What do the Democrats stand for?

America is effectively a 2-party system. Here's a look at the older party.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It did not take long for the young United States to develop into a two-party democracy, much to the chagrin of some of its founders. And since 1860, those two parties have been the Democratic Party and the Republican Party.

The Democratic Party is older, officially founded in 1844 but with origins in President Andrew Jackson's 1824 campaign and roots in — and here's where it gets a little confusing — Thomas Jefferson's Republican Party, later called the Democratic-Republican Party.

The party's ideology and views on government, business and social issues have changed dramatically over the past 200 years. Here's a look at what today's Democratic Party stands for, plus a little history of how they got here.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What do today's Democrats stand for?

Democrats want to create a "land of more freedom" and "more rights" and an economy "where everyone has a fair shot at getting ahead," the party said in its 2024 platform. Other listed goals include protecting communities, tackling the "scourge of gun violence" and the "climate crisis," restor[ing] the "right to choose" reproductive care and "lower[ing] the temperature in our politics" so democracy can thrive.

Overall, the Democrats are the more socially and economically liberal of America's two parties and generally favor enforced rights for racial and ethnic minorities, women, LGBTQ+ people, abortion access and collective bargaining by workers.

There is ideological diversity in the Democratic Party — its congressional delegate includes the leftist "Squad" and more the moderate-conservative Blue Dog faction. But most Democrats favor government intervention to expand voting access, fight environmental degradation and climate change, and enforce stricter gun laws. Democrats also support progressive taxation, where wealthier people pay a higher share of their income to the federal government.

Today's national Democratic Party cites as key accomplishments the 19th amendment, which gave women the right to vote; President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal programs, including Social Security, the G.I. Bill and electrifying rural America; President John F. Kennedy's moonshot; the Voting Rights Act and Civil Rights Act of 1964 under President Lyndon B. Johnson; and President Barack Obama's Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare. Under President Joe Biden, Democrats enacted sizable investments in infrastructure and clean energy.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How are Democrats different than Republicans?

For the past half century, at least between the election of President Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump's heterodox presidency, the Republican Party has generally favored robust military spending and been willing to use the military to conduct foreign policy; opposed most other government spending; strived to cut federal taxes across the board but especially for businesses and wealthy individuals on the theory that prosperity would trickle downward; fought for expanded individual gun rights and looser federal regulations; and pursued conservative social policies on sexual, moral and religious issues.

Democrats tend to get elected in larger cities, while Republicans have been increasingly planting their flag in parts of rural America. The suburbs and exurbs are contested territory.

How have the Democratic Party's positions changed over the years?

The Jacksonian Democrats of the 1820s, up through the end of President Grover Cleveland's terms in 1897, were "basically conservative and agrarian-oriented, opposing the interests of big business" and skeptical of big government, Britannica said. By the time FDR was re-elected in 1936 on his big-government New Deal accomplishments, the Democrats had "forged a broad coalition — including small farmers, Northern city dwellers, organized labor, European immigrants, liberals, intellectuals and reformers."

It's hard to pinpoint exactly when that switch happened in the Democratic Party, much less why, U.C. Davis history professor Eric Rauchway said at the blog Edge of the American West. But it happened "sometime between, let's say, 1872 and 1936" — after Democratic nominee William Jennings Bryan's unsuccessful campaign "emphasized the importance of social justice in the priorities of the federal government," and before FDR expanded on and successfully implemented those ideas.

Probably the largest shift was on race, however. Southern Democrats were the largest supporters of allowing slavery before the Civil War and opposed voting, civil and other rights for Black people long after the war ended. The Republican Party, meanwhile, opposed slavery, and early Republican presidents emancipated enslaved Americans and enforced their new civil rights in the South during Reconstruction.

That began to shift in the mid-20th century. When Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 at Johnson's urging, 69% of his fellow Democrats in the Senate voted for it along with 82% of Republican senators. "I think we just delivered the South to the Republican Party for a long time to come," Johnson reportedly said to aide Bill Moyers after signing the bill, per History.com. His successor, Republican President Richard Nixon, courted disaffected Southern Democrats, and many Southern lawmakers (and voters) did switch to the GOP. A Republican-heavy Supreme Court dismantled much of Johnson's Voting Rights Act in the 21st century.

What's with the donkey and the color blue?

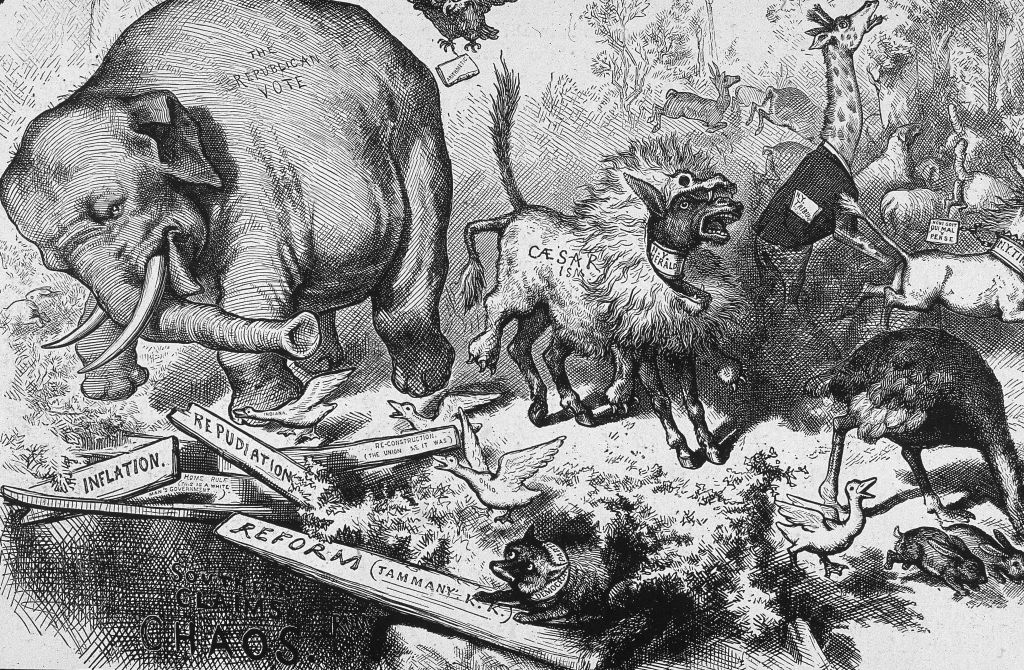

The donkey has been associated with the Democratic Party ever since Andrew Jackson's 1828 campaign, when Jackson embraced the "jackass" sobriquet thrown at him by his less-populist rivals. But it was hugely influential political cartoonist Thomas Nast who made the donkey symbol stick, starting in 1870 but most notably with his 1874 cartoon "Third Term Panic," which also popularized the elephant as the symbol for Nash's own Republican Party.

Republicans adopted the elephant as their official symbol, "and although the Democrats have yet to declare their own, you wouldn't need to walk more than a couple paces at one of their rallies before spotting a donkey," CNN reported. "It's a little weird that both of the major American political parties have embraced their mascots so enthusiastically, considering how poorly the two animals come across in Nast's original cartoons: how stupid, how pliable, how easily confused. Maybe neither party bothered to check before stocking up on pins and tote bags." Or maybe they embraced the self-mockery.

Democrats have officially adopted blue as their color, but the idea came from election night network news broadcasts. Until the prolonged 2000 presidential election results standoff, there was no uniformity in which color was assigned to states won by the Democratic and Republican candidates on the electoral map. It was the U.S. Supreme Court that tipped the 2000 election to President George W. Bush, but it was news networks that decided that year that Republicans are red and Democrats are blue.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

Political cartoons for February 12

Political cartoons for February 12Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include a Pam Bondi performance, Ghislaine Maxwell on tour, and ICE detention facilities

-

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ return

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ returnThe Week Recommends Carrie Cracknell’s revival at the Old Vic ‘grips like a thriller’

-

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ film

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ filmThe Week Recommends Akinola Davies Jr’s touching and ‘tender’ tale of two brothers in 1990s Nigeria

-

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ video

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ videoSpeed Read The jury refused to indict Democratic lawmakers for a video in which they urged military members to resist illegal orders

-

The UK expands its Hong Kong visa scheme

The UK expands its Hong Kong visa schemeThe Explainer Around 26,000 additional arrivals expected in the UK as government widens eligibility in response to crackdown on rights in former colony

-

‘Hong Kong is stable because it has been muzzled’

‘Hong Kong is stable because it has been muzzled’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seat

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seatSpeed Read Christian Menefee won the special election for an open House seat in the Houston area

-

Will Peter Mandelson and Andrew testify to US Congress?

Will Peter Mandelson and Andrew testify to US Congress?Today's Big Question Could political pressure overcome legal obstacles and force either man to give evidence over their relationship with Jeffrey Epstein?

-

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his health

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his healthIn Depth Some in the White House have claimed Trump has near-superhuman abilities