Fact check: does mindfulness improve mental health?

Schools in England will be teaching the practice to children and teenagers in a major new trial

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Hundreds of children in England will be taught mindfulness techniques in one of the largest trials of its kind in the world, the government announced this month.

The study, running at 370 schools in the country until 2021, will see students learn relaxation techniques and breathing exercises to help improve their mental health and wellbeing.

Mindfulness is often touted as a tool to help people with a range of mental health conditions including anxiety and depression, but is there evidence it works? The Week takes a look at the existing research.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What exactly is mindfulness?

Mindfulness has roots in Buddhism and is a way of helping people manage their thoughts and feelings by paying attention to the present moment. This is typically done by focusing on breathing, bodily sensations and thoughts.

“[It] is not about getting rid of negative thoughts, it’s about learning to sit with and tolerate all of our experiences, including difficult experiences, with kindness and compassion towards ourselves,” Dr Clara Strauss, research lead at the Sussex Mindfulness Centre, told The Guardian.

Mindfulness can be learned and practiced in a variety of ways. Some choose to attend group or one-on-one sessions with a therapist, while others prefer to do so individually using online courses or mobile apps.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What do experts say?

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice), which provides evidence-based treatment guidelines to the NHS, recommends the practice as a way to prevent depression in people who have experienced several depressive episodes in the past.

However, Nice recommends against using mindfulness-based treatments for social anxiety.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), which combines cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) methods with mindfulness meditative practices, is routinely prescribed to people with recurrent depression.

MBCT “is a powerful intervention,” says consultant psychiatrist Dr Florian Ruths. “It isn’t fluffy or alternative. The MBCT course is based on solid scientific research”.

But experts caution that mindfulness is not a panacea. It requires commitment and practice to be effective and is not an appropriate treatment for all mental health conditions.

“Mindfulness isn’t the answer to everything, and it’s important that our enthusiasm doesn’t run ahead of the evidence,” says Professor Mark Williams, former director of the Oxford Mindfulness Centre, part of the University of Oxford’s department of psychiatry.

“There’s encouraging evidence for its use in health, education, prisons and workplaces, but it’s important to realise that research is still going on in all of these fields,” he adds.

Psychologists also warn that MBCT isn’t suitable for patients struggling with a drug or alcohol addiction. “Also, patients who are recently bereaved may find MBCT too overwhelming,” says Dr Christina Surawy, a clinical psychologist.

What does the research say?

Several studies have highlighted the benefits of different mindfulness-based therapies.

In 2015, a study comparing mindfulness to medication found that MBCT could be just as effective as antidepressants at preventing depression.

The two-year clinical trial at Oxford University involved 424 patients who had a history of depression and were taking antidepressants to prevent further relapses.

Half of the group received MBCT and were given support to stop taking medication, while the other half continued taking antidepressants for the duration of the trial.

By the end of the study, a similar proportion of people had relapsed in both groups and many in the MBCT cohort were able to stop taking their anti-depressants.

Researchers said their findings suggest MBCT could provide a much-needed alternative for millions of people who cannot or do not wish to take drugs.

In separate research published in 2014, scientists at John Hopkins University reviewed more than 18,000 studies looking at the relationship between mindfulness meditation and depression and anxiety.

The results of the review showed that mindfulness mediation programs were able to moderately reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety.

However, much more research into the potential benefits and risks of mindfulness is needed as much of it lacks consistency and fails to meet rigorous scientific protocols, a group of leading American scientists argued in a 2017 paper.

“There is a common misperception in public and government domains that compelling clinical evidence exists for the broad and strong efficacy of mindfulness as a therapeutic intervention,” they wrote in an article entitled Mind the Hype.

The reality is that mindfulness-based therapies have shown “a mixture of only moderate, low or no efficacy, depending on the disorder being treated,” the scholars said.

One of the biggest problems with research in this area is that there is no universally accepted definition of mindfulness, making it hard to compare results.

“Without specific, well-defined terms to describe not only practices but also their effects, studies of [mindfulness] interventions […] cannot provide valid and comparable measurements to produce reliable evidence,” they concluded.

What’s the consensus?

Studies suggest that mindfulness-based interventions can have moderate benefits for some people with depression and anxiety. However, more rigorous research, as well as a clearer definition of mindfulness, is needed.

-

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber Sands

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber SandsThe Week Recommends Nestled behind the dunes, this luxury hotel is a great place to hunker down and get cosy

-

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in Iraq

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in IraqThe Week Recommends Charming debut from Hasan Hadi is filled with ‘vivid characters’

-

Kia EV4: a ‘terrifically comfy’ electric car

Kia EV4: a ‘terrifically comfy’ electric carThe Week Recommends The family-friendly vehicle has ‘plush seats’ and generous space

-

‘Longevity fixation syndrome’: the allure of eternal youth

‘Longevity fixation syndrome’: the allure of eternal youthIn The Spotlight Obsession with beating biological clock identified as damaging new addiction

-

RFK Jr. sets his sights on linking antidepressants to mass violence

RFK Jr. sets his sights on linking antidepressants to mass violenceThe Explainer The health secretary’s crusade to Make America Healthy Again has vital mental health medications on the agenda

-

The app tackling porn addiction

The app tackling porn addictionUnder the Radar Blending behavioural science with cutting-edge technology, Quittr is part of a growing abstinence movement among men focused on self-improvement

-

Scientists have identified 4 distinct autism subtypes

Scientists have identified 4 distinct autism subtypesUnder the radar They could lead to more accurate diagnosis and care

-

'Wonder drug': the potential health benefits of creatine

'Wonder drug': the potential health benefits of creatineThe Explainer Popular fitness supplement shows promise in easing symptoms of everything from depression to menopause and could even help prevent Alzheimer's

-

Fly like a breeze with these 5 tips to help cope with air travel anxiety

Fly like a breeze with these 5 tips to help cope with air travel anxietyThe Week Recommends You can soothe your nervousness about flying before boarding the plane

-

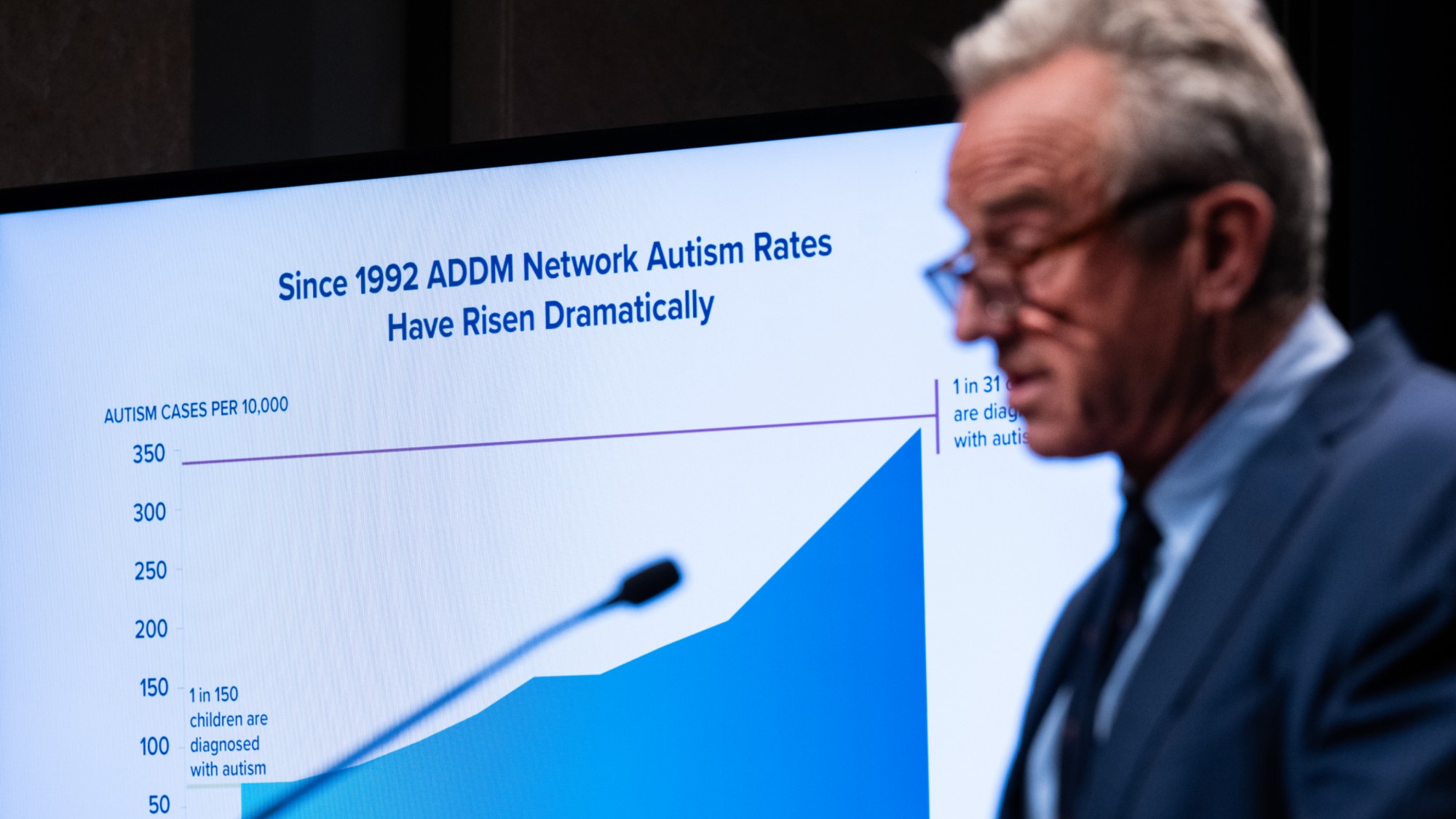

RFK Jr.'s focus on autism draws the ire of researchers

RFK Jr.'s focus on autism draws the ire of researchersIn the Spotlight Many of Kennedy's assertions have been condemned by experts and advocates

-

Mental health: a case of overdiagnosis?

Mental health: a case of overdiagnosis?Talking Point Issues at 'the milder end of the spectrum' may be getting wrongly pathologised