Food and drink trends of 2024

From the best way to cook rice to the secrets to a perfect toastie

- A bug-friendly eatery in north London

- Italy's risotto crisis

- The return of the devilled egg

- How to paillard

- Britain's bread wars

- The best supermarket veggie soup

- A taste of Scotland in north London

- Secrets of the perfect toastie

- Where to eat in... Barcelona

- Lessons from the golden arches

- The secrets of forced rhubarb

- Dave Myers and the Hairy Biker effect

- The chef making history in Fitzrovia

- How to cook perfect rice

- The skill behind The Taste of Things

- The ageing of the restaurant scene

- How to beat the coffee snobs

- When sliced white is just right

- Britain's bagel boom

- Starting out with an air fryer

- Novel uses for olive oil

- Ripping up the rulebook

- 'Greek-style' vs. real Greek

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A bug-friendly eatery in north London

With "jaunty yellow branding" and the promise of "small plates", Yum Bug, a new restaurant in Finsbury Park, north London, could be "any trendy rollout", said Ed Cumming in The Telegraph. But in fact, it is – as its website reveals – "Britain's first permanent edible insect restaurant". Co-founder Leo Taylor spent much of his childhood in Asia, where he became aware of traditions of eating insects. He teamed up with entomologist Aaron Thomas, and the pair have since developed a "meat" made from crickets, which features across Yum Bug's menu. The "brave pioneers" who go there might eat Welsh rarebit made with minced cricket, burrata served with whole roasted crickets, or pulled cricket tacos. And for pudding, there's pear cricket crumble. Undoubtedly, the environmental case for eating insects is strong: unlike "carbon-intensive" cows, pigs or sheep, invertebrates are cheap, plentiful and sustainable. Moreover, as they're "less cerebral" than livestock, fewer people have ethical objections to eating them. Yet as Taylor acknowledges, there remains a perception problem: many people think the very idea of eating insects is disgusting. Whether Yum Bug can change this remains to be seen, but the early signs are promising. When Taylor and Thomas trialled their cricket meat at a pop-up before Christmas, they "ended up with 1,000 people on the waiting list".

Italy's risotto crisis

I realise it's probably "peak middle class" to fret about the future of "posh rice", said Rachel Cooke in The Observer. But I am nonetheless concerned about Italy's "risotto crisis". Risotto can only be made with varieties such as arborio and carnaroli, which are super-absorbent yet retain their texture over a slow cook. And these are exclusively grown in the Po Valley, a floodplain in northern Italy just south of the Alps. Once, farmers there struggled "to keep the water away". Now, thanks to climate change, things are topsy-turvy. "In 2022, the worst drought in 200 years struck the Po, the river that feeds the system of canals that irrigates the paddy fields." Rice production dropped by more than 30%. Last year, it was again lower than usual. Varieties such as carnaroli are difficult to grow at the best of times; if droughts keep occurring, they could become unviable. And since there are no obvious other places to grow them, that would effectively mean the end of risotto. What a "grave development" that would be: for Italians, for Europeans, and perhaps especially "for we British, who came a bit late to risotto, and have only just started truly to get the hang of it".

The return of the devilled egg

Hearty pies, prawn cocktails, tinned fish: retro foods have been making a comeback, said Rosanna Dodds in the FT. And the latest to join them is the devilled egg, a staple of "sad '70s buffets" which has recently acquired a "new groove". Jazzed-up versions of this classic dish – traditionally made by scooping the yolk out of a hard-boiled egg, mixing it with paprika, mayonnaise and "some sort of hot sauce", and then piping the mixture back in – have become common on restaurant menus. At Camille in Borough Market, London, the eggs are served with slices of smoked eel; Peckham restaurant Levan adds an "umami bomb" of miso; the Seaside Boarding House in Dorset has developed a ramen version. If making them at home, chef Tom Brown (who serves them with caviar at his new Shoreditch restaurant, Pearly Queen) says it's best to keep things "as retro as possible". Make sure, he says, to use a star-shaped piping nozzle, and don't stint on the spice.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How to paillard

The French word for a piece of meat that is pounded flat and then fried is "not a verb", said Sarit Packer and Itamar Srulovich in the Financial Times, "but we'd argue that it should be". To paillard, flatten the meat (which could be chicken breast, veal loin, beef or pork) with a mallet or rolling pin until it is "just shy of 1cm thick". Leave it for half an hour in a "simple but assertive marinade" – typically a good oil and something acidic – and then "scorch in a fiercely hot pan for a minute or two on each side". Because the meat is typically lean, a paillard demands "something a bit rich to go with it". One of our favourite accompaniments – which is particularly good with pork or veal – is an onion, lemon and walnut relish, which can be made while the meat is marinading.

Sweat a finely chopped onion in a pan with 50g of butter and the zest of a lemon until it's a deep golden brown. Add 50g of coarsely chopped walnuts, cook until they're nicely toasted, take off the heat and stir in the juice of a lemon, some finely chopped chives, a bit of salt and lots of pepper. Then simply spoon this over your meat once the meat is cooked.

Britain's bread wars

The cheapest loaf in my nearest supermarket costs 45p, said Rachel Dixon in The Guardian, while the cheapest in my local artisanal bakery costs £5. "Which of these facts riles you up?" For many people, the answer will be both. Some deplore the existence of ultra-processed sliced white; others see "bougie" sourdough loaves as the ultimate expression of middle-class smugness. But it's hardly surprising that "our most basic foodstuff" is divisive, for it has been ever thus. For most of British history, white bread (made with laboriously milled white flour) was the preserve of the rich, while inexpensive brown bread was eaten by the poor. This changed in the 1870s, with the invention of steel rollers: by ripping off the brown bran and oily germ from the wheat, they made it possible to produce white flour "in a flash". Soon, the bread hierarchy flipped: white bread became the worker's choice, while "healthy" brown bread became the posher option. Another "gamechanger" occurred in the 1960s, with the invention of the Chorleywood bread process (CBP): this allowed loaves to be produced quickly and cheaply in factories, and in so doing, killed off thousands of local bakeries. Nowadays, 80% of bread sold in Britain is made using CBP, though it requires more hard fats and chemicals to produce, leaving precious few options for those who want to "buy a decent loaf" but don't want to pay £5 for the privilege. So long as this remains the case, the "bread wars" will continue to rage.

The best supermarket veggie soup

"The problem with soup," said Hannah Evans in The Times, "is that the moments you crave it most tend to be when you don't have the time or energy to make it." That is why I love a chunky vegetable soup – it requires minimal chopping or stirring – but for times when even that seems too much, there are some decent shop-bought alternatives. Of those I tasted, the winner was Aldi's Soupreme Country Vegetable Soup. Aromatic and creamy, it was "reminiscent of something you'd eat in a National Trust cafe" after a long walk. Also very good was M&S's Chunky Country Vegetable Soup, which "needs a bit more seasoning", but is something I'd happily eat for lunch. New Covent Garden Vegetable Soup was "satisfying". But avoid Tesco's Garden Vegetable soup: it has a "sour, nose-wrinkling taste".

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

A taste of Scotland in north London

When Gregg Boyd first moved to London in his 20s, he couldn't believe how hard it was to find the "incredible produce" he'd grown used to while living in his native Scotland, said Marc Horne in The Times. This frustration led the Glaswegian, who was then working as an economist, to open a weekend market stall in the East End, where he sold haggis, neeps and tatties to some of the 200,000 or so Caledonians who live in the capital. His side hustle has now morphed into a full-time job: last month, Boyd opened Auld Hag: The Shoap in Islington – London's first-ever Scottish deli. Alongside freshly baked goods such as Glasgow morning rolls and Aberdeen butteries, it sells smoked fish from Arbroath, Highland venison, chocolate made in Glasgow and soft drinks made from Scottish-grown soft fruit. And already it has "become the toast of north London". Around 400 customers turned up on the very first day, and the shop soon ran out of Tennent's, Irn-Bru and tattie scones. "Some people had travelled from Kent and even further than that to get some stuff they hadn't had for a long time," said Boyd.

Secrets of the perfect toastie

"The UK is without doubt a nation of toastie lovers," said Silvana Franco in The Telegraph: more than 31 million of us admit to eating one a week. The question now is, how can this snack – a dish seemingly so "straightforward it barely feels worth thinking about" – be taken to the next level? What are the secrets of sarnie perfection? There are no hard and fast rules, but to "ensure enough ooze", I would aim for "a good 1cm in depth of coarsely grated cheese". I like double gloucester, but the variety isn't hugely important: pretty well any cheese that softens when warm works in a toastie. A really good melter such as mozzarella is terrific paired with something stronger, such as a vintage cheddar. And make sure to grate your own: pre-grated cheeses are usually coated with an anti-caking agent, which makes them grainy when they melt. For bread, white or spelt sourdough is best, though sliced white is acceptable. Extra flavourings depend on the cheese: a strong gruyère won't need more than a "smear of wholegrain mustard or a few slices of tomato"; milder cheeses work better with full-flavoured relishes or chutneys. Butter the outside of your sandwich, right up to the crusts, and then cook it in a heavy griddle or frying pan, which you've preheated to medium-high. As it cooks, press the toastie firmly down with a spatula. It's ready when the outside is brown and crunchy, and the cheese inside is gooey.

Where to eat in... Barcelona

Barcelona, where I've lived for most of my life, is a city with a huge and unexpectedly varied food scene, said chef Albert Adrià – brother of Ferran of El Bulli fame – in the Financial Times. The kebabs at Bismillah Kebabish in the Raval are really quite special, and it does the "softest shawarma bread". Also brilliant is Come, a Michelin-starred Mexican restaurant (make sure to order the suckling-pig tacos). For a casual vermouth and tapas, my "little secret" is Bodega del Vermut, not far from the cathedral: its interior is "one of the most beautiful and authentic corners in Barcelona". Also "special" is the Spanish-Japanese fusion food at Dos Palillos, next to the Museu d'Art Contemporani. For food shopping, I'd avoid the famous Boqueria market, which has gone downhill in recent years. Instead head for the less touristy Mercat de Santa Caterina, or the Mercat Sant Antoni, which is around the corner from my restaurant, Enigma.

Lessons from the golden arches

When you visit a foreign country, there's an assumption that the sophisticated thing to do is to immerse yourself in its local cuisine, said Flora Gill in The i Paper. By this logic, popping into a branch of McDonald's makes you an "uncultured simpleton". But I take issue with that idea – for while McDonald's may be "the perfect example of globalisation", its outposts vary considerably round the world, and I've found that you can learn a great deal about a country by seeking out its version of the golden arches. In

"overwhelmingly Hindu" India, for example, I couldn't get a beefburger. In Canada, I had my fries coated in a mix of gravy and cheese curds known as poutine. In Shanghai, I enjoyed a side of congee, or rice-based porridge, with my morning McMuffin. Some overseas McDonald's are even worth visiting for the "visuals alone" – check out, if you can, the spectacular art deco branch in Melbourne. So don't "turn your nose up at a quick visit to Maccies"; instead, treat it as a learning experience.

The secrets of forced rhubarb

When "flashes of pink" start appearing in greengrocers, it means that forced rhubarb season has arrived, said Rosanna Dodds in the FT. The season – which typically runs from January until the end of this month – is a joyous time for those who love this "exquisite" and traditional British delicacy. A "clandestine version of normal rhubarb", forced rhubarb is produced by growing rhubarb roots outside for two years and then transferring them into "warm, dark sheds" (alternatively, they can simply be covered with pots or buckets). The roots respond to the dark by growing more quickly – their way of seeking out the light – but because photosynthesis cannot occur, the plants produce very few leaves. As a result, explains Yorkshire rhubarb farmer Robert Tomlinson, "the sugars stay in the stick", creating a fruit that is "far more tender and sweeter" than its non-forced equivalent. Much like wild garlic, forced rhubarb is prized by chefs and foodies. "London's restaurants go crazy for it", and if you find it in your local shop, "prepare to pay a price". The sweetness of forced rhubarb makes it delicious in desserts (you can't go wrong with a crumble), but its "bright acidity" means it also pairs well with many savoury ingredients, especially fatty, oily proteins such as pork belly or mackerel.

Dave Myers and the Hairy Biker effect

The death last month of Dave Myers – one half of the Hairy Bikers – was a sad moment for those who enjoyed his TV shows and cookbooks. "But it wasn't just fans whose lives were touched by this pair of itinerant gastronomes," said Hannah Al-Othman in The Sunday Times. Myers and his co-host, Si King – with whom he "zipped across Britain on motorbikes", discovering the best restaurants, pubs and producers – had an immense impact on many of the businesses they featured. In 2021, they visited KC Caviar, a sustainable caviar producer near Selby in North Yorkshire. Myers described their caviar as "the best in the world", and according to owner John Addey, the company's website instantly went mad. "It was just like a machine printing orders, brmm, brmm, brmm," he recalls. A "similar frenzy" occurred last month, when an episode of The Hairy Bikers Go West featured Mr Thompson's Bakery in Ormskirk, Lancashire, which specialises in traditional gingerbread. "Within an hour of the show going out we'd had over a thousand orders," said owner Neil Thompson. For a small business like his, he added, gaining the Hairy Bikers' stamp of approval made an "immeasurable" difference.

The chef making history in Fitzrovia

Eighteen months ago, Adejoké Bakare was serving her West African cuisine to "hungry hipsters" in a "cramped pop-up" in south London's Brixton Village Market, said Nadia Cohen in The Times. Now, the 51-year-old has made history by becoming the first black woman in Britain to be awarded a Michelin star, for her Fitzrovia restaurant Chishuru. Bakare, known as Joké, grew up in northern Nigeria, where she learnt to cook from her grandmother. She moved to London in her late 20s, and worked for a property company while spending her weekends hosting supper clubs. In 2020, a friend alerted her to a culinary competition that offered its winner a residency in Brixton Village Market. Bakare entered (her friend had threatened to disown her if she didn't) and duly won. She opened her Fitzrovia restaurant only last September, with the help of a crowdfunding campaign. The dishes there are more "high-end" than at her pop-up, but are still inspired by the flavours of her childhood. Chishuru has become wildly popular – it's booked out months in advance – but some diners have complained that the prices are too high and the portions too small. Such criticisms, she said, come from a place of "internalised racism" – the idea that "African food should be piled high".

How to cook perfect rice

"Rice is one of those ingredients that people find the easiest thing in the world to cook or, frustratingly, the hardest," said Yotam Ottolenghi in The Guardian. Which of those it is will depend on many things – from the type of rice you're using (fibrous brown rice, for example, takes much longer than white) to the dimensions of your pan. Let's assume, though, that we're talking about cooking white basmati rice (or another long-grain white variety) in a pot and on a hob. If that's the case, there's one technique – known as the "boil-steam method" – which should work every time. Begin by rinsing the rice to get rid of its starchy coating, and then soak it for at least an hour. Once it's drained, use this simple ratio to work out how much water you need: one part rice to one-and-a-half parts water. Put the water and rice in a pot, bring to the boil, give it a quick stir, and then cover and turn the heat right down. After 12 minutes, take off the heat, and set aside, still covered, for five minutes. Then fluff with a fork.

The skill behind The Taste of Things

Reviewers of The Taste of Things – the new film starring Juliette Binoche, set in a 19th century French château – have marvelled at its lavishly detailed cooking scenes. The opening sequence in particular – 38 virtually dialogue-free minutes of chopping, stirring and measuring – has been singled out for praise. It's no accident that such scenes are convincing, said Sudi Pigott in The Daily Telegraph: they were made under the "expert" tutelage of one of the world's greatest chefs, Pierre Gagnaire. Tran Anh Hung, the film's director, spent many hours in the 73-year-old's three-Michelin-starred Paris restaurant, filming him making all the dishes cooked and eaten in the film and capturing his "precise techniques, embellishments and mannerisms". The clips were then studied by the actors. Once filming got under way, Gagnaire was on set to ensure that all the details were correct. He eschewed the "tricks" used by food stylists; everything, he said, was "done for real" – including preparing the giant stuffed vol-au-vent that appears in one of the most memorable scenes. It had to be made 15 times, each time looking "exactly the same". But the result of such meticulousness, he said, is a film that "will be remembered for ever".

The ageing of the restaurant scene

When I began writing about British food two decades ago, said Tim Hayward in the FT, it felt as if a "revolution" was taking place. The country's previously rather staid restaurant scene was becoming more experimental, and was increasingly being run by "cool young people". Yet that youthquake appears to be coming to an end. At the age of 60, said Hayward, I now often appear to be the "youngest person in the dining room" in many top restaurants. And the "person serving you or cooking your food can almost certainly not afford the experience you are expecting them to provide". Rarely has the "income-and attitude-chasm between server and served yawned so wide", and that could spell the end of Britain's "easy-going restaurant scene", and a return to dining out being the preserve of "the old and the elite".

How to beat the coffee snobs

There was a time when owning a French press (or, perhaps, a Bialetti stovetop moka pot) was the mark of a true coffee connoisseur, said Harry Wallop in The Times. But that won't cut it now. The pandemic pushed coffee snobbery to "new extremes", as people unable to buy coffee in cafés attempted to replicate their favourite brews at home. Some – mostly men – began to "invest a lot of time and money in buying posh kit". The really dedicated might have splashed out on a £4,160 La Marzocco Linea Mini espresso machine, which makes "coffee as good as in a Florentine café". Yet most experts say you really don't need to spend a lot to enjoy great coffee at home. The most important thing, said Howie Gill of roastery Grind, is the coffee: if you have "nice, freshly roasted coffee", you're already "95% of the way there". He recommends brewing it using a V60 – a simple funnel used to make "pour over" coffee that can cost as little as £6. This results, he said, in a "cleaner, more balanced-tasting cup" than with a French press. Another fairly inexpensive option is the AeroPress, an "ingenious" contraption that looks like a giant syringe, costs around £30 and "makes a great cup in 20 seconds".

When sliced white is just right

Nigella Lawson recently told an interviewer that there are times when only supermarket bread hits the spot. And, as usual, she was absolutely right, said Silvana Franco in The Telegraph. When it comes to a "proper bacon sarnie", for instance, nothing beats the "soft squash of sliced white". Thickly sliced white is also just the thing for a fish finger sandwich, ideally made with four or five fingers per butty, plus mayo, a dash of hot sauce and some gem lettuce. Because sliced white absorbs liquids so well, it's ideal for bread and butter pudding, summer pudding and French toast. And its uses don't end there. If you push de-crusted and buttered slices into muffin trays and bake them for around 12 minutes, you'll have the "world's easiest" tartlet cases.

Britain's bagel boom

Once, specialist bagel shops in Britain were confined to areas that have (or had) large Jewish populations, such as London's Brick Lane and Manchester's Prestwich, said Tomé Morrissy-Swan in The Daily Telegraph. But that's no longer the case. Since lockdown, Britain has been experiencing a "bagel boom", with the result that high-quality bagels can now be found all over the country. In the north of England, for instance, there's King Baby Bagels in Newcastle (renowned for its salted ham, pease pudding, dill pickles and mustard bagel), Chapter One Bar & Kitchen in Oldham, and the hugely popular Lincoln Bagel Co in Lincoln. Moving down the country, doughnut and bagel specialist The Steamhouse now has seven sites in the Midlands and the south of England, including one in Oxford. Traditional-with-a-twist bagel bakeries are also "popping up" in the capital, many inspired by New York's bagel culture. It's Bagels!, which opened in Primrose Hill in October, is owned by New Yorker Dan Martensen. He had "struggled to find the bagels of his youth" after moving to London in 2019. New York bagels, he said, are larger and less chewy and dense than London ones. His bakery is designed to resemble a "traditional Big Apple bagel shop" and offers fillings such as lox (smoked salmon) and "schmears" (flavoured cream cheeses). And they are already proving popular: on Sunday mornings, people queue for up to two hours to get them.

Starting out with an air fryer

If you got an air fryer for Christmas, and haven't used one before, it's worth taking time to get to know your machine, says Anna Berrill in The Guardian. While air fryers can be transformative for a home cook, they can be surprisingly frustrating to begin with. As they're not all "created equal", it really is a good idea to read the manual. Take time to test out cooking times, because some models are more ferocious than others. Don't assume (as many do) that your air fryer doesn't need pre-heating: in this respect, it's like a conventional oven. As for dishes to try out first, Poppy O'Toole, author of "The Actually Delicious Air Fryer Cookbook", recommends a whole roast chicken. It isn't too hard, and gives a good indication of an air fryer's capabilities. The "chicken stays incredibly moist yet still gets that crispy skin" everyone loves, she says.

Novel uses for olive oil

If you only ever use extra-virgin olive oil in savoury dishes, "you're missing a trick", says Sarah Rainey in The Times. For as well as being good for you, olive oil is extraordinarily versatile: it "makes the creamiest cheesecakes", the "fluffiest sponges", and even the most "deliciously drinkable" cocktails. Chefs have recently cottoned on to this "untapped potential", and are using it in ever more inventive ways. Fast becoming a "staple of modern menus" is olive-oil ice cream, which is renowned for its velvety consistency. Other chefs drizzle olive oil over fresh or poached fruit, or add it to mousses and truffles. Ferran Adrià, formerly of El Bulli (considered the world's best restaurant until it closed in 2011), suggests combining it with grated chocolate on bread for a "surprisingly tasty" snack. According to chef and food writer Ursula Ferrigno, the versatility of olive oil results from the fact it contains so many phenolic compounds, which act as flavour-enhancers. Cutting-edge mixologists now use olive oil to jazz up cocktails, and there are non-alcoholic options, too: try "adding it to your morning smoothie, blending it into coffee", or using it to enrich hot chocolate.

Ripping up the rulebook

High-end restaurants are going to "rip up the fine dining rule book" this year, said Restaurant magazine. In the industry, it is felt that tasting menus – for a long time the bedrock of top-end dining – are losing their appeal for diners. And so restaurants are starting to junk them, and are returning to à la carte menus. One restaurant that has already done so is 670 Grams in Birmingham, which recently replaced its seven-course tasting menu with a "more informal" sharing-style format. Others set to follow suit include Pidgin in London's Hackney and The Man Behind the Curtain in Leeds. Another trend to look for this year is "confrontational dining" – or food that in some cases literally "stares right back at you". At Fowl, a new pop-up "beak-to-feet" chicken shop in London's St James's, the signature dish is a pie of hearts, livers and cockscombs that has a "chicken's head emerging from the pastry". Meanwhile, the breaded and fried pheasant leg served at Manteca in Shoreditch comes with the foot still attached. Two recent trends from New York are also set to hit Britain this year. One is for "comforting" New York-style Italian dishes, such as lasagne, vodka tomato sauce and spaghetti meatballs; the other is for "smashed" burgers – burgers pressed into the griddle as they cook to create a "thinner, crispier" patty.

'Greek-style' vs. real Greek

The UK market for Greek and Greek-style yoghurts has boomed in recent years, but "let's clear one thing up", said Xanthe Clay in The Telegraph: the imitators are "not even close" to the real thing. Unlike the "authentic" stuff, Greek-style is really "just set milk", has a "fairly thin" texture, "can be made almost anywhere". Greek yoghurt, on the other hand, must be made in Greece, and has a "thicker, creamier" texture because it is strained to remove most of the whey. This requires more milk "to make the same amount", so it's more expensive. But while Greek-style yoghurts "are nice enough eaten with fruit", it's worth paying more for the "really seductive, rich creaminess" of the real deal, argued Clay, whose favourites include Fage Total and for a more budget-friendly option, Lidl's "luscious" Milbona Authentic Greek Yogurt, at £1.89 for 500g.

-

Political cartoons for February 3

Political cartoons for February 3Cartoons Tuesday’s political cartoons include empty seats, the worst of the worst of bunnies, and more

-

Trump’s Kennedy Center closure plan draws ire

Trump’s Kennedy Center closure plan draws ireSpeed Read Trump said he will close the center for two years for ‘renovations’

-

Trump's ‘weaponization czar’ demoted at DOJ

Trump's ‘weaponization czar’ demoted at DOJSpeed Read Ed Martin lost his title as assistant attorney general

-

Exploring Vilnius, the green-minded Lithuanian capital with endless festivals, vibrant history and a whole lot of pink soup

Exploring Vilnius, the green-minded Lithuanian capital with endless festivals, vibrant history and a whole lot of pink soupThe Week Recommends The city offers the best of a European capital

-

The best fan fiction that went mainstream

The best fan fiction that went mainstreamThe Week Recommends Fan fiction websites are a treasure trove of future darlings of publishing

-

The Beckhams: the feud dividing Britain

The Beckhams: the feud dividing BritainIn the Spotlight ‘Civil war’ between the Beckhams and their estranged son ‘resonates’ with families across the country

-

6 homes with incredible balconies

6 homes with incredible balconiesFeature Featuring a graceful terrace above the trees in Utah and a posh wraparound in New York City

-

The 8 best hospital dramas of all time

The 8 best hospital dramas of all timethe week recommends From wartime period pieces to of-the-moment procedurals, audiences never tire of watching doctors and nurses do their lifesaving thing

-

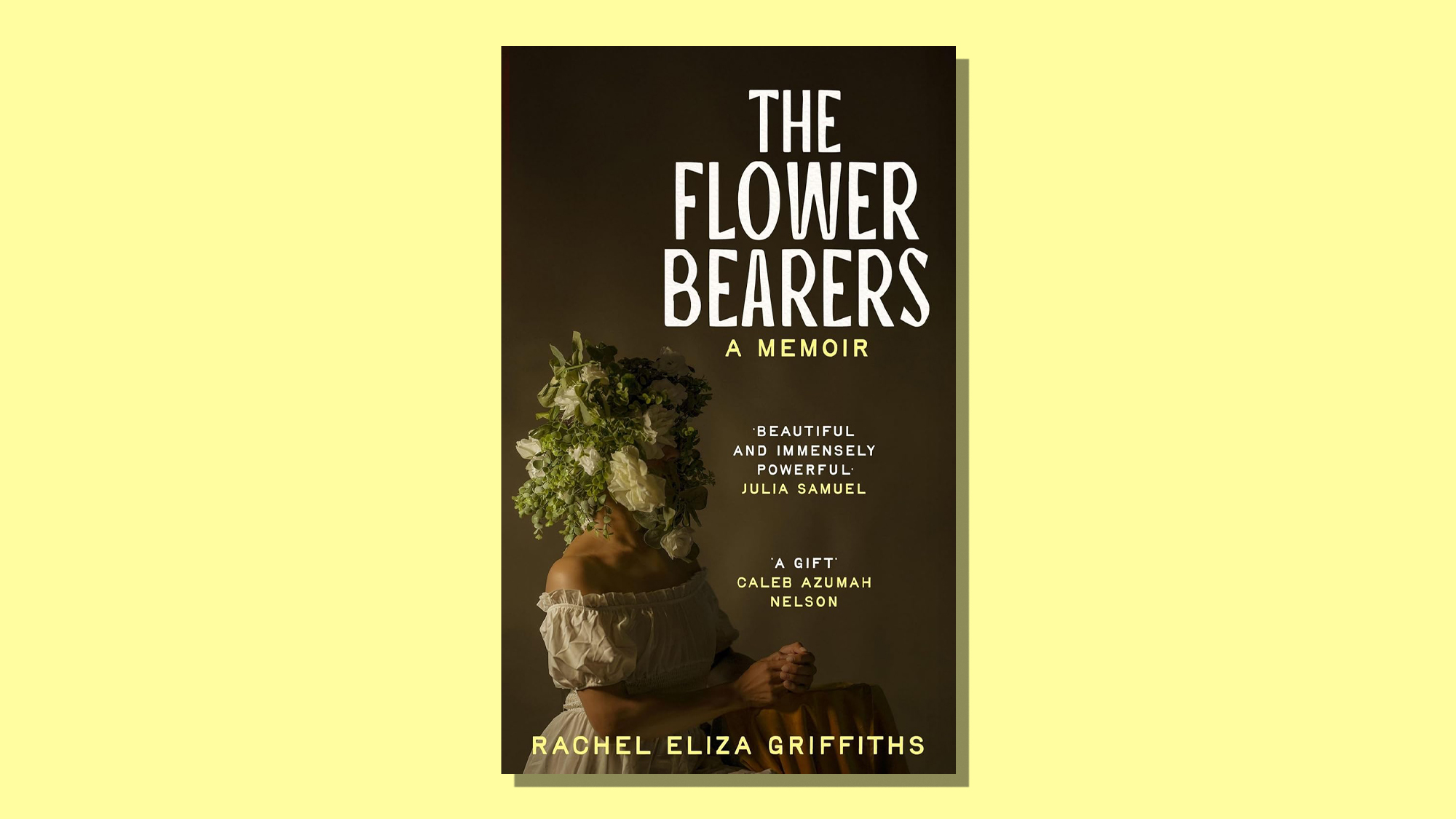

The Flower Bearers: a ‘visceral depiction of violence, loss and emotional destruction’

The Flower Bearers: a ‘visceral depiction of violence, loss and emotional destruction’The Week Recommends Rachel Eliza Griffiths’ ‘open wound of a memoir’ is also a powerful ‘love story’ and a ‘portrait of sisterhood’

-

Steal: ‘glossy’ Amazon Prime thriller starring Sophie Turner

Steal: ‘glossy’ Amazon Prime thriller starring Sophie TurnerThe Week Recommends The Game of Thrones alumna dazzles as a ‘disillusioned twentysomething’ whose life takes a dramatic turn during a financial heist

-

Anna Ancher: Painting Light – a ‘moving’ exhibition

Anna Ancher: Painting Light – a ‘moving’ exhibitionThe Week Recommends Dulwich Picture Gallery show celebrates the Danish artist’s ‘virtuosic handling of the shifting Nordic light’