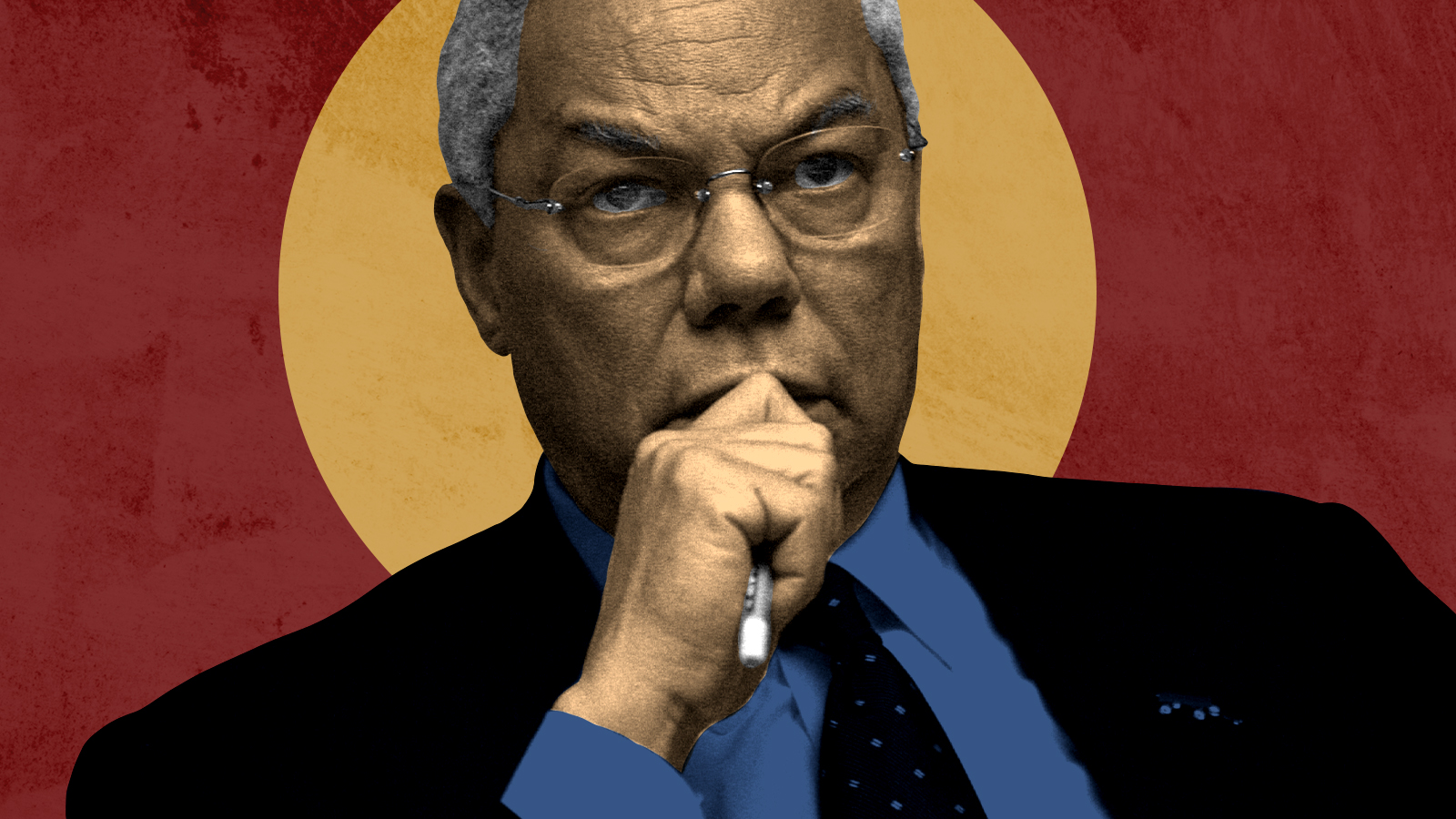

Iraq was Colin Powell at his worst — and most human

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Colin Powell, who died on Monday of complications of COVID-19 at the age of 84, lived an exemplary American life. The child of immigrants from Jamaica, he grew up in the South Bronx, attended public schools, began a military career in ROTC, and rose through the ranks to become a four-star general, chair of the Joint Chiefs, and, after his retirement, secretary of state.

Yet he will likely be remembered, most of all, for lending his name and reputation to the efforts of the George W. Bush administration to build domestic and international support for the American-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. That was the biggest mistake of Powell's career. Reflecting on how he managed to make it teaches an important lesson about the character of political life at its peak.

Powell inclined toward realism in foreign policy. That made him an ideal secretary of state for Bush, who ran for president promising to do less nation building around the world. That support for geopolitical restraint went out the window with the September 11 attacks. First, we invaded Afghanistan. Then the administration began preparing to topple Iraq's Saddam Hussein. Powell's testimony before the United Nations on Feb. 5, 2003 was crucial to justifying American preparations for war in Iraq, because it was supposedly based on rock-solid intelligence about Hussein's ongoing program to develop weapons of mass destruction (WMD). Years later, it was revealed that this intelligence was largely based on unverified claims of an unreliable Iraqi defector living in Germany.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Powell had his doubts, but he kept them to himself. His performance before the U.N. was exemplary and helped to solidify public opinion in favor of military action. This was somewhat surprising, given that press reports prior to Powell's testimony indicated he was more skeptical than most senior members of the administration about the wisdom of taking action in Iraq. Clearly he'd made a decision to play ball.

It was the wrong call — and Powell's reputation suffered for it after no stockpiles of WMD were found, and even more so after the invasion and occupation of the country gave birth to a bloody insurgency and civil war that dragged on for years.

In retrospect, it seems obvious Powell should have made a different decision, opting to resign as secretary of state rather than peddle dubious intelligence as fact before all the world. But in the moment, that was an incredibly high-risk proposition. What if doing so undermined support for the invasion, Hussein turned out to have WMD, and he passed them along to terrorists? Or what if the invasion went forward and huge stockpiles of WMD were found, vindicating the questionable intelligence and making Powell's stand appear irresponsibly timorous?

That's the way it is in public life at the highest levels. Decisions with enormously high stakes need to be made under conditions of maximal uncertainty. When the moment came for Powell's most momentous decision, he flubbed it. It's fitting that he will be remembered for that. But it's also fitting that we recognize the immense burden of such decisions — and how few of us, if placed in the identical situation, would have what it takes to do better.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax

-

Did Alex Pretti’s killing open a GOP rift on guns?

Did Alex Pretti’s killing open a GOP rift on guns?Talking Points Second Amendment groups push back on the White House narrative

-

Washington grapples with ICE’s growing footprint — and future

Washington grapples with ICE’s growing footprint — and futureTALKING POINTS The deadly provocations of federal officers in Minnesota have put ICE back in the national spotlight

-

Trump’s Greenland ambitions push NATO to the edge

Trump’s Greenland ambitions push NATO to the edgeTalking Points The military alliance is facing its worst-ever crisis

-

Why is Trump threatening defense firms?

Why is Trump threatening defense firms?Talking Points CEO pay and stock buybacks will be restricted

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Trump considers giving Ukraine a security guarantee

Trump considers giving Ukraine a security guaranteeTalking Points Zelenskyy says it is a requirement for peace. Will Putin go along?

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story