Thomas Becket: murder and the making of a saint

The Guardian says this show ‘makes the art of the Middle Ages come alive’

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“If you thought medieval religious art was all clasped hands and uplifted eyes”, this gory, “brilliant” show will put you right, said Jonathan Jones in The Guardian. On 29 December 1170, four knights entered Canterbury Cathedral and slaughtered its archbishop, Thomas Becket – “a flamboyant, charismatic politician” who had once been King Henry II’s closest ally, but had become a “thorn in his side” as archbishop because he consistently championed the authority of the Church over that of the English Crown. When Becket excommunicated several bishops loyal to the king, it enraged Henry. “Who will rid me of this turbulent priest?”, he supposedly thundered.

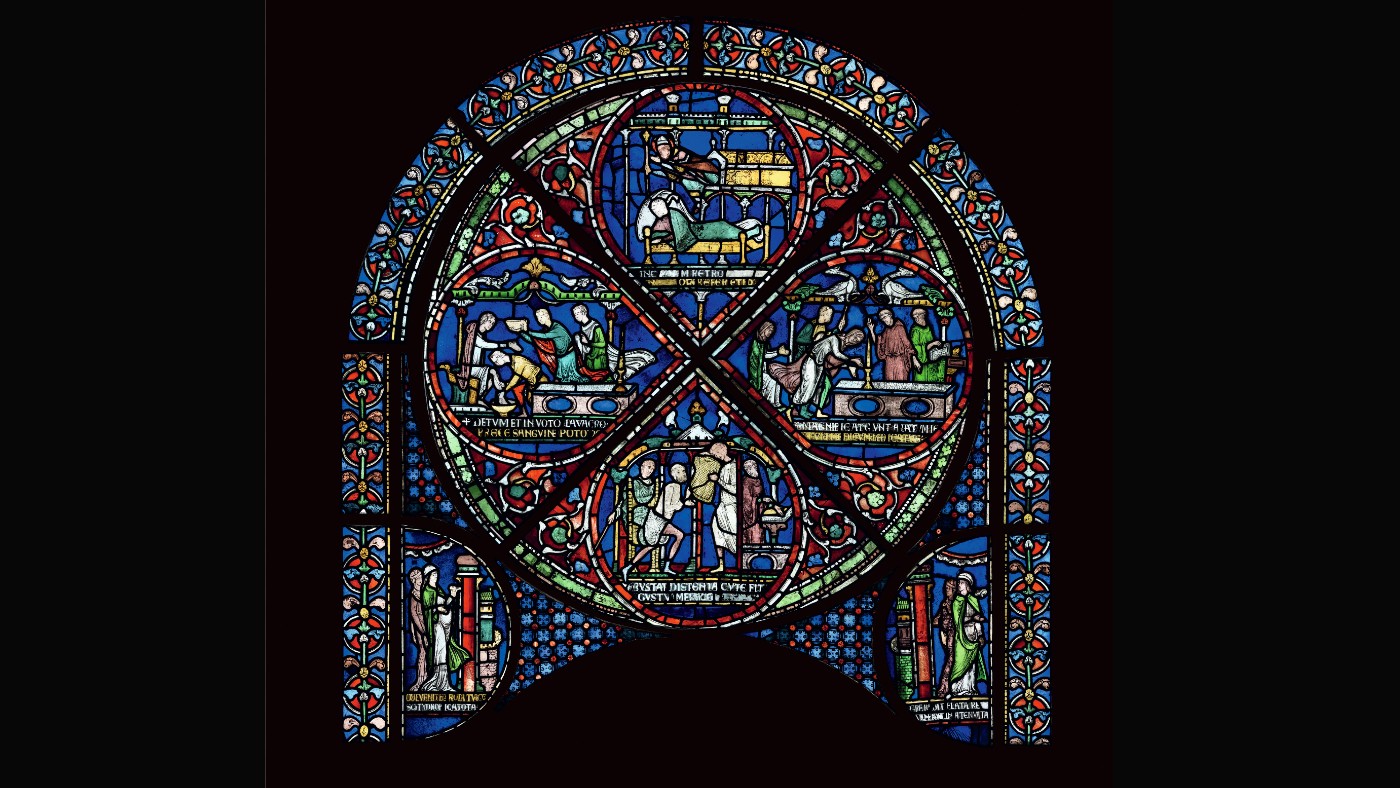

Whether or not the king had meant to order it, the murder shocked the rest of Catholic Europe. Henry’s name went down in infamy, while Becket was canonised just three years later, his stand against state authority becoming a byword for righteous defiance. Becket’s life and legacy are now the subject of a major exhibition at the British Museum, which brings together more than 100 extraordinary objects, from jewellery and prayer books to relics and even stained glass windows – many featuring “startling death scenes”. This show “makes the art of the Middle Ages come alive”.

This “fascinating” exhibition shows how Becket became a “religious phenomenon”, said Tim Stanley in The Daily Telegraph. Soon after his murder, we learn, people flocked to the cathedral to collect his blood; one man “rushed some home” and gave it to his wife, who was instantly cured of an illness. It was the first of many miracles attributed to the slain archbishop, whose reputation would spread far and wide, along with his sanctified body parts; we even see a probable fragment of Becket’s skull that was preserved as a relic.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

As the show explains, such gruesome artefacts made their way around Europe, their geographical reach suggesting that the Middle Ages was a more cosmopolitan era than generally assumed. Indeed, far from being an insular society, Norman England belonged to “an empire that stretched from the Scottish border to the Pyrénées”, while London, Becket’s birthplace, thronged with trade from as far afield as China. Nor was it as technologically backward as generally believed: a psalter displayed here is adorned with illustrations of the “state-of-the-art” 12th century water pumping system employed at Canterbury Cathedral.

The exhibits are spectacular, said Rachel Campbell-Johnston in The Times. We see “elaborate gold croziers and episcopal rings”; “gilded caskets” that once contained “grisly relics”; and “gorily dramatic” depictions of Becket’s murder. Most spellbinding of all are a number of huge stained- glass windows on loan from Canterbury Cathedral itself, their “kaleidoscopic panes” depicting the “bizarre assortment” of miracles Becket supposedly performed: a “dramatic crimson nosebleed” cures a monk of his illnesses, while a man who has been “blinded and castrated” has his eyes and testicles restored to him.

Yet the humbler exhibits are the most evocative. We see “pieces of old bone”; a “blob of red wax” that survives as one of the only objects we know he touched; and a “tiny illumination” believed to be the only portrait of Becket made in his lifetime. It adds up to a “marvellous, multifaceted” exhibition which imaginatively “resurrects not just a solitary figure, but an entire age of faith”.

British Museum, London WC1 (020-7323 8299, britishmuseum.org). Until 22 August

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

Greenland’s capital becomes ground zero for the country’s diplomatic straits

Greenland’s capital becomes ground zero for the country’s diplomatic straitsIN THE SPOTLIGHT A flurry of new consular activity in Nuuk shows how important Greenland has become to Europeans’ anxiety about American imperialism

-

‘This is something that happens all too often’

‘This is something that happens all too often’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Friendship: 'bromance' comedy starring Paul Rudd and Tim Robinson

Friendship: 'bromance' comedy starring Paul Rudd and Tim RobinsonThe Week Recommends 'Lampooning and embracing' middle-aged male loneliness, this film is 'enjoyable and funny'

-

The Count of Monte Cristo review: 'indecently spectacular' adaptation

The Count of Monte Cristo review: 'indecently spectacular' adaptationThe Week Recommends Dumas's classic 19th-century novel is once again given new life in this 'fast-moving' film

-

Death of England: Closing Time review – 'bold, brash reflection on racism'

Death of England: Closing Time review – 'bold, brash reflection on racism'The Week Recommends The final part of this trilogy deftly explores rising political tensions across the country

-

Sing Sing review: prison drama bursts with 'charm, energy and optimism'

Sing Sing review: prison drama bursts with 'charm, energy and optimism'The Week Recommends Colman Domingo plays a real-life prisoner in a performance likely to be an Oscars shoo-in

-

Kaos review: comic retelling of Greek mythology starring Jeff Goldblum

Kaos review: comic retelling of Greek mythology starring Jeff GoldblumThe Week Recommends The new series captures audiences as it 'never takes itself too seriously'

-

Blink Twice review: a 'stylish and savage' black comedy thriller

Blink Twice review: a 'stylish and savage' black comedy thrillerThe Week Recommends Channing Tatum and Naomi Ackie stun in this film on the hedonistic rich directed by Zoë Kravitz

-

Shifters review: 'beautiful' new romantic comedy offers 'bittersweet tenderness'

Shifters review: 'beautiful' new romantic comedy offers 'bittersweet tenderness'The Week Recommends The 'inventive, emotionally astute writing' leaves audiences gripped throughout

-

How to do F1: British Grand Prix 2025

How to do F1: British Grand Prix 2025The Week Recommends One of the biggest events of the motorsports calendar is back and better than ever