What do the Republicans stand for?

America is effectively a two-party system. Here's a look at the Party of Lincoln ... and Trump

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The United States has been a two-party democracy for most of its existence, much to the chagrin of some of its anti-partisan founders. Since 1860, those two parties have been the Democratic Party and the Republican Party.

The Republican Party emerged in 1854 from the embers of the anti-slavery movement and the ashes of the Whigs. After its 1856 nominee lost, the Republican Party made its presidential debut with Abraham Lincoln in the pivotal election of 1860. The Republicans then held the White House for most of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, up until Franklin D. Roosevelt's election in 1932.

The Party of Lincoln has changed a lot over the past 160 years. Here's a look at what today's Republican Party stands for, and a little history of how it got here.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What do today's Republicans stand for?

"Republicans believe in liberty, economic prosperity, preserving American values and traditions, and restoring the American dream for every citizen of this great nation," the Republican National Committee said, introducing its 2024 party platform, titled "Make America Great Again!" — the campaign slogan of party leader Donald Trump.

The Republican Party said that its legacy, being founded "for the purpose of ending slavery," compels it "to patriotically defend America's values" and "preserve America's greatness." A hallmark of Trump's Republican Party is a hardline stance against most immigration, especially across the southern border with Mexico. The 2024 platform commits to the "largest deportation program in American history."

Republicans have in recent decades pursued low taxes, especially for companies and for wealthy individuals whose tax burden is often higher. They are also for less federal regulation of the economy and environment. As a result of this anti-regulation stance, Republicans are typically proponents of certain individual rights, notably gun ownership. The party opposes affirmative action and most organized labor, and has a longstanding goal of trimming or eliminating government-funded social programs like Social Security and Medicare to reduce government spending. The GOP is more comfortable regulating the private, non-economic sphere, backing hard limits on abortion and LGBTQ rights. At a state level, Republicans have increasingly inserted Judeo-Christian prayer and iconography into public life.

The Republican Party has also pushed for robust military spending — though it was Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower who warned about the dangers of the "military-industrial complex" in 1961 — and has been more willing to pursue unilateral military action at the expense of international alliances. The 2024 platform promotes "peace through strength," a phrase associated with Republican President Ronald Reagan.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How are Republicans different than Democrats?

The Democratic Party aims to dedicate more federal resources to social and economic programs and building a more comprehensive safety net. That requires money, so Democrats favor collecting more tax revenue, especially from wealthy people and companies. Republicans traditionally believe the free market is a more efficient way to solve societal problems.

The Democratic Party is less economically libertarian than the Republican Party but tends to favor keeping the government out of personal decisions, notably when it comes to abortion access and sexual and gender issues.

In the past few decades, Republicans have come to dominate rural areas while Democrats have gained strength in larger cities and urban areas. The suburbs have become political battlegrounds that often decide which party wins Congress and the White House.

How have the Republican Party's positions changed over the years?

When the Republican Party was founded, it was not opposed to foreceful federal intervention in the economy or society — quite the opposite — and its power base was the urban northeast.

In the 1860s and 1870s, the Republicans enacted, "over Democratic opposition," a "highly ambitious program for expanding federal power," including aid for the transcontinental railroad, the state university system, the Homestead Act for Western settlers, and the civil rights of Black former slaves through the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 14th Amendment and creating of the Justice Department, said Eric Rauchway, a history professor at the University of California, Davis, in the Edge of the American West blog.

From the 1890s through the 1920s, both parties were "promising an augmented federal government devoted in various ways to the cause of social justice," but by the Calvin Coolidge administration, the Republican Party began to "sound like the modern Republican Party, rhetorically devoted to smaller government," Rauchway added. That "rhetorical tendency" was cemented in "the early 1930s and the era of Republican opposition to the New Deal."

It would take another decade or so, starting in World War II, for the Republicans to switch roles with the Democrats on civil rights for Black Americans. The party's 1952 platform already opposed federal civil rights legislation, and "many white Southerners began migrating to the GOP due to their opposition to big government, expanded labor unions and Democratic support for civil rights," History.com said. "Meanwhile, many Black voters, who had remained loyal to the Republican Party since the Civil War, began voting Democratic after the Depression and the New Deal." By the 1970s, the two parties had effectively traded places from where each had stood a century earlier.

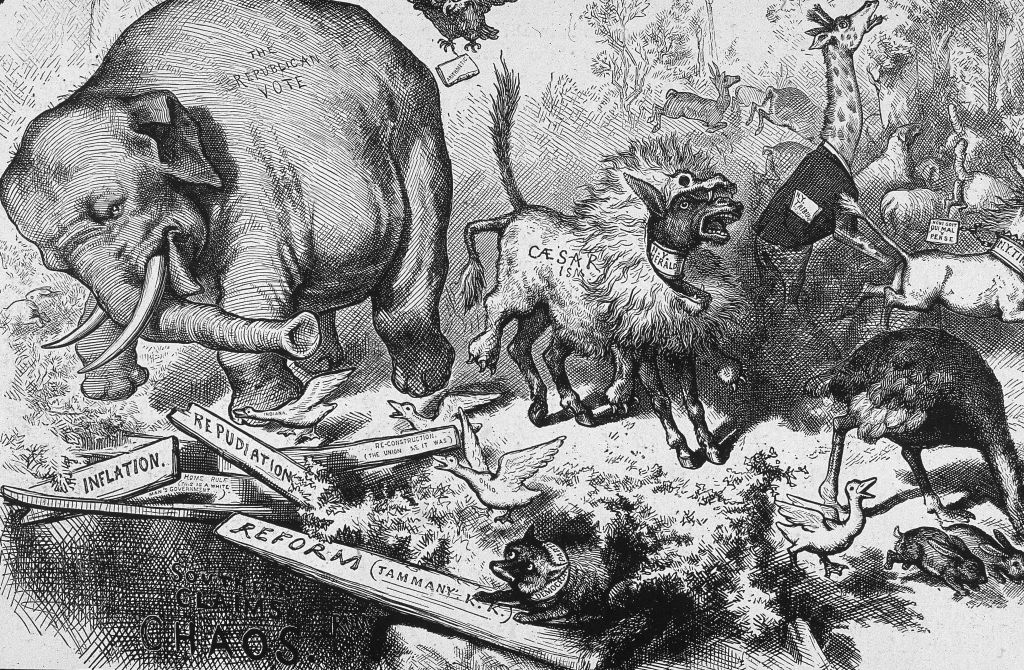

What's with the elephant and the color red?

The Republicans became associated with elephants — and gained their Grand Old Party (GOP) nickname — in the 1870s. Elephants had been used to depict Republicans in a 1864 Abraham Lincoln campaign newspaper and Harper's Weekly in 1872, Helen Kampion said in the National Children's Book and Literacy Alliance's Our White House blog. But it was influential political cartoonist Thomas Nast who sealed the idea of Republicans as elephants (and Democrats as donkeys) in an 1874 cartoon called "Third Term Panic," which warned about President Ulysses Grant's flirtation with a third term in office.

The first recorded Republican use of Grand Old Party was in 1874, when party officials in post–Civil War Minnesota boasted that "the grand old party that saved the country is still true to the principles that gave it birth," The Washington Post said. (Democrats had used "grand old party" to describe their much-older party in 1859 and 1860.) Some Republican publications experimented with Gallant Old Party in the 1880s, but use of the initials GOP as a placeholder for the Republican Party is actually attributed to a Cincinnati Gazette typesetter who ran out of space in an 1884 article and improvised.

Republicans have officially embraced red as their color, but the idea came from network news broadcasters who decided during the prolonged 2000 presidential election count that states won by Republican George W. Bush were red, and those won by Democrat Al Gore were blue.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’Feature A grim reaper for software services?

-

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC head

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC headSpeed Read Jay Bhattacharya, a critic of the CDC’s Covid-19 response, will now lead the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

-

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION As the Trump administration continues to try — and fail — at indicting its political enemies, Democratic lawmakers have begun seizing the moment for themselves

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ video

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ videoSpeed Read The jury refused to indict Democratic lawmakers for a video in which they urged military members to resist illegal orders

-

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seat

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seatSpeed Read Christian Menefee won the special election for an open House seat in the Houston area

-

Will Peter Mandelson and Andrew testify to US Congress?

Will Peter Mandelson and Andrew testify to US Congress?Today's Big Question Could political pressure overcome legal obstacles and force either man to give evidence over their relationship with Jeffrey Epstein?