How can America and China avoid war? Start with North Korea.

Here's the deal America should forge with China — before there's a crisis

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In a recent column for The Week, I talked about what I consider to be the most pressing long-term foreign policy challenge facing the United States — to whit: avoiding an undesired and mutually-catastrophic war with a rising China. But I neglected to open the question of how that might be achieved. That's because the question is a difficult one to answer.

The trouble an existing, hegemonic power has in responding to the rise of a rival is that both accommodative and restrictive actions can lead to greater friction. For example, if the United States were to strengthen its military ties with Vietnam, this could be viewed in China as an effort to encircle it, leading China to counter with alliances of its own or by raising the move's cost to Vietnam. It could thereby provoke the very crisis it was intended to deter. On the other hand, if the United States moved from a policy of ambiguity on Taiwan to a clear declaration that we would not go to war to defend the island, this would likely be viewed as a weak retreat by Beijing, and prompt further testing on other points — or, even more likely, prompt our own allies (such as Japan) to question our resolve, and take independent actions that China would interpret provocatively. Once again, an attempt to avoid conflict could trigger conflict.

Moreover, we have to consider not only the impact of our policies on China, but the impact these policies have on ourselves, and the prospect of political blowback that could derail the most well-intentioned initiatives. To some degree, as a report from Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard notes, we've already observed this dynamic:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

[I]n 2013, Xi Jinping elevated the concept of "a new type of great power relationship" as a centerpiece of his diplomacy towards the U.S. Xi argued it was time to liberate the bilateral relationship from "a cold war mentality" (lengzhan siwei 冷战思维) and the politics of "a zero sum game" (linghe youxi 零和游戏). While disagreements inevitably arose over the definition of Chinese and American "core interests" (hexin liyi 核心利益). the U.S. administration initially welcomed the proposal. But this concept soon fell victim to a deeply partisan debate within the United States on the administration "conceding strategic and moral parity to China" and has since disappeared from the public language of the administration. [Belfer Center]

For all of these reasons, the most important guides to policy for those looking to avoid what Graham Allison calls a "Thucydides trap" are regular communication and a determination to avoid hasty decision making. If nothing else, that offers the hope of avoiding precipitous escalation when the inevitable crises do come up. But within that context, it's worth looking for opportunities to lay the groundwork for substantive cooperation that could bear larger fruit down the line — for the "win-win" situations that President Xi Jinxing called for.

The most promising example of such an opportunity lies on the Korean Peninsula.

It's not inconceivable that one day North Korean brinksmanship could spark a war. It's also possible that the North Korean regime could collapse catastrophically, leading to a necessary intervention both for humanitarian reasons and to protect South Korea. Nor can it be ruled out that a future American President would take preemptive military action against North Korea as we did in Iraq and as we have contemplated doing against North Korea in the past.

In current U.S. war planning, the assumption is that China would remain neutral in the event of war, both because of the potential cost to China and because it lacks the capability to prevail against the United States. But any such conflict would unquestionably be perceived as enormously threatening in Beijing, and would likely set China on a more determined course of confrontation in the future, with an aim to removing America from the Western Pacific. The time to defuse potential consequences for the U.S.-China relationship is now, before a crisis erupts.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Now consider what the effect might be of conducting frank, bilateral discussions with China about the future of the peninsula. These need not be, indeed likely should not be, public discussions, if for no other reason than both sides of the DMZ would receive it poorly for being left out. But the goal would be to make it clear that, in the context of a peaceful reunification of North and South, America would be comfortable with a Korea that was free of both nuclear weapons and American bases. A freely reunified and denuclearized Korea would not be a base for future American encirclement of China.

China would have little reason to trust American intentions after having observed the post-Cold War expansion of NATO into states that were once part of the Soviet Union. But the advantage of undertaking such conversations now, when the situation on the peninsula is relatively stable, is precisely that there is little risk for either party in coming to an understanding in principle. In the event of a crisis, each side would have the basis from prior conversations to know our stated aims, and to measure our actions against them. In that way, our behavior in a future crisis could lead to mutual confidence rather than escalation.

The conclusion of the nuclear agreement with Iran proves that it is possible for Washington to conduct diplomacy in the face of enormous domestic resistance when it is determined to do so. And the involvement of China in those negotiations provides a precedent for working cooperatively on difficult nuclear issues. In the best case, such conversations could actually make a contribution to resolving a major foreign policy problem. But at a minimum, our policymakers at the highest level would have a concrete opportunity to understand each side's true core interests better, in an area where those core interests, properly understood, align pretty well.

If we can't achieve constructive but realistic results in a forum like that, what are the odds that we will when our interests diverge more sharply?

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

A peek inside Europe’s luxury new sleeper bus

A peek inside Europe’s luxury new sleeper busThe Week Recommends Overnight service with stops across Switzerland and the Netherlands promises a comfortable no-fly adventure

-

A long weekend in Zürich

A long weekend in ZürichThe Week Recommends The vibrant Swiss city is far more than just a banking hub

-

Late night hosts lightly try to square the GOP's Liz Cheney purge with its avowed hatred of 'cancel culture'

Late night hosts lightly try to square the GOP's Liz Cheney purge with its avowed hatred of 'cancel culture'Speed Read

-

Late night hosts survey the creative ways America is encouraging COVID-19 vaccinations, cure 'Foxitis'

Late night hosts survey the creative ways America is encouraging COVID-19 vaccinations, cure 'Foxitis'Speed Read

-

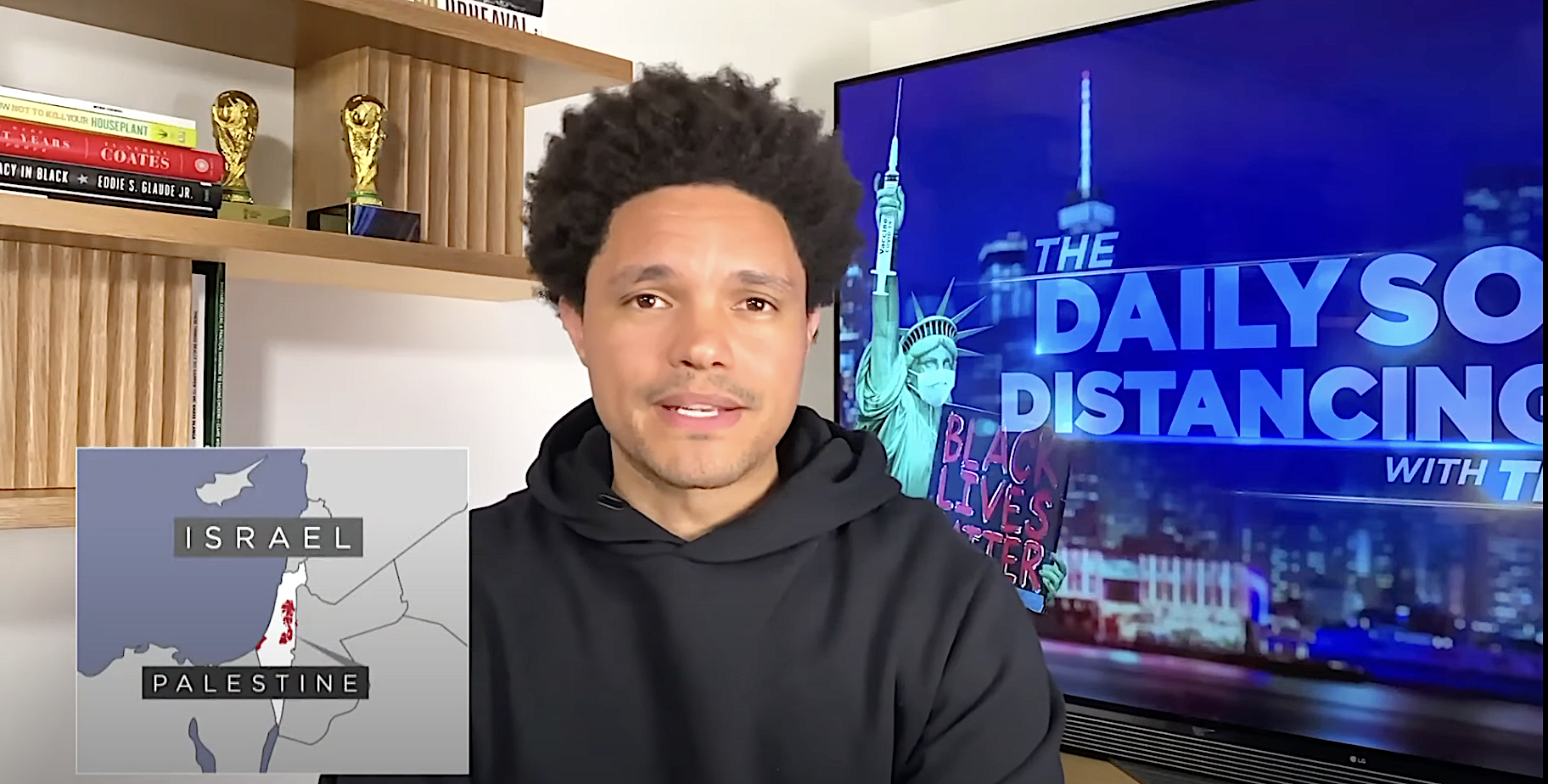

The Daily Show's Trevor Noah carefully steps through the Israel-Palestine minefield to an 'honest question'

The Daily Show's Trevor Noah carefully steps through the Israel-Palestine minefield to an 'honest question'Speed Read

-

Late night hosts roast Medina Spirit's juicing scandal, 'cancel culture,' and Trump calling a horse a 'junky'

Late night hosts roast Medina Spirit's juicing scandal, 'cancel culture,' and Trump calling a horse a 'junky'Speed Read

-

John Oliver tries to explain Black hair to fellow white people

John Oliver tries to explain Black hair to fellow white peopleSpeed Read

-

Late night hosts explain the Trump GOP's Liz Cheney purge, mock Caitlyn Jenner's hangar pains

Late night hosts explain the Trump GOP's Liz Cheney purge, mock Caitlyn Jenner's hangar painsSpeed Read