The ethics of having children in the age of climate change

International survey finds one in four young people ‘hesitant’ about starting families amid global warming fears

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In an age of increasingly frequent “freak” weather events and warnings about global warming, the future of our planet is looking increasingly uncertain.

As experts predict that some of the effects of climate change will be “irreversible”, a growing number of young people are becoming reluctant to bring children into the world, a newly published study in The Lancet revealed.

In a global poll of 10,000 people aged 16 to 25, three-quarters agreed that “the future is frightening”, while just 31% felt that their governments were “doing enough to avoid catastrophe”.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And 39% are “hesitant to have children”, according to the findings of the survey, which covered Australia, Brazil, Finland, France, India, Nigeria, the Philippines, Portugal, the UK and the US.

“I meet a lot of young girls, who ask whether it’s still OK to have children,” German climate activist Luisa Neubauer told The Guardian. “It’s a simple question, yet it tells so much about the climate reality we are living in.”

The moral conundrum has become a hot topic in recent years. In 2019, New York congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez made headlines after questioning the environmental ethics of childbearing.

“Our planet is going to hit disaster if we don’t turn this ship around... there’s scientific consensus that the lives of children are going to be very difficult,” she said in an Instagram livestream.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Ocasio-Cortez’s comments were met with what Business Insider described as “blowback from conservative pundits”, who argued that she was effectively “advocating for a ban on children”.

As the debate rages on, activists point to the carbon footprint that each new human life creates. A 2017 study published in Environmental Research journal by Canadian climate scientists found that a child born into the global north left a 58.6 metric tonne carbon footprint annually, on average.

This carbon footprint is lower in undeveloped countries, however, with that of a child in Malawi estimated to be no more than 0.1 metric tonnes annually, according to the BBC.

Along with ditching cars, avoiding air travel and eating a plant-based diet, the Canadian study recommended that people could reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by reducing the number of children they have by one.

High-profile figures who appear to back this strategy of having smaller families include Prince Harry and Meghan Markle. The Duke of Sussex told Vogue in 2019 that he would have a “maximum” of two children, citing environmental concerns.

Such concerns typically range from “what harm will my child do to the world?” to “what sort of harm will a hotter and more violent, less stable world do to my child?” said Meghan Kallman, the co-founder of Conceivable Future, a grassroots network of Americans who feel conflicted about starting a family against the backdrop of climate chaos.

“The future is so incredibly uncertain... it’s really terrifying to contemplate the prospect of kids you have or kids you might have,” she told the BBC.

Not everyone is convinced that having fewer children is the best way to protect our planet’s future. “If we consider the child solely as an individual unit of consumption, an aspect of their parent's carbon footprint just as eating a steak or taking a flight might be, then yes, their existence could well be a bad thing,” wrote Tom Whyman in digital tech and trends magazine The Outline.

“But this is a really strange way to consider a human life,” he continued. “Every new human being exists, in part, to carry on the human species - but they also act transformatively within the world.”

Critics of the fewer children approach often point to both the social and economic implications. Europe’s low birth rate and fast-ageing population has been described as a “demographic time-bomb” by the FT.

“There is serious concern about the impact of an ageing population on public finances and economic growth,” said the paper.

Ultimately, of course, whether to have children in the age of climate change remains a personal choice.

Even climate scientist Kimberley Nicholas, who co-authored the 2017 Canadian study that recommended having fewer children, has argued that people who really want to become parents should do so.

Speaking to Vox’s Sigal Samuel in April about why “it’s still OK to have kids”, Nicholas argued that to “leave fossil fuels in the ground and switch to regenerative and sustainable agriculture” would make more of an impact in tackling climate change than controlling the population.

“It is true that more people will consume more resources and cause more greenhouse gas emissions,” she said. “But that’s not really the relevant timeframe for actually stabilising the climate, given that we have this decade to cut emissions in half.”

Samuel has put forward another powerful argument in the childbearing debate. “Children aren’t just emitters of carbon,” she wrote in an article last year. “They’re also extraordinarily efficient emitters of joy and meaning and hope.

“Those sentiments are what will hopefully motivate us to keep pushing for the changes our world desperately needs.”

Kate Samuelson is The Week's former newsletter editor. She was also a regular guest on award-winning podcast The Week Unwrapped. Kate's career as a journalist began on the MailOnline graduate training scheme, which involved stints as a reporter at the South West News Service's office in Cambridge and the Liverpool Echo. She moved from MailOnline to Time magazine's satellite office in London, where she covered current affairs and culture for both the print mag and website. Before joining The Week, Kate worked at ActionAid UK, where she led the planning and delivery of all content gathering trips, from Bangladesh to Brazil. She is passionate about women's rights and using her skills as a journalist to highlight underrepresented communities. Alongside her staff roles, Kate has written for various magazines and newspapers including Stylist, Metro.co.uk, The Guardian and the i news site. She is also the founder and editor of Cheapskate London, an award-winning weekly newsletter that curates the best free events with the aim of making the capital more accessible.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacier

The plan to wall off the ‘Doomsday’ glacierUnder the Radar Massive barrier could ‘slow the rate of ice loss’ from Thwaites Glacier, whose total collapse would have devastating consequences

-

Can the UK take any more rain?

Can the UK take any more rain?Today’s Big Question An Atlantic jet stream is ‘stuck’ over British skies, leading to ‘biblical’ downpours and more than 40 consecutive days of rain in some areas

-

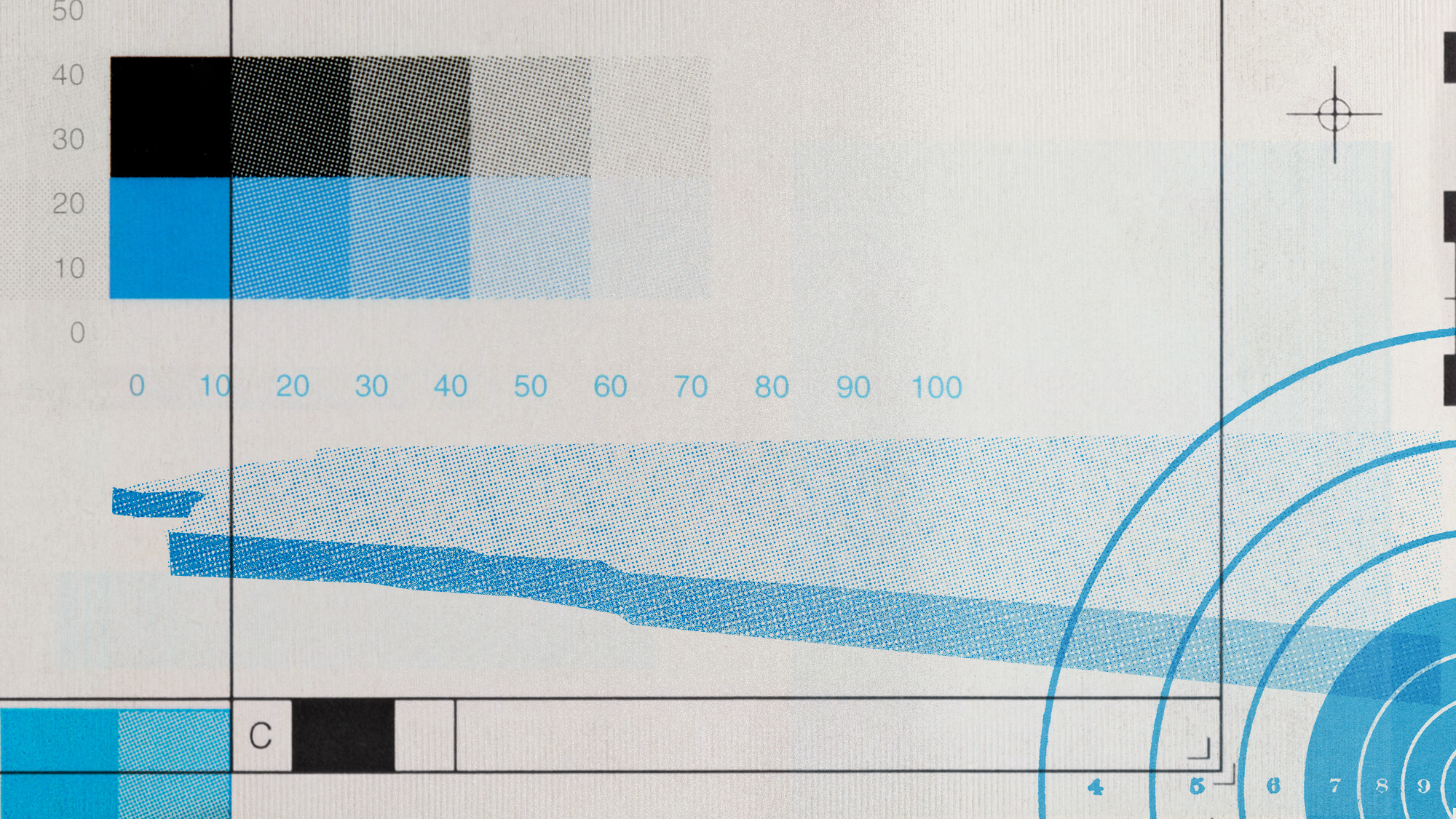

As temperatures rise, US incomes fall

As temperatures rise, US incomes fallUnder the radar Elevated temperatures are capable of affecting the entire economy

-

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.Under the radar It is quickly melting away

-

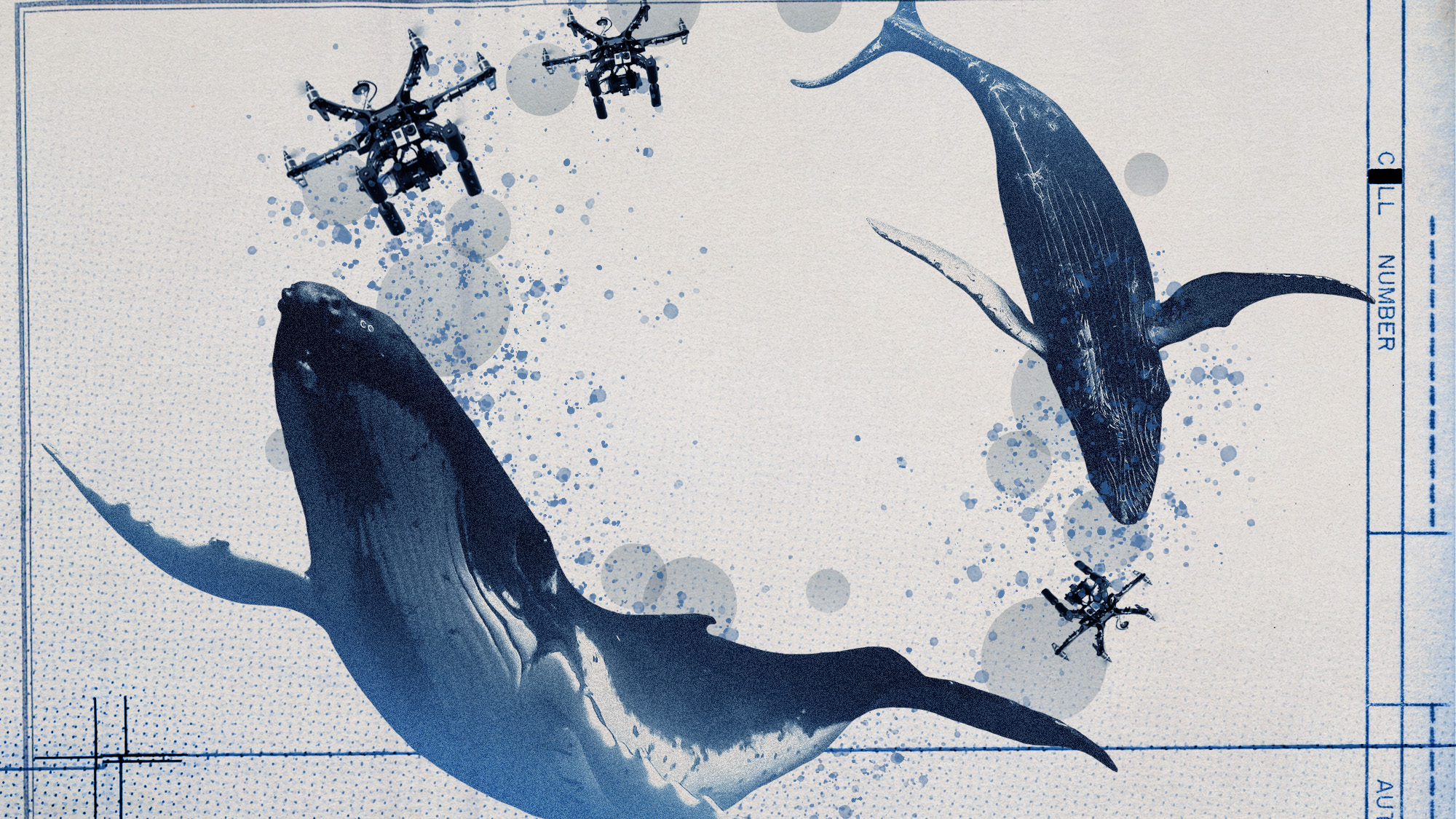

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whales

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whalesUnder the radar Monitoring the sea in the air

-

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming Arctic

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming ArcticUnder the radar The species is adapting to warmer temperatures