This is the most underrated technique to fight the pandemic

Why everyone should be talking about indoor air quality this winter

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Omicron wave of coronavirus is starting in America. Cases are soaring from Arizona to Maine, even in states with higher vaccination rates (it seems that while two-dose vaccination continues to provide very good protection against hospitalization and death, effectiveness against symptomatic transmission fades after a few months, and the U.S. is behind the curve on booster shots). The new variant will likely constitute the bulk of cases within a few weeks or so.

Meanwhile, if South Africa is any guide, it seems that Omicron has substantial ability to evade immunity induced by a prior infection, and therefore the American South — which was devastated by the Delta wave this summer but is still alarmingly behind on vaccination — is probably in for a bad time. Another dismal pandemic winter is nigh, alas, though hopefully not as bad as the last one.

America needs to broaden its pandemic-fighting tactics — particularly regarding indoor air quality. Better ventilation and filtration inside buildings could do a great deal to slow the spread of coronavirus, as well as reduce illness and death of all kinds in the future.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Since the pandemic started, it's become a cliché that it's very hard to catch COVID-19 outdoors. Where an aerosol virus can float and travel long distances or hang in the air for hours inside, outside it generally dissipates rapidly.

It's not that hard to make an indoor space similar to outdoors in this respect. You just need some combination of ventilation — that is, regularly replacing the indoor air with outdoor air — and filtration. Airlines are an excellent proof of concept. One would think that sitting in a tin can for hours with people packed in like sardines would be a huge infection risk, but airlines have rapid air purification systems that both continually introduce new fresh air and filter it through hospital-grade HEPA filters. Sure enough, despite hundreds of millions of people having flown over the past 20 months, there are only a few dozen confirmed cases of coronavirus transmission on airlines.

Now, it would be very expensive to set up hospital-grade ventilation and filtration systems in every building in the country. HVAC systems cost thousands of dollars, and in a building of any size, a full rework to get good, consistent circulation in every room would take months (though this should be done where possible, especially in older schools that often don't even have climate control at all and badly need an upgrade anyway). However, it's not hard to make substantial improvements. Half-decent ventilation can be as easy as opening two windows to get a cross-breeze going, or placing an intake fan in one and an exhaust fan in the other.

If your home has central air or heating, you can simply buy a HEPA filter (only $170 or so for a decent model), and place it near the furnace intake, or get MERV-13 or better filters for the furnace (about $15-20 apiece), or place filters in individual rooms with poor circulation, or all three. Or in a pinch, you can even make a reasonably effective machine with four high-grade furnace filters, a box fan, some cardboard, and duct tape. Both expert opinion and initial research suggest that such devices do indeed capture most coronavirus particles. The better the ventilation and filtration, the safer the space.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Of course, it's going to be important to continue to wear masks indoors for the foreseeable future. But if we had to pick one, air quality is probably more effective than masking. A simulation study in Germany from last year estimated that in large venues, good ventilation cut down transmission more than masking. And if my hometown of Philadelphia is any guide, even responsible people seldom wear their masks up to a medical standard — they have their nose hanging out, or the fit is bad, or they're wearing cloth masks that are barely better than nothing. In much of the rest of the country, masks aren't worn at all, and many conservatives have violently attacked others over mask mandates. Ventilation is handily centralized and doesn't require compliance from right-wingers with oppositional defiance disorder.

The second big reason to attack unclean air has nothing to do with COVID — it's about the flu. Since the pandemic started, conservatives and sundry anti-vaccine nutcases have compared COVID to influenza as a way of downplaying its danger. If it's "just the flu" then it can't be that bad, the argument goes. In reality, while COVID is much, much worse than the typical flu, as Jeremy Chrysler writes at The Air Letter, there are strong reasons to think that the flu is much worse than popularly supposed.

Flu deaths are not measured remotely as thoroughly as coronavirus cases have been, and it's a safe bet that many or even most cases are missed in official statistics, along with many directly flu-caused deaths. There are also strong seasonal trends to the rates of heart attacks and strokes that track exactly with flu season. Studies suggest that many of these might be triggered by an inflammatory response to a flu infection that is never caught. If so, that means annual influenza-caused deaths might be on the order of 90,000.

The good news about the flu is that it is much, much less contagious than the coronavirus. All the various pandemic control measures nearly eradicated it entirely in the 2020-21 flu season, and improvements to indoor air quality will be even more effective at preventing its transmission than that of COVID. There is every reason to try to make future flu seasons as minor as the last one.

Finally, of course, many homes have substantial indoor pollution problems from gas stoves, cooking, wildfires, or other sources, which filtration can address.

Historian Richard White points out in his book The Republic for Which It Stands that American life expectancy declined for almost the entire 19th century. It started to increase during the Progressive Era in part because of a sustained attack on outdoor pollution: Cities built sewer systems and water treatment plants, cleaned up rivers, lakes, and streams, set up garbage collection and landfills, and so on, which cut down on disease and poisoning. Decades later, further improvements to outdoor air quality from catalytic converters, banning leaded gasoline, smokestack scrubbers, and other measures added more years to American lifespans.

It's time to bring that well-scrubbed spirit indoors, and suck the viruses out of our homes and businesses.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

5 recent breakthroughs in biology

5 recent breakthroughs in biologyIn depth From ancient bacteria, to modern cures, to future research

-

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkiller

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkillerUnder the radar The process could be a solution to plastic pollution

-

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.Under the radar Humans may already have the genetic mechanism necessary

-

Is the world losing scientific innovation?

Is the world losing scientific innovation?Today's big question New research seems to be less exciting

-

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves baby

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves babyspeed read KJ Muldoon was healed from a rare genetic condition

-

Humans heal much slower than other mammals

Humans heal much slower than other mammalsSpeed Read Slower healing may have been an evolutionary trade-off when we shed fur for sweat glands

-

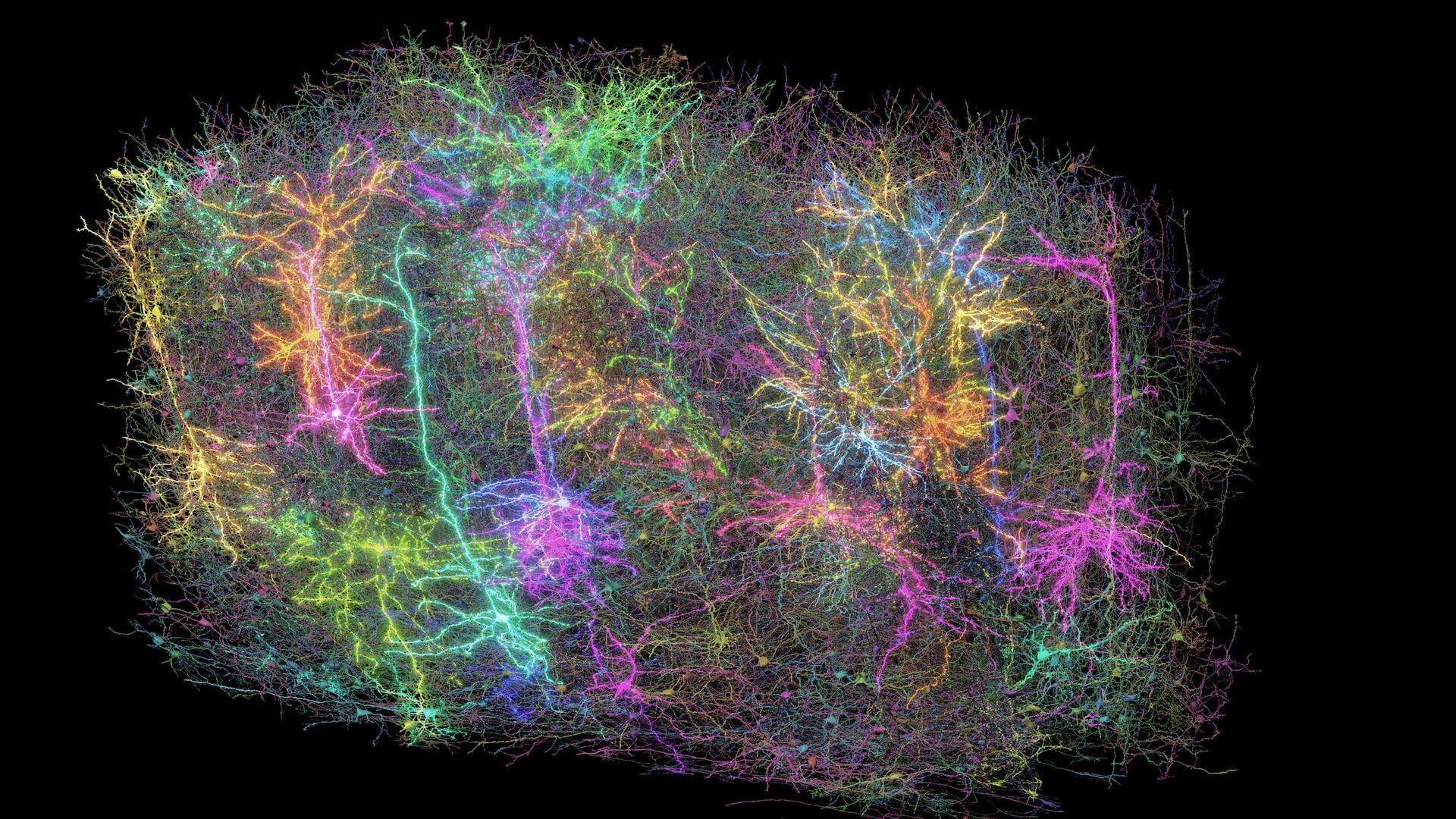

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brain

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brainSpeed Read Researchers have created the 'largest and most detailed wiring diagram of a mammalian brain to date,' said Nature

-

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'Speed Read A 'de-extinction' company has revived the species made popular by HBO's 'Game of Thrones'