Does the Anglosphere exist?

Do the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States share more than a language?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The UK, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the US all share the same language – but are our assumed commonalities real or imagined?

As a loose definition, the Anglosphere “is the name given to all those countries in the world where the majority of people speak English as their first language, almost all of which have similar outlooks and shared values”, said The Wall Street Journal in 2020.

The term is usually taken to encompass Australia, Canada, New Zealand the UK and the US, but can also include the Republic of Ireland, Malta and Commonwealth Caribbean countries.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Anglosphere is generally used to describe an assumed bond between English-speaking countries by way of a shared language and its associated forms of literature, culture, sport and family ties. It also refers to a common history of military collaboration in the First and Second World Wars, and an assumption of shared values over the idea of liberal democracy and free-market trade.

The five “core” countries of the Anglosphere have maintained close diplomatic, military and cultural links, and all but the US have had Elizabeth II as their head of state.

CANZUK

Since the emergence of Euroscepticism in the early 1990s some – mainly right-wing – groups and thinkers have argued for a “federation” between four of the five core nations of the so-called Anglosphere – Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom – which is often referred to as CANZUK.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As historian and Winston Churchill biographer Andrew Roberts argued in The Wall Street Journal, this federation would allow “free trade, free movement of people, a mutual defense organization and combined military capabilities” in the hopes of creating a “new global superpower and ally of the U.S., the great anchor of the Anglosphere”.

Roberts went on: “The Canzuk Union would immediately enter the global stage as a superpower, able to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the U.S. in the great defining struggle of the 21st century against an increasingly revanchist China.”

Anglosphere vs. EU

In the UK, the emergence of right-wing Euroscepticsm in the 1990s saw a “renaissance of Anglospherism as an alternative to membership of the European Union”, argued Andrew Mycock, a reader in politics at the University of Huddersfield, and Ben Wellings, a senior lecturer in politics and international relations at Monash University, in The British Academy Review in 2017.

After the Conservative Party returned to power in 2010, leading figures such as the then foreign secretary William Hague and the mayor of London, Boris Johnson, “sought to exemplify the potential of the Anglosphere as a counterweight to Europe by seeking to intensify links with conservative-led governments amongst Britain’s ‘traditional allies’ in Australia, Canada and New Zealand,” while Leave campaigners “also made explicit reference to the potential of the Anglosphere”, with the idea providing a “point of commonality amongst those campaigning for Brexit”.

Five Eyes

Perhaps the most concrete part of the notion of an Anglosphere is the existing “Five Eyes” intelligence-sharing alliance between the US, UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

As the BBC explained, Five Eyes “evolved during the Cold War as a mechanism for monitoring the Soviet Union and sharing classified intelligence” and is “often described as the world’s most successful intelligence alliance”.

In May 2020, the group decided to expand its role away from “just security and intelligence to a more public stance on respect for human rights and democracy”, as it was assumed the five nations broadly shared the same world view.

But some cracks are beginning to appear in the alliance over relations with China. In May, New Zealand refused to join condemnation of Bejing’s de-facto takeover of the South China Sea. New Zealand’s foreign minister Nanaia Mahuta said the country “felt uncomfortable” with expanding the alliance's role by putting pressure on China over its activities in the disputed region.

New Zealand’s stance has prompted some to “question whether the alliance is in trouble”, or if the nation was merely drawing a distinction between politics and intelligence. “In retrospect it was an overstretch of what Five Eyes was meant for: sharing secrets,” said the BBC.

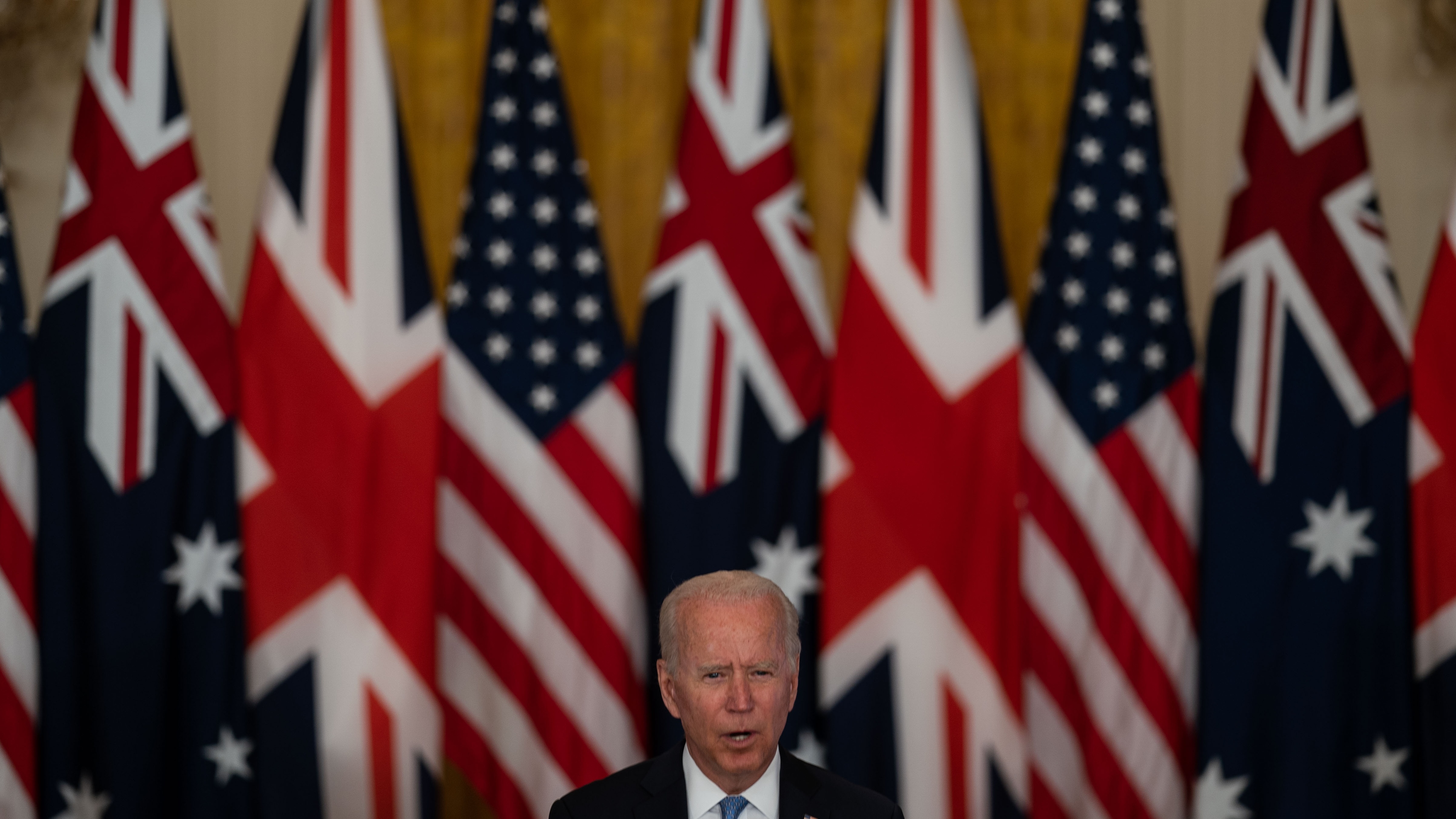

In September 2021, ties between Australia, the UK and the US were further strengthened by the agreement of a historic security pact between the three nations – Aukus – designed to counter emerging threats in the Indo-Pacific region.

As part of the agreement, Australia will be able to build nuclear-powered submarines for the first time, using technology provided by the US.

Does the Anglosphere really exist?

“Whenever anyone has tried to actually apply the idea of an Anglosphere, in its various guises, it has always collided with reality,” argued Michael Kenny, professor of public policy at the University of Cambridge, and Nick Pearce, director of the Institute for Policy Research at the University of Bath, in The New York Times in 2018.

They said that “economic interest or politics or national security has never been enough to persuade the peoples of these different countries to enter into an Anglosphere alliance” and that the other four “core” members of the Anglosphere “show no inclination to join Britain in new political and economic alliances” and would “rather continue to work within the existing institutions” such as the EU or the World Trade Organization.

British journalist Nick Cohen has frequently criticised the idea of an Anglosphere as an alternative to the UK’s membership of the European Union, calling it “the right’s PC replacement for what we used to call in blunter times ‘the white Commonwealth’”.

In The Spectator, he wrote: “The dream that has the Eurosceptics talking in their sleep is that we can forge new bonds with the old empire, or at least the white dominated countries within it, and regain a part of what we once were.”

The pandemic has also brought to light major differences between the Anglosphere nations, argued Janan Ganesh in the Financial Times this week.

“If there is such a thing as an ‘Anglosphere’, bound by a deep-seated culture of individualism, why did the member nations diverge so much over the pandemic?” he asked, noting the “relative laxity” of the US’ approach, to “perhaps the severest lockdowns in the western world” in Australasia.

“To the extent that Covid has served as an audit of national cultures, the findings refute the idea of a Washington-to-Wellington communion of values,” wrote the columnist.

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’Feature A grim reaper for software services?

-

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC head

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC headSpeed Read Jay Bhattacharya, a critic of the CDC’s Covid-19 response, will now lead the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

-

Greenland’s capital becomes ground zero for the country’s diplomatic straits

Greenland’s capital becomes ground zero for the country’s diplomatic straitsIN THE SPOTLIGHT A flurry of new consular activity in Nuuk shows how important Greenland has become to Europeans’ anxiety about American imperialism

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire