilité," which also carries the meaning of "liability," "competence," and "responsibility." The idea of accountability, as such — that one should face social consequences for reprehensible actions regardless of mitigating circumstances — has much less truck in Latin cultures than in Anglo ones.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

America is the land of second chances, but it only gives second chances after you suffer a hard fall. A second chance is a second chance: to give a second chance is to admit that someone had a first chance and blew it. By contrast, the French political system will most often pretend that the depredations of the powerful just haven't happened (the two leading conservative candidates for president right now are Nicolas Sarkozy, who failed in his previous presidential run, and Alain Juppé, who has a rap sheet for corruption). And when someone finally gets their comeuppance, the French will never grant them a second chance again.

The incest of the elites. In every country in the world, there is a tiny political-business-media elite that spends way too much time engaged in navel-gazing and daisy-chaining. The question is, how much does that tiny elite shield itself from the rest of the world? And in particular, how much does the media — which is part of the elite — protect the rest of the elite from accountability?

America used to have a "code of silence" around politicians' foibles. Franklin Roosevelt's polio and John F. Kennedy's extramarital dalliances were kept from the public by this implicit code of silence. And to this day, whenever an American politician commits a sexual indiscretion, we are treated to the predictable lament from the same quarter that a politician's personal life should not disqualify them from public office. But the fact that the same code of silence that shielded Kennedy's adultery also shielded his mob ties should make us rethink this position. The problem with this lack of transparency is that the media appoint themselves as guardians of what the public ought to know; and given that the media are never without conflicts of interest, this guardianship quickly becomes corrupt.

In the case of Strauss-Kahn, his libertine "lifestyle" was something that "everyone knew" in the small world of the French political elite. And yet, in part because of France's stringent privacy laws (which, of course, are written by politicians), and in part because of the more incestuous character of French media, they were never reported to the wider public. Even when credible allegations of rape were brought forward, they were surrounded by a cone of silence.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

If what happened in that hotel room in New York had happened in France, it would never have been reported.

For all of the many problems in American political culture, it's impossible to imagine an American Dominique Strauss-Kahn getting away with this sort of behavior for as long as he did. (Well, almost impossible.)

The link between sexual license and exploitation. Another reason why French media rarely reports on politicians' sex lives is because of a shared feeling in the French upper class that there's really nothing wrong with sexual license. Libertinage, adultery, open marriages, and the like are just shrugged off.

As the left understands when it comes to economics, the rhetoric of liberation can too often mask the reality of exploitation. The stubborn fact that men and women generally differ in sexual preferences and in assertiveness means that an ethic of "anything goes" will too often make formal consent a mere fig leaf for the exploitation of the weak by the strong. If consent can be murky in the case of a college hookup, if the power differential between a middle manager and a secretary makes a breach of decorum shade into harassment, then what are we to call rich, connected, powerful politicians preying on young women?

In France, we cling to the myth of the joyous libertinage, the merry orgy where everyone enjoys good liberating fun. But as Strauss-Kahn's long list of allegations makes clear, the reality is often far darker, and far murkier. Just like Jean-Paul Sartre before him, the standard-bearer of the modern French left was not striking a blow for liberation, he was exploiting young, often poor, often minority women.

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes, The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places. He lives in Paris with his beloved wife and daughter.

-

Political cartoons for February 12

Political cartoons for February 12Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include a Pam Bondi performance, Ghislaine Maxwell on tour, and ICE detention facilities

-

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ return

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ returnThe Week Recommends Carrie Cracknell’s revival at the Old Vic ‘grips like a thriller’

-

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ film

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ filmThe Week Recommends Akinola Davies Jr’s touching and ‘tender’ tale of two brothers in 1990s Nigeria

-

A peek inside Europe’s luxury new sleeper bus

A peek inside Europe’s luxury new sleeper busThe Week Recommends Overnight service with stops across Switzerland and the Netherlands promises a comfortable no-fly adventure

-

A long weekend in Zürich

A long weekend in ZürichThe Week Recommends The vibrant Swiss city is far more than just a banking hub

-

Late night hosts lightly try to square the GOP's Liz Cheney purge with its avowed hatred of 'cancel culture'

Late night hosts lightly try to square the GOP's Liz Cheney purge with its avowed hatred of 'cancel culture'Speed Read

-

Late night hosts survey the creative ways America is encouraging COVID-19 vaccinations, cure 'Foxitis'

Late night hosts survey the creative ways America is encouraging COVID-19 vaccinations, cure 'Foxitis'Speed Read

-

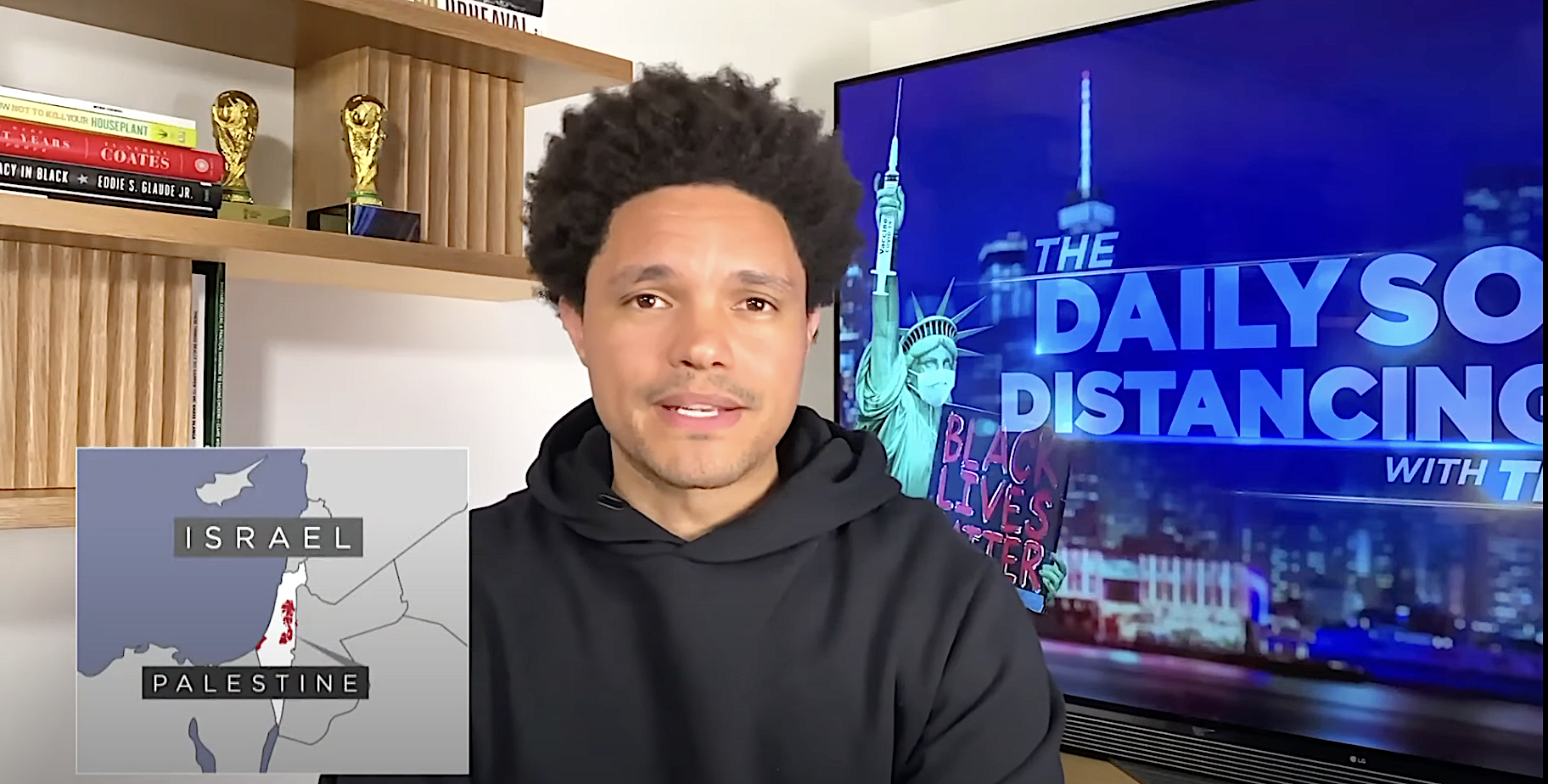

The Daily Show's Trevor Noah carefully steps through the Israel-Palestine minefield to an 'honest question'

The Daily Show's Trevor Noah carefully steps through the Israel-Palestine minefield to an 'honest question'Speed Read

-

Late night hosts roast Medina Spirit's juicing scandal, 'cancel culture,' and Trump calling a horse a 'junky'

Late night hosts roast Medina Spirit's juicing scandal, 'cancel culture,' and Trump calling a horse a 'junky'Speed Read

-

John Oliver tries to explain Black hair to fellow white people

John Oliver tries to explain Black hair to fellow white peopleSpeed Read

-

Late night hosts explain the Trump GOP's Liz Cheney purge, mock Caitlyn Jenner's hangar pains

Late night hosts explain the Trump GOP's Liz Cheney purge, mock Caitlyn Jenner's hangar painsSpeed Read