Extreme heat: how much worse will it get?

Heatwaves fuelled by climate crisis are becoming more frequent and putting millions of lives at risk

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Large swathes of the planet are in the grip of deadly heatwaves fuelled by the climate crisis, with tens of millions sweltering in record-breaking temperatures in India, the US and the Middle East.

An atmospheric heat dome is sitting over more than half of the US, and one in five Americans were under heat alerts as of Wednesday. In India, temperatures have broken 50C in some areas, and at least 60 people died between March and May due to heat-related illnesses, said the BBC. On Monday, the Islamic Hajj pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia came to an end in temperatures of 51.8C, with more than a dozen heat-related deaths confirmed and many more reported.

What did the commentators say?

Extreme heat already causes more deaths each year than any other weather event – but the world can expect more, according to the EU's Copernicus Climate Change Service. Last year was the hottest year on record, and so far 2024 has continued this trend, with May being the 13th month in a row to break temperature records. And Europe's temperatures are rising twice as fast as the global average, according to a joint report by the UN and European Union published in April.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Greece has been among the worst-affected countries. TV doctor Michael Mosley, who was found dead this month after hiking in scorching temperatures, was just "one of a series of tourist deaths and disappearances", said CNN. "There is a common pattern," Petros Vassilakis, police spokesman for the southern Aegean, told Reuters. "They all went for a hike amid high temperatures."

High temperatures dramatically increase the risk of heart attacks and heatstroke, particularly among older people and those with chronic diseases. Even young, healthy people are affected, said The New York Times. Heat "takes a toll on our brains, impairing cognition and making us irritable, impulsive and aggressive", it said.

Scientists warn that extreme heat could one day make it "impossible" to hold the Olympics in the summer. Ahead of the Paris Games next month, former Olympians and heat physiologists from the University of Portsmouth said in a report this week that rising temperatures could lead to athletes collapsing, or even dying.

Last year, about 2,300 deaths in the US were attributed to extreme temperatures, according to The Associated Press. Some of the deadliest heat was in the southwestern regions: "a warning sign that there's an upper limit to heat tolerance even in a region otherwise accustomed and adapted to hot weather," said Vox.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Since March, at least 125 people have died in Mexico, where the temperature hit a June record of almost 52C. The death toll across Central America, one of the world's most vulnerable regions to the climate crisis due to geography, poor infrastructure and high inequality, is unknown, said The Guardian.

But "most of the inhabited world" need not worry, said Scott Denning, professor of atmospheric science at Colorado State University, on The Conversation. It's never going to get too hot to live in "relatively dry climates", because our bodies can cool off by evaporating water and heat from our skin.

The most dangerous places are those that get hot and humid – for example, the Middle East, Pakistan and India, where hundreds of millions live, mostly with no access to air conditioning. In humid air, "sweat doesn't evaporate as quickly". Prolonged exposure to high heat and humidity "can be truly deadly".

What next?

Even if countries deliver on their emissions reduction pledges under the 2015 Paris Agreement, the UN environment programme estimates at least a 2.5C rise in global temperatures by the end of the century.

"The bad news is that as long as we keep burning carbon, it will continue to get hotter and hotter," said Denning on The Conversation. "The good news is that we can substitute clean energy, like solar and wind power, instead of burning carbon." In this way, "we will avoid making our world unlivable".

Increasing access to cooling and air conditioning "needs to be part of the solution", said Vox. People who are experiencing homelessness or can't afford cooling are at much greater risk during heatwaves. "Many more hot days are ahead, but more people don't have to die."

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

The price of sporting glory

The price of sporting gloryFeature The Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics kicked off this week. Will Italy regret playing host?

-

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?Feature Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard is Trump's de facto ‘voter fraud’ czar

-

Fifteen years after Fukushima, is Japan right to restart its reactors?

Fifteen years after Fukushima, is Japan right to restart its reactors?Today’s Big Question Balancing safety fears against energy needs

-

Can the world adapt to climate change?

Can the world adapt to climate change?Today's Big Question As the world gets hotter, COP30 leaders consider resilience efforts

-

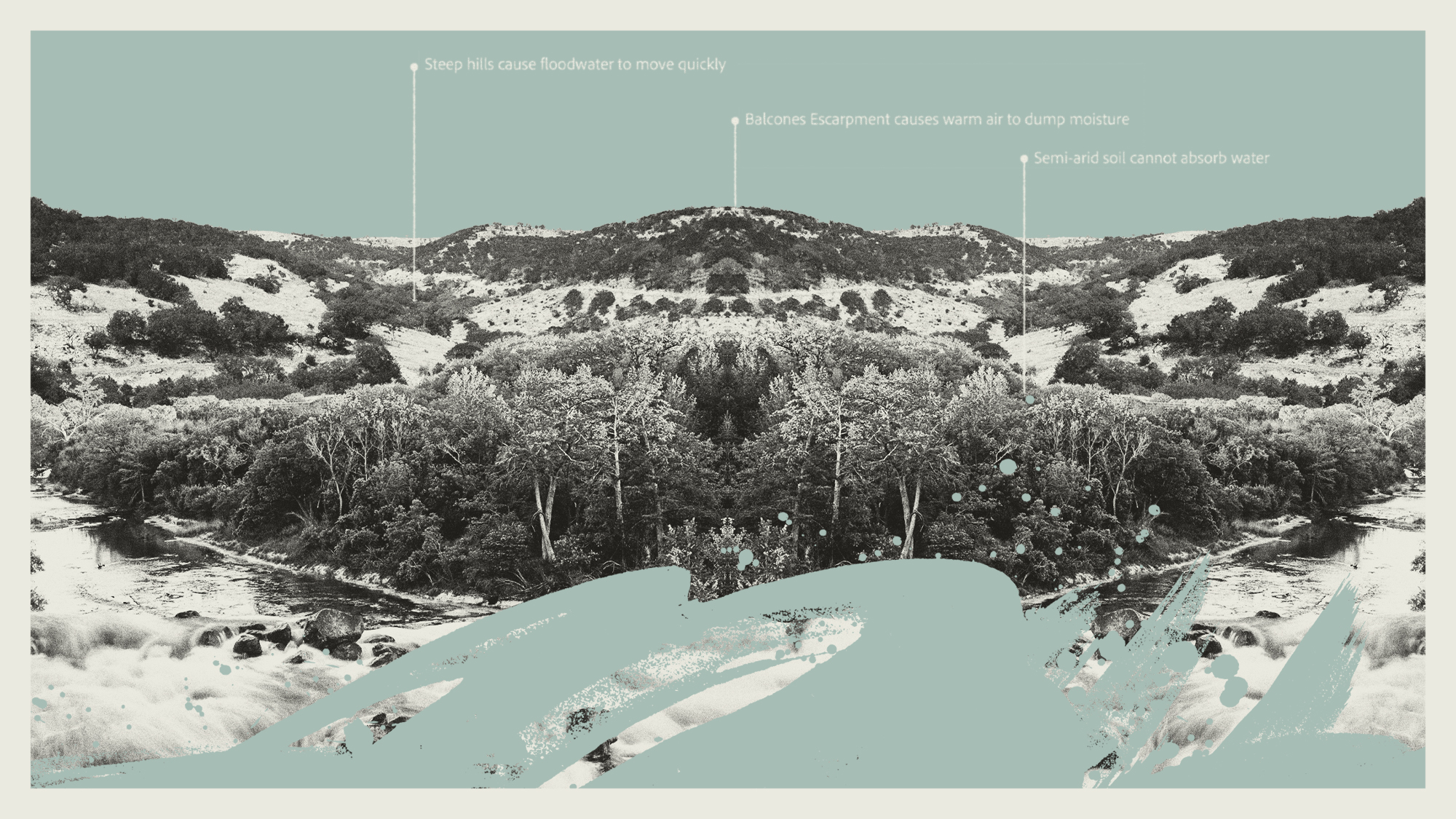

Why are flash floods in Texas so deadly?

Why are flash floods in Texas so deadly?Today's Big Question Over 100 people, including 27 girls at a summer camp, died in recent flooding

-

What are Trump's plans for the climate?

What are Trump's plans for the climate?Today's big question Trump's America may be a lot less green

-

Starmer vs the farmers: who will win?

Starmer vs the farmers: who will win?Today's Big Question As farmers and rural groups descend on Westminster to protest at tax changes, parallels have been drawn with the miners' strike 40 years ago

-

Is Cop29 a 'waste of time'?

Is Cop29 a 'waste of time'?Today's Big Question World leaders stay away as spectre of Donald Trump haunts flagship UN climate summit

-

Why is Mexico City running out of water?

Why is Mexico City running out of water?Today's Big Question Climate change and bad planning bring on 'Day Zero'

-

Is America running out of electrical power?

Is America running out of electrical power?Today's Big Question The nation's power grid appears to be reaching critical levels due to emerging technologies