Here's the big economic point that all the Brexit pundits miss

Is trade really Britain's problem?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"To Brexit or not to Brexit?" But is that the question?

On June 23, a national referendum in Great Britain will decide whether the country breaks off its relationship with the European Union, and the pro-Brexit forces got a big boost this past weekend when the Mayor of London joined their cause.

Now, Britain has always been "semidetached" from the EU: It doesn't use the euro and it's not answerable to the supranational governance structure like full EU members are. But its relationship does impose certain rules on Britain when it comes to allowing people from other EU states to work in its borders and what government benefits they receive.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In particular, though, the relationship structures trade between Great Britain and the Continent, and a lot of observers are worried a Brexit would upend that. "More than 45 percent of British exports in goods go to the European Union, while less than 17 percent of EU exports go to Britain," The New York Times reported. "Even a minor disruption in Britain’s free-trade arrangement with the European Union would be costly, and if Britain votes to leave, Brussels will exact a price, in what could be a long and difficult negotiation, for the maintenance of a free-trade deal."

Unfortunately, this bit of conventional wisdom misses the key to Britain's trade problems.

Very crudely speaking, there are two big things to be concerned with when it comes to international trade.

The first is supply, or what you could call capacity. That's how much productive stuff an economy can do: how many workers, factories, computers, etc it has. But it's also how well it can do it: how productive or efficient the economy is, and how much unit of output per unit of input it can get. That's a matter of technology, of education, of innovation, of business models and so forth. Freer trade helps, since it vastly expands the number of people working to improve any given thing. If someone across the world invents a better mousetrap, you can buy it from them!

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This might be something Great Britain should be worried about. The amount of economic output a British worker produces by working one hour has grown for decades, but then slowed around 2000 and flatlined after 2008. So maybe Great Britain should be worried about keeping trade with Europe as free as possible.

But then there's the second concern when it comes to trade: demand. That's what actually makes use of supply. It's possible to have lots of workers and factories and computers and such, but for them to not be doing anything. In fact, that's what a recession is: lots of productive resources in an economy sitting idle because demand is too low.

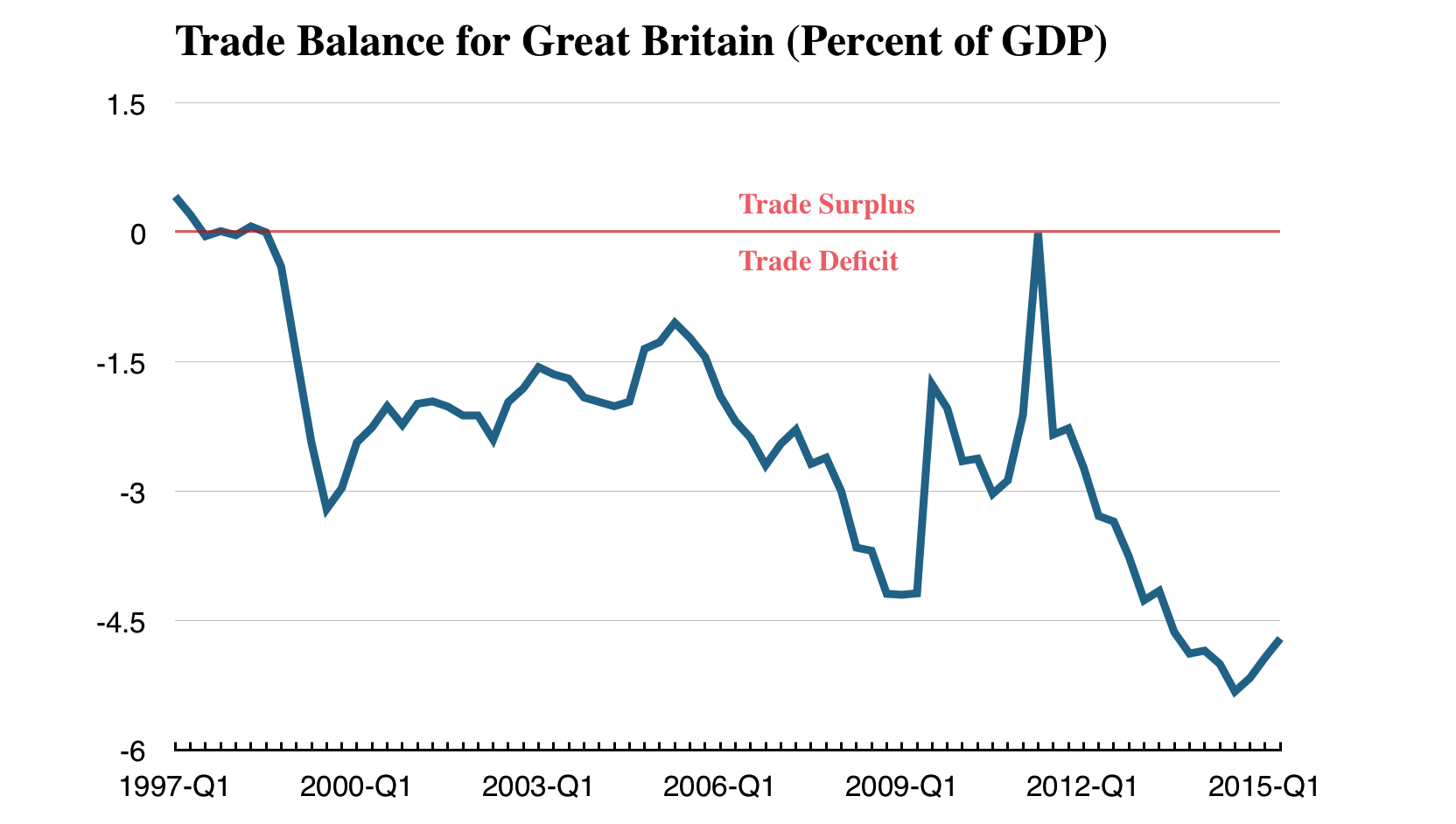

Trade matters here because when a country has a trade deficit — when it's importing more stuff from other countries than it's importing to them — that means that some of the demand it's generating isn't going to create jobs and utilize capacity in its own economy. Instead, that demand is going to create jobs and utilize capacity in someone else's economy. And Great Britain has been in a trade deficit for a while now:

On balance, it seems like the trade deficit's effect on demand is what Great Britain should be worried about. There are a lot of signs that they still aren't generating enough demand to make full use of its own capacity, much less anyone else's. The unemployment rate shot up to 8 percent with the Great Recession, and has fallen to 5.3 percent since. Though, unlike America, Britain did manage to keep its labor force participation stable during the Great Recession.

But Britain's unemployment rate is still above the 4.6 percent mark it hit in the mid-2000s, and around a third of the unemployed have been looking for work for a year or more. Employment among young people also plummeted in 2008 and hasn't fully recovered. And overall the OECD thinks the country still isn't back to full capacity utilization (Figure 14B).

But probably the key signs are that wage growth for British workers is still flat or negative (Figure 11B) and inflation is still rock bottom. Both of those measures would be rising if demand had met or exceeded supply and capacity.

Now, Great Britain's trade deficit certainly isn't the whole problem here. But, by draining some of the country's demand to other shores, it's not helping.

Ironically, financial market nervousness over the Brexit dispute is driving down the value of the pound, which should help to close the trade deficit by making British exports less expensive. But with the global economic slump driving everyone's currencies down — and given that the Bank of England has set interest rates near zero since the Great Recession — there's probably not a whole lot more Britain can do to close its trade deficit with currency adjustments.

That means it falls to the fiscal policy of the British government to supply the necessary demand. But for most of the recovery it's been moving in exactly the wrong direction, cutting both its deficits and its overall spending as a percentage of the economy. Only within the last two years did British fiscal policy stop being a net drag on its economy (Figure 4B), and it still has a ways to go before repairs are finished.

All told, Great Britain is probably better off remaining in the European Union. Being able to maintain freer trade with the Continent certainly doesn't hurt.

But the main point is that Britain's big challenges lie elsewhere. "To Brexit or not to Brexit" isn't really the question.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.