Malaria is spreading, but we can stop it

Climate change is hastening the disease but medicine is catching up

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The mosquito-borne illness malaria has been spreading wider and faster as the climate changes. The disease can kill up to 600,000 people every year, per The Guardian. Malaria cases have been largely concentrated in Africa with Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania and Niger accounting for more than half of the malaria deaths between 2021 and 2022, per the latter year’s World Malaria Report.

However, multiple U.S. states have now seen cases not originating from malaria-prone regions. Prior to 2023, "locally acquired mosquito-borne malaria had not occurred in the United States since 2003," according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The good news is that a new vaccine against malaria has hit the market, which could be a turning point in disease transmission.

Why is malaria spreading?

Much of it has to do with shifting climate trends, as warmer temperatures are expanding the viable range for mosquitos. "Efforts to fight malaria are at this crossroads and have been seriously challenged by climate change," Sherwin Charles, the co-founder of organization Goodbye Malaria, told The Washington Post. "We thought we knew how to deal with this epidemic, but the complication of climate change brings different factors to bear that maybe we are not ready for." An analysis by the Post predicts that approximately five billion people will be at risk of contracting malaria by 2040.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The disease is not yet a huge risk in the U.S. as the numbers are still low. But this may not be the case going forward. "Because malaria transmission in the United States has not been a big issue, there is no surveillance of Anopheles [marsh mosquito] populations," explained Photini Sinnis, a professor at the Johns Hopkins University Malaria Research Institute. "Malaria used to come in a certain period — the rainy, hot season … but right now, throughout the year, the mosquitoes multiply," Adamo Palame, a health coordinator who works for Doctors Without Borders, told the Post.

The disease itself is not contagious between person to person and is only spread through the bite of the Anopheles stephensi mosquito. Malaria itself is a parasite found in the red blood cells of an infected person. It can cause flu-like symptoms including fever, chills, shakes, muscle aches, nausea and vomiting, per the CDC. People with weakened immune systems, children and pregnant women can have a higher risk of dying from the disease.

How effective will the vaccine be?

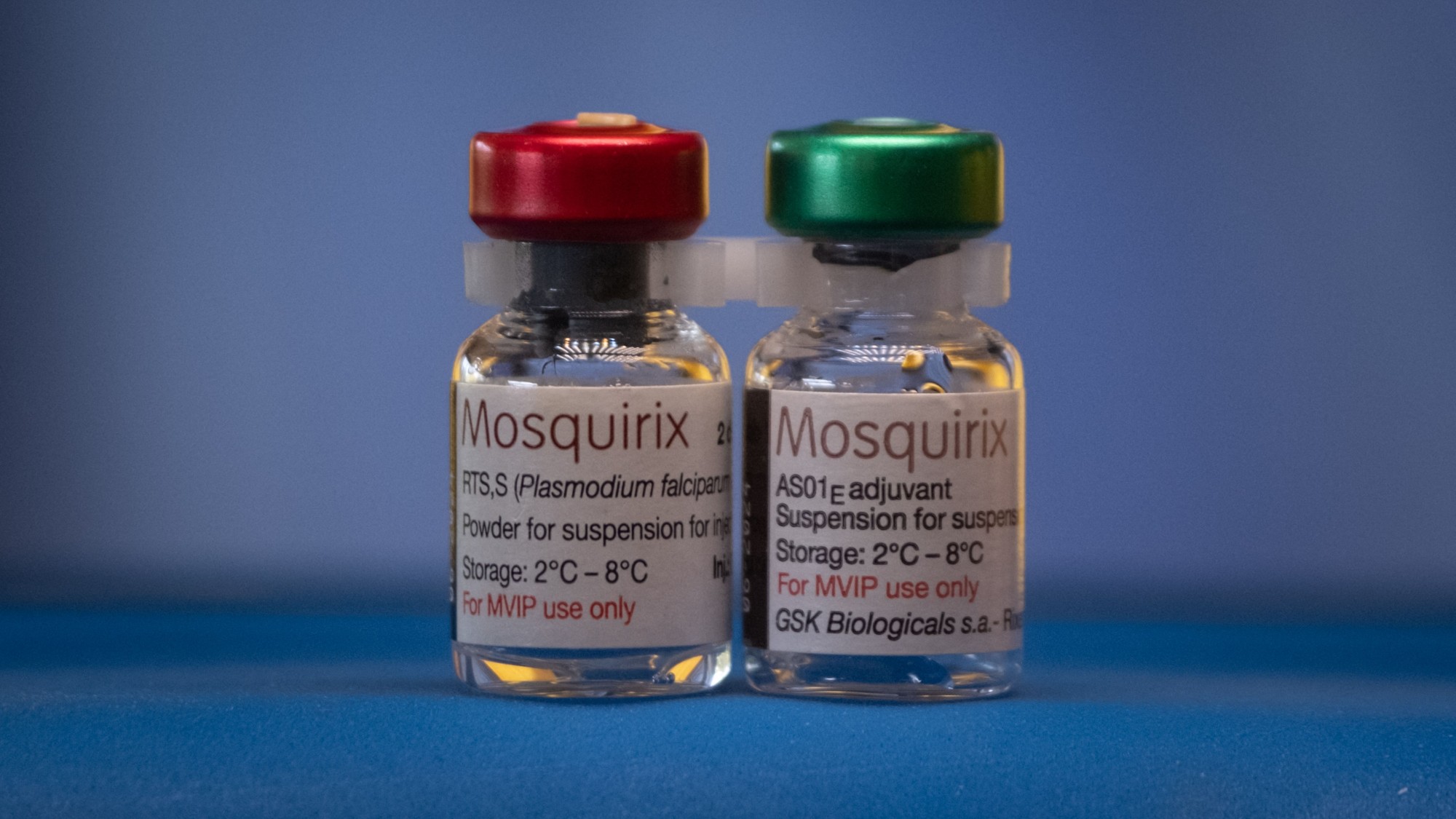

Starting next year, there will be two vaccines on the market to combat malaria. The first one, the RTS,S/AS01 vaccine, received a World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation in 2021. The new one, the R21/Matrix-M vaccine, was recommended in October 2023 and will be rolled out in mid-2024. While the makeups of the vaccines are similar, the R21 has plans to be produced in much larger numbers. "I used to dream of the day we would have a safe and effective vaccine against malaria. Now we have two," WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a statement. "Demand for the RTS,S vaccine far exceeds supply, so this second vaccine is a vital additional tool to protect more children faster." R21 will be administered in four doses, starting when the child is five months old and ending when they are two.

Many are hopeful about the vaccine’s possibilities. "This second vaccine holds real potential to close the huge demand-and-supply gap," Matshidiso Moeti, the WHO’s regional director for Africa, told The Guardian. While the first vaccine only had 18 million doses while the second is on track to have 100 million. "The estimates are that by adding the vaccine to the current tools that are in place … tens of thousands of children's lives will be saved every year," Mary Hamel, a senior technical officer with WHO, told NPR.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

On the other hand, the four-shot dosage of the vaccine could pose problems for some families, who may have "travel to clinics, taking time out from the fields or hard work at home, perhaps bringing other children too," The Guardian wrote. Nick White of Mahidol University in Thailand and Oxford added that "in Africa, malaria maps to its wars," and that "large swathes of Africa will not be able to receive" the vaccine.

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

‘Zero trimester’ influencers believe a healthy pregnancy is a choice

‘Zero trimester’ influencers believe a healthy pregnancy is a choiceThe Explainer Is prepping during the preconception period the answer for hopeful couples?

-

Scientists are worried about amoebas

Scientists are worried about amoebasUnder the radar Small and very mighty

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue Tui after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

Metal-based compounds may be the future of antibiotics

Metal-based compounds may be the future of antibioticsUnder the radar Robots can help develop them

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

Is the US about to lose its measles elimination status?

Is the US about to lose its measles elimination status?Today's Big Question Cases are skyrocketing

-

A real head scratcher: how scabies returned to the UK

A real head scratcher: how scabies returned to the UKThe Explainer The ‘Victorian-era’ condition is on the rise in the UK, and experts aren’t sure why

-

Mixed nuts: RFK Jr.’s new nutrition guidelines receive uneven reviews

Mixed nuts: RFK Jr.’s new nutrition guidelines receive uneven reviewsTalking Points The guidelines emphasize red meat and full-fat dairy