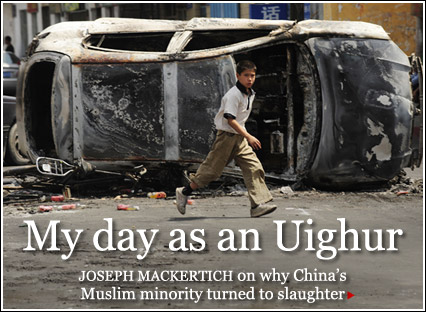

My day as an Uighur Muslim in China

Joe Mackertich was able to pass for a day as a Xinjiang migrant in Shanghai. His appalling treatment goes to show why Uighurs rioted over the weekend

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

China's Xinjiang province was rocked by riots over the weekend which resulted in the deaths of more than 140 people - the country's worst violence since the Tiananmen Square incident 20 years ago. The tragedy comes as no surprise to anybody familiar with Chinese society. The only surprise should be that it does not happen more often.

Enormous, landlocked Xinjiang has only been part of China for 115 years, and it is one of the most volatile regions in Asia. As far as most Chinese are concerned, the northwest region is at the end of the civilised world - the place where the dilapidated tail of the Great Wall disappears into the sand. It is also a place of barbarism, un-Chinese values and danger.

Wen Ding is a Chinese national living in the UK who spent years of her childhood travelling back and forth to Xinjiang with her father, a Beijing newspaper editor. "It was so scary walking in the street," she says of Urumqi, Xinjiang's capital. "Me and my dad both felt really unwelcome. The people seemed dangerous."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

As I had dark hair and a full beard, I could briefly pass myself off as Uighur Such views on Xinjiang abound in mainland China. Ask a random Han Chinese about the Uighurs (Xinjiang's Muslim ethnic majority) and you will almost certainly learn that: (one) they sell drugs, (two) they carry concealed weapons and (three) they find it easy - even enjoyable - to kill people.

I experienced this blatant, ugly racism at first hand while living in Shanghai, after I made friends with two bakers who had recently arrived from Xinjiang to flog hot Uighur bread outside a restaurant. One of them spoke Chinese and he insisted that, as I had full dark hair and a full beard, I could briefly pass myself off as Uighur and find out how badly they were treated by Han Chinese.

Dutifully I put on a traditional Xinjiang hat, called a doppa, and got to work selling bread. Most of the customers didn't seem to notice my Western features - evidently a beard and an ethnic hat is enough to go undercover as a minority in China. People were certainly brisker with me than when I introduced myself as British. At one point a man on a bicycle stopped and pointed at me. "That is a Muslim," he said proudly to his girlfriend, sat on the back. Worse was to come. The next day I went to an open-air bazaar next to the Xinjiang bakery to buy presents for my family. One of the stalls was run by a woman who had evidently seen me during my stint as a Xinjiang baker. When I tried to buy one of her worthless trinkets she looked away and said: "We don't sell to you people here."

These attitudes and the racist stereotypes that inspire them have been conjured up - not by fishermen's wives - but by the fevered imaginations of the government's Ministry of Propaganda. The Communist Party prefers its citizens to live in a constant state of fear, and when Japan is unavailable to use as a scapegoat, the government resorts to Xinjiang. Chinese newspapers often carry stories of Han Chinese citizens mugged or murdered by crazed 'Uighur separatists' or 'extremists'.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

There are grains of truth at the heart of some of these ugly stereotypes. Uighurs are often running the (very small) illegal drug markets inside Chinese cities. However, like the Jews of 14th-century Florence who turned to banking because they were not permitted to do anything else, Uighur job prospects outside of Xinjiang are all but limited to chef or sultana salesman. Selling dope to Shanghai's European and American expats is a tempting and lucrative proposition. One of the reasons that the Uighurs are discriminated against in this way is because they do not usually look Chinese. Their facial features are more similar to those found in central Asia, Turkey, even Russia. Uighur cooking and fashion too, is a world away from anything found in Shanghai or Beijing. The language is closer to Uzbek than it is to Mandarin Chinese.

During the dark years of the Cultural Revolution, this distinct Xinjiang culture was suppressed in predictably brutal fashion. The government was paranoid about losing control of the distant region and made up for it by cracking down extra-hard on all forms of non-Communist activity.

Mosques were smashed, religious clothing banned and indigenous languages outlawed. Under Mao, Xinjiang's economy was managed so badly that in the 1960s up to 60,000 citizens fled the country into Soviet Russia to escape a living hell. These injustices, combined with a 1949 promise of full autonomy for the Uighurs that was never fulfilled, continue to fuel the tension that has erupted so violently in recent days. In the 21st century Uighurs are officially allowed religious freedom but it doesn't take a degree in sociology to see that a marriage of Islamic belief and Communist law is never going to be a happy one.

Furthermore, with Han Chinese workers today being offered generous incentives to relocate to Xinjiang, the Uighurs, like the Tibetans, are increasingly being treated like second-class citizens in their own home.

It should be obvious that these people are understandably angry and entirely indifferent to the Communist cause. We can expect the bloodshed to continue.

EDITOR"S NOTE: Since this article was posted, the death toll in Urumqi, capital of Xinjiang province, has risen to 156, according to official reports, and more than 1,400 people have been arrested for taking part in riots on Sunday. The arrests brought further street protests on Tuesday, mainly by Uighur women complaining their men had been arbitrarily held by police.

is a journalist and copyrighter who lives in London. He writes mainly about Chinese, American and Iranian politics. He learned Mandarin Chinese while working in Jiangsu province. As well as The First Post, he has written for the New Statesman, the Observer, and the Times. He also regularly appears on Press TV, an Iranian news channel.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

How corrupt is the UK?

How corrupt is the UK?The Explainer Decline in standards ‘risks becoming a defining feature of our political culture’ as Britain falls to lowest ever score on global index

-

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?In the Spotlight Mass closure of shops and influx of organised crime are fuelling voter anger, and offer an opening for Reform UK

-

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?Today’s Big Question Nigel Farage’s party is ahead in the polls but still falls well short of a Commons majority, while Conservatives are still losing MPs to Reform

-

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strong

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strongTalking Point Party is on track for a fifth consecutive victory in May’s Holyrood election, despite controversies and plummeting support

-

What difference will the 'historic' UK-Germany treaty make?

What difference will the 'historic' UK-Germany treaty make?Today's Big Question Europe's two biggest economies sign first treaty since WWII, underscoring 'triangle alliance' with France amid growing Russian threat and US distance

-

Is the G7 still relevant?

Is the G7 still relevant?Talking Point Donald Trump's early departure cast a shadow over this week's meeting of the world's major democracies

-

Angela Rayner: Labour's next leader?

Angela Rayner: Labour's next leader?Today's Big Question A leaked memo has sparked speculation that the deputy PM is positioning herself as the left-of-centre alternative to Keir Starmer