Will Vladimir Putin be put on trial for Ukraine’s stolen children crisis?

Russian president has been charged with war crimes for abducting thousands of Ukrainian children

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

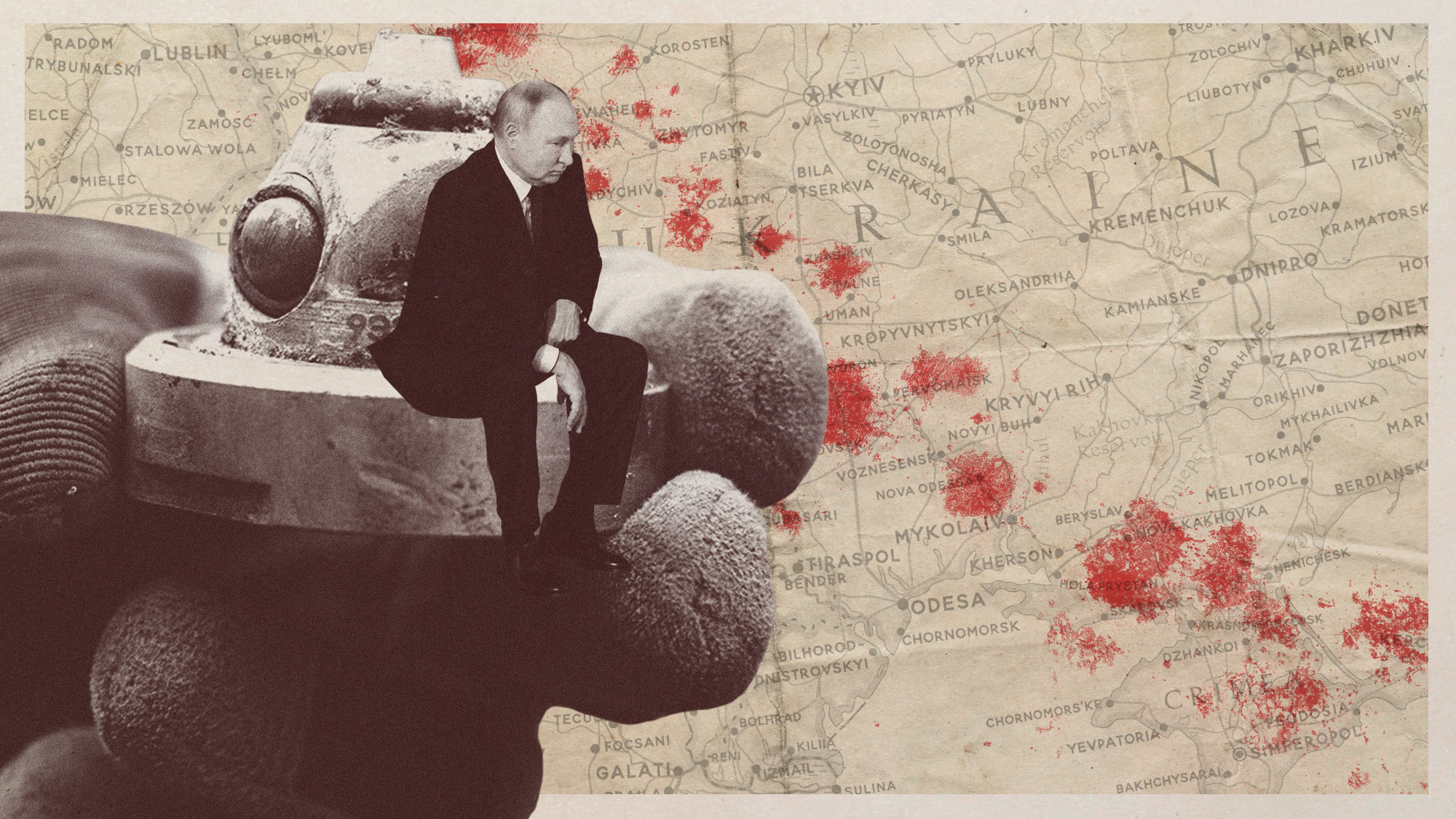

As the war in Ukraine rages on, the International Criminal Court (ICC) last month issued an arrest warrant for Vladimir Putin.

The Russian president and his commissioner for children’s rights, Maria Alekseyevna Lvova-Belova, are accused of illegally deporting hundreds of children from Ukraine during the year-long invasion.

Russia does not recognise the ICC nor extradite its citizens, so “it is highly unlikely that Putin or Lvova-Belova will be surrendered to the court’s jurisdiction any time soon”, said The Guardian. But the issuing of the warrant still represents “a highly significant moment”, the paper added.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What are the charges?

The International Criminal Court (ICC) last month issued an arrest warrant for Vladimir Putin and his commissioner for children’s rights, Maria Lvova-Belova. They were charged with unlawfully seizing and moving children out of Ukraine – a crime against humanity as stipulated in UN human rights conventions and the ICC’s founding treaty, the Rome Statute.

Of the thousands of crimes linked to the Russian president, this is one of the easiest to substantiate. Yale’s Humanitarian Research Lab issued a report in February stating that at least 6,000 Ukrainian children, ranging from infants to 17-year-olds, are known to have been deported from occupied eastern and southern Ukraine to Russia or Crimea without their parents. The true number is likely much higher. Ukraine’s government says it is at least 16,000, and the total number could be as high as 400,000.

How do the abductions take place?

There have been cases recorded dating back as far as 2014, when Russia’s proxy war against Ukraine began. But when the full-scale invasion started last February, the process started happening on an unprecedented scale. Children have been separated from their parents through phony “evacuation orders” and in “filtration camps”, where Russian forces and their proxies search and interrogate Ukrainians leaving conflict zones. Some Ukrainian parents in occupied territories, desperate to get their children out of the warzone, have agreed to send them away for short stays at what were depicted as summer camps, only to have their return indefinitely postponed.

Russian troops have also scooped up children from schools, hospitals and orphanages. Orphanages in pre-war Ukraine held more than 105,000 children – more than any other European country except Russia – but most of them are so-called “social orphans”, meaning they are in care because of poverty or abuse: 90% had living relatives. Russian-backed local government officials have taken over orphanages and arranged for the rapid transfer of children into Russia.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What happens to them?

Some are swiftly put up for adoption, with Russia offering its citizens between $300 and $2,000 in state aid per child per year. The government has staged photo opportunities in which dazed children are welcomed with teddy bears, gift baskets and hugs from strangers. Under a decree signed by Putin last May, they’re then fast-tracked for Russian citizenship. Initially, though, most of the children are placed in a system of re-education camps: the Yale report identified 43 of these, many of them in Russian-occupied Crimea, some clustered around Russia’s biggest cities, and some as far away as its Pacific coast – closer to Alaska than Ukraine.

What is known about the camps?

Their primary purpose is apparently to erase the children’s Ukrainian identity and turn them into patriotic Russians. Inessa Vertash, of Beryslav, in previously occupied Kherson Oblast, reluctantly let her 15-year-old son, Vitaliy, attend a Russian camp at the urging of his school’s headmistress.

After two relatively pleasant weeks, he was moved to another camp that, he said in a rare phone call home, was “like a prison”. Attendees were beaten for refusing to sing the Russian national anthem, sexually abused and psychologically manipulated. “They told the children: ‘Your parents have left Ukraine and are never coming for you,’” Vertash said.

What is Russia’s goal?

Russian propaganda portrays the abductions as humanitarian “evacuations” to get children out of harm’s way. Ukraine’s commissioner for children’s rights, Daria Herasymchuk, describes the programme as “an act of genocide”. “They change their citizenship, give them up for adoption under guardianship, commit sexual violence and other crimes,” she says. Putin wrote an infamous essay in July 2021 arguing that Ukrainian nationhood was a 20th century fabrication, and that Ukrainians and Russians are “one people” – all of whom are Russian, whether they admit it or not. The abductions appear to be an attempt to convince Ukrainian children that this is the case, and to replenish a dwindling Russian population, depleted by a low birth rate, ageing, extensive emigration and the carnage of the war.

Will either Putin or Lvova-Belova be prosecuted?

It’s very unlikely. The deportations would appear to meet the UN’s definition of genocide, which in addition to mass killings includes “forcibly transferring children of the group to another group”, and “deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part”. But Russia (like the US, China and Ukraine) is not a member of the ICC, and the court does not conduct trials in absentia. The Kremlin labelled the charges “outrageous and unacceptable”.

Can the children be rescued?

About 350 children have been returned so far, and the Ukrainian government has asked foreign governments and international organisations for help in retrieving more. But Putin has said that he plans to expand, not abandon, the “Happy Childhood” project in the coming months. Russia makes it difficult, if not impossible, for parents to recover their children. In many cases, it has barred anyone but a child’s legal parent from picking up a child in Russia. Since Ukraine currently bars adult men under 60 from leaving the country, that often means only the mother can make the dangerous, prohibitively expensive journey into Russia via a third country to pick up her children. Olga Lopatkina managed to recover six of her children from occupied Donetsk after months of negotiations. The children had been told to forget her. “Doesn’t Russia have its own kids?” she said. “I have no idea why they need ours. I guess it’s just to hurt us.”

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’Feature New insights into the Murdoch family’s turmoil and a renowned journalist’s time in pre-World War II Paris

-

New START: the final US-Russia nuclear treaty about to expire

New START: the final US-Russia nuclear treaty about to expireThe Explainer The last agreement between Washington and Moscow expires within weeks

-

What would a UK deployment to Ukraine look like?

What would a UK deployment to Ukraine look like?Today's Big Question Security agreement commits British and French forces in event of ceasefire

-

Trump peace deal: an offer Zelenskyy can’t refuse?

Trump peace deal: an offer Zelenskyy can’t refuse?Today’s Big Question ‘Unpalatable’ US plan may strengthen embattled Ukrainian president at home

-

Vladimir Putin’s ‘nuclear tsunami’ missile

Vladimir Putin’s ‘nuclear tsunami’ missileThe Explainer Russian president has boasted that there is no way to intercept the new weapon

-

How should Nato respond to Putin’s incursions?

How should Nato respond to Putin’s incursions?Today’s big question Russia has breached Nato airspace regularly this month, and nations are primed to respond

-

Russia’s war games and the threat to Nato

Russia’s war games and the threat to NatoIn depth Incursion into Poland and Zapad 2025 exercises seen as a test for Europe

-

What will bring Vladimir Putin to the negotiating table?

What will bring Vladimir Putin to the negotiating table?Today’s Big Question With diplomatic efforts stalling, the US and EU turn again to sanctions as Russian drone strikes on Poland risk dramatically escalating conflict

-

Ottawa Treaty: why are Russia's neighbours leaving anti-landmine agreement?

Ottawa Treaty: why are Russia's neighbours leaving anti-landmine agreement?Today's Big Question Ukraine to follow Poland, Finland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia as Nato looks to build a new ‘Iron Curtain' of millions of landmines