How 'personhood' works as a legal defense of nature

Will giving the environment the rights of a human encourage conservation efforts?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In June, a municipality in the Brazilian Amazon called Guajara-Mirim successfully designated the Komi Memem River, known as the Laje in non-Indigenous maps, and its tributaries as "living entities with rights, ranging from maintaining their natural flow to having the forest around them protected," per The Associated Press. It is now the first of hundreds of rivers in the region to be granted "personhood status."

In terms of environmental conservation, legal personhood involves giving nature similar rights as humans so as to protect the planet from destruction. The designation is growing in popularity, especially as the climate crisis worsens.

What is legal personhood in this context?

Giving nature "legal personhood" involves the granting of "basic legal rights," which can "help protect it from threats like deforestation, biodiversity loss, chemicals pollution, and climate change," said Politico. Viewing nature as a person rather than "as an object" that "serves us" might put society in the mindset to want to protect it, Eduardo Salazar, a lawyer that helped grant legal rights to Mar Menor, a large saltwater lagoon in southeastern Spain, told the outlet.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In the case of the Amazon region, legal personhood serves to limit deforestation and its impact on the Indigenous Wari' people. "The loggers entered and divided up the Indigenous land," Gilmar Oro Nao, vice president of the Oro Wari' association, told the AP. "They threaten food security. Our relatives have nowhere to fish, the Brazil nut trees were cut down. Today, they have nowhere to draw their survival from." Globally, Indigenous communities have advocated for legal personhood for various natural areas.

The "Rights of Nature" movement started approximately 50 years ago in the U.S., and has since spread to countries like Ecuador, which was the first the enshrine the Rights of Nature into its constitution in 2008; India, where the Madras High Court in Tamil Nadu state recently ruled that nature should receive the "corresponding rights, duties, and liabilities of a living person"; and Bangladesh, which in 2019 gave all of its rivers legal protection. The popularity of the method has grown in part thanks to the worsening climate crisis and the resulting need for environmental protection. "Nature shouldn't be treated as just our property, but instead should have basic fundamental rights, just as humans have rights and just as, for better or worse, corporations have rights," environmental lawyer Grant Wilson told CBC.

How does this work legally?

Essentially, because natural entities like lakes, rivers and forests are entitled to the legal protections of humans, "companies could be taken to court for damaging the river or its ecosystem," Juanpablo Ramirez-Franco reported for NPR. "There's this shortcoming of our current legal system in which we sort of allow nature to perpetually decline," said Wilson, the environmental lawyer. "We're never actually regenerating nature to health, but sort of allowing it to exist in this grey area between existence and collapse."

"Rights of nature makes a fundamental shift from human-focused law, where human rights are all about the rights of human beings, to the rights of nature, which also overcomes this fundamental binary in law between persons and things," said Dr. Marc De Leeuw, senior lecturer at the Law and Justice department of the University of New South Wales in Sydney.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"We're rapidly coming to a place where, without this kind of new system of environmental law — that we're all kind of done," said Thomas Linzey, a senior attorney at the Center for Democratic and Environmental Rights, per NPR.

Is it actually helpful?

While some believe legal personhood for nature gives the public more of an incentive to protect the environment, others believe it is "largely symbolic" and "doubt it can do much to help protect and restore ecosystems," per Politico. Critics argue that legal personhood gives "power to particular people" to determine what is good for a particular environment and it's not guaranteed that those in power will make the right decision, Michael Livermore, a law professor at the University of Virginia, told the outlet.

Property ownership becomes complicated under legal personhood, as well. Experts wonder whether treating nature as a human means that "no one will be able to own anything related to nature," including land and homes, according to Earth.org. "Without a notion of how to actually define the interests that are affected and how to compare them against each other, the idea of nature's rights is just extraordinarily indeterminate," Livermore said, per NPR.

Still, legal personhood could prove a powerful first step to "give us a tool to prosecute the worst offenders of environmental harms," Wilson remarked. "It comes from communities who have often directly been impacted by environmental pollution, degradation or climate change, and were disappointed by more conventional environmental law approaches which have often been ineffective," added the University of New South Wales' Dr. De Leeuw.

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

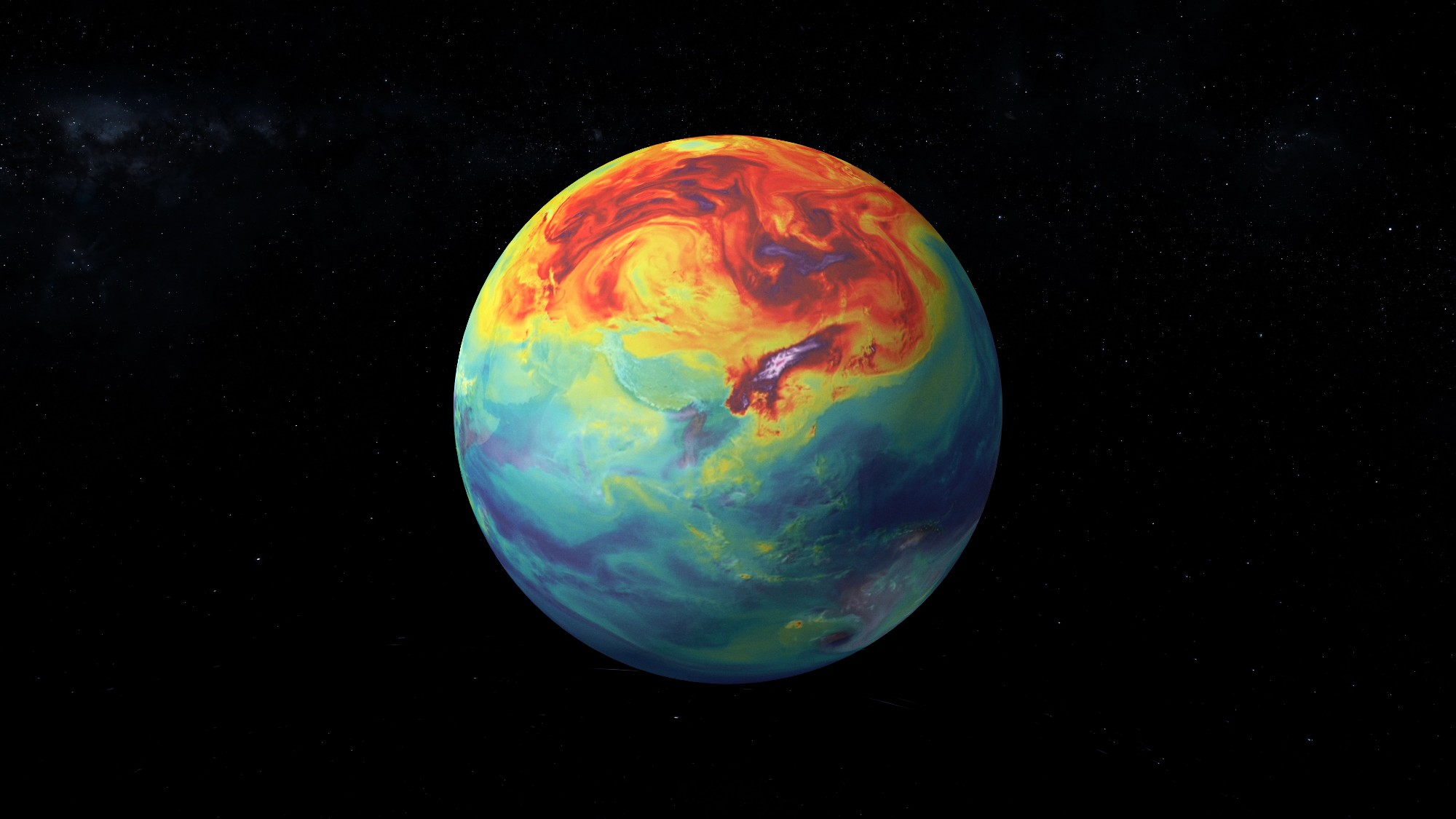

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

How climate change is affecting Christmas

How climate change is affecting ChristmasThe Explainer There may be a slim chance of future white Christmases

-

Why scientists are attempting nuclear fusion

Why scientists are attempting nuclear fusionThe Explainer Harnessing the reaction that powers the stars could offer a potentially unlimited source of carbon-free energy, and the race is hotting up

-

Canyons under the Antarctic have deep impacts

Canyons under the Antarctic have deep impactsUnder the radar Submarine canyons could be affecting the climate more than previously thought

-

NASA is moving away from tracking climate change

NASA is moving away from tracking climate changeThe Explainer Climate missions could be going dark

-

What would happen to Earth if humans went extinct?

What would happen to Earth if humans went extinct?The Explainer Human extinction could potentially give rise to new species and climates

-

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkiller

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkillerUnder the radar The process could be a solution to plastic pollution

-

A zombie volcano is coming back to life, but there is no need to worry just yet

A zombie volcano is coming back to life, but there is no need to worry just yetUnder the radar Uturuncu's seismic activity is the result of a hydrothermal system

-

'Bioelectric bacteria on steroids' could aid in pollutant cleanup and energy renewal

'Bioelectric bacteria on steroids' could aid in pollutant cleanup and energy renewalUnder the radar The new species is sparking hope for environmental efforts