Why the U.S. can't lead on punishing Russia's war crimes

America has spent 20 years undermining the International Criminal Court

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

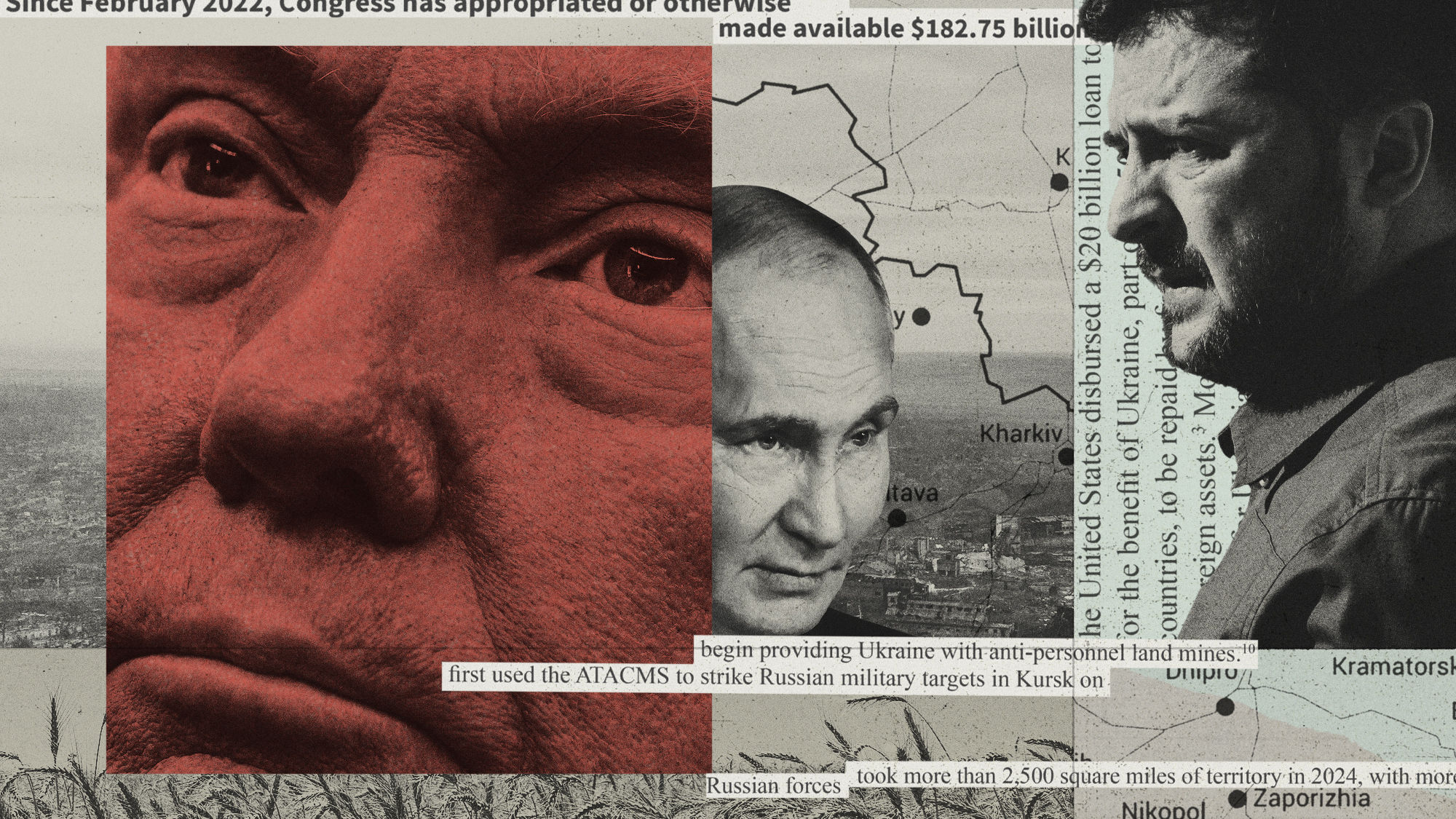

Vladimir Putin is a war criminal. That's not a strict legal judgment — not yet, at least — but the evidence keeps growing. Ukraine officials over the weekend said they had discovered a mass grave in the Kyiv suburb of Bucha, and journalists visiting the city described its streets as strewn with the bodies of civilians apparently executed by retreating Russian forces.

"This is genocide," Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said Sunday.

Outside observers are calling for prosecutions. Carla Del Ponte, a former war crimes prosecutor, over the weekend called for authorities to issue an international arrest warrant against Putin. That would probably be fine with the United States: President Biden has also called the Russian leader a "war criminal," and Secretary of State Anthony Blinken followed up last month with the announcement that the American government has formally determined that "members of Russia's forces have committed war crimes in Ukraine."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"As with any alleged crime," Blinken said in the official statement, "a court of law with jurisdiction over the crime is ultimately responsible for determining criminal guilt in specific cases."

The U.S., though, is ill-positioned to help bring about that justice — not without cloaking itself in immense hypocrisy, at any rate.

American leaders have spent the last two decades undermining the International Criminal Court, which prosecutes war crimes, genocide, and other crimes against humanity. The U.S. has used intimidation, sanctions and the heft of its hegemonic power to guarantee that none of its soldiers or officials will ever be brought before the court, no matter how deserving they might be.

"The United States is the number one advocate of international criminal justice for others," Princeton University's Richard Falk wrote in 2012. But the U.S. also "holds itself self-righteously aloof from accountability."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

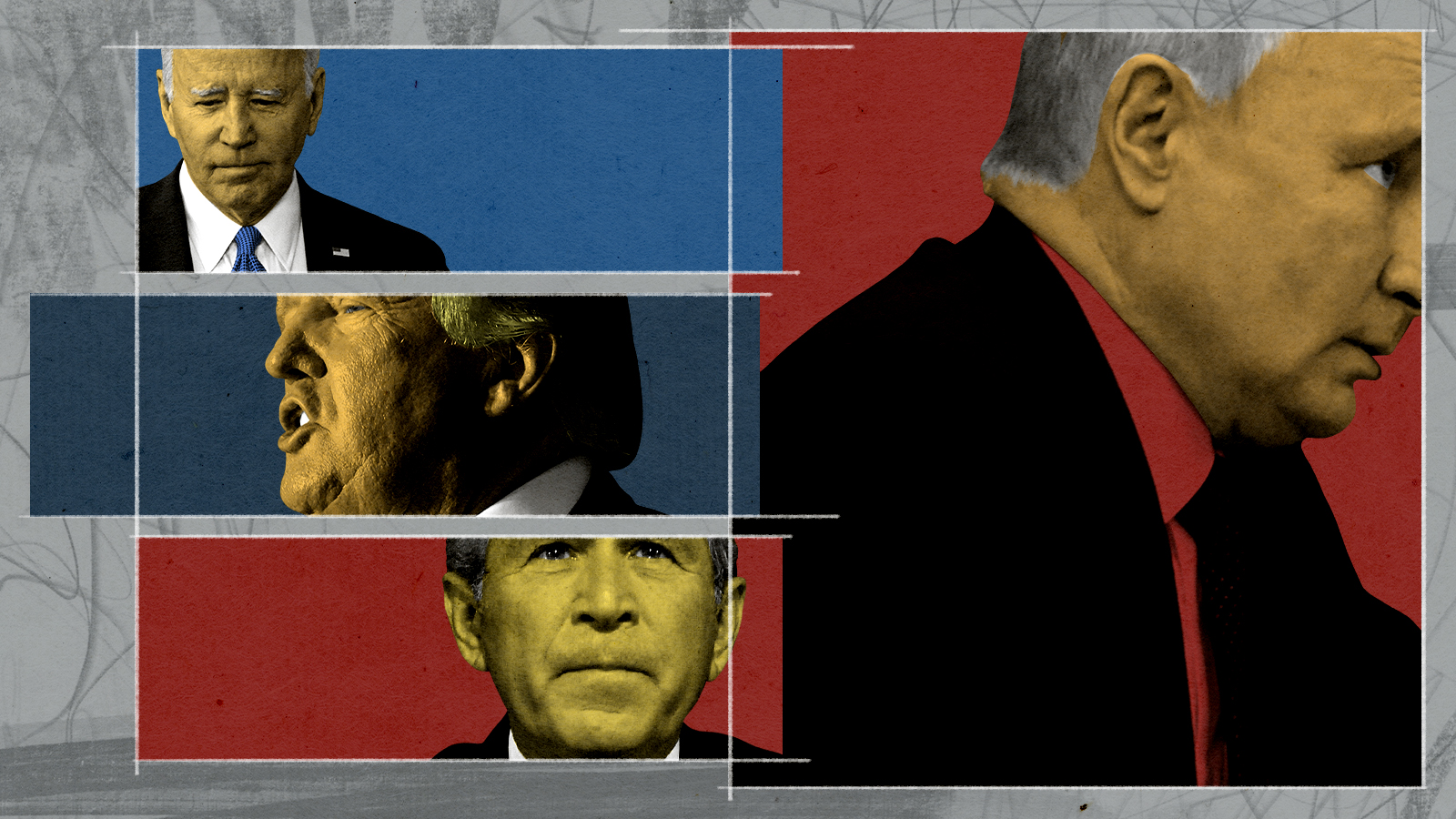

A short history: The U.S. under President Bill Clinton was initially a signatory to the treaty that created the court. "We do so to reaffirm our strong support for international accountability and for bringing to justice perpetrators of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity," Clinton said on his way out of office in 2000. "We do so as well because we wish to remain engaged in making the ICC an instrument of impartial and effective justice in the years to come."

That didn't happen. The treaty was never submitted to Congress.

And in 2002, President George W. Bush — who was already contemplating an invasion of Iraq — "unsigned" the treaty, saying the U.S. would not submit to the ICC's jurisdiction or submit to its orders. But the U.S. didn't just go absent from the treaty: Later that year, Bush signed the American Service-Members Protection Act, which made it illegal for U.S. authorities to cooperate with the court in any way — and which authorized "all means necessary and appropriate" to rescue any American or allied official from the court's clutches, if it ever came to that. Human Rights Watch dubbed the law the "Hague Invasion Act."

Even that wasn't enough impunity. In 2020, the Trump administration levied sanctions against ICC prosecutors. The Biden administration later reversed the measures, but the message was sent: Don't even think about investigating or charging Americans with war crimes. The message was clearly received.

There has been plenty to investigate. The ICC's existence has coincided almost precisely with America's "forever war" era. During the last 20 years, the U.S. has launched an unprovoked war of aggression against Iraq; tortured prisoners at Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo Bay and black sites around Europe; bombed civilians in Syria; and committed countless other acts worthy of scrutiny. Accountability has been rare. Gina Haspel ordered the destruction of evidence of torture and then was named CIA director. Others received pardons and were transformed into heroes for the Fox News set. We haven't always been the good guys.

Opponents of the ICC have claimed the institution interferes with American sovereignty, and that the ICC's trial process has insufficient protections for the accused. Mostly, though, it's difficult to escape the sense that America won't submit to the court's jurisdiction simply because it doesn't have to. What's the point of being the most powerful country on the planet if you have to follow the world's rules? The ICC is for other, smaller, weaker countries.

None of this justifies Putin's actions, of course. But it does suggest that America is seeking a kind justice to which it won't itself submit. And that means the U.S. — which has otherwise done an excellent job of managing the present crisis — can't provide much leadership in the matter of Russia's alleged war crimes against Ukraine.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surge

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surgeIN THE SPOTLIGHT Mass arrests and chaotic administration have pushed Twin Cities courts to the brink as lawyers and judges alike struggle to keep pace with ICE’s activity

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax

-

‘The West needs people’

‘The West needs people’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The mission to demine Ukraine

The mission to demine UkraineThe Explainer An estimated quarter of the nation – an area the size of England – is contaminated with landmines and unexploded shells from the war

-

The secret lives of Russian saboteurs

The secret lives of Russian saboteursUnder The Radar Moscow is recruiting criminal agents to sow chaos and fear among its enemies

-

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?Today's Big Question PM's proposal for UK/French-led peacekeeping force in Ukraine provokes 'hostility' in Moscow and 'derision' in Washington

-

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?Today's Big Question 'Extraordinary pivot' by US president – driven by personal, ideological and strategic factors – has 'upended decades of hawkish foreign policy toward Russia'

-

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?Today's Big Question US president 'blindsides' European and UK leaders, indicating Ukraine must concede seized territory and forget about Nato membership

-

Ukraine's disappearing army

Ukraine's disappearing armyUnder the Radar Every day unwilling conscripts and disillusioned veterans are fleeing the front

-

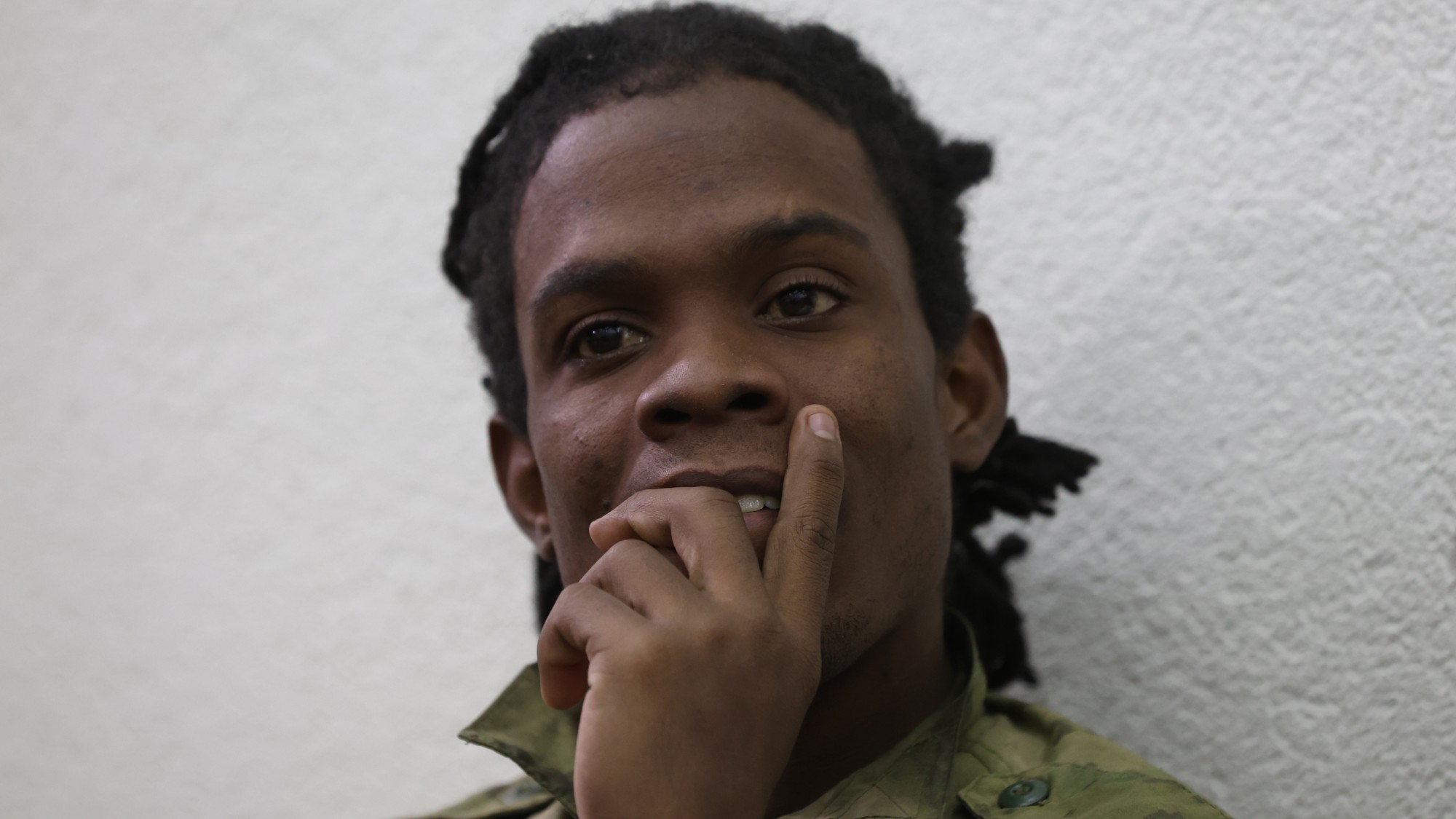

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against Ukraine

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against UkraineThe Explainer Young men lured by high salaries and Russian citizenship to enlist for a year are now trapped on front lines of war indefinitely

-

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?Today's Big Question Putin changes doctrine to lower threshold for atomic weapons after Ukraine strikes with Western missiles