Russia's war crimes were inevitable

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

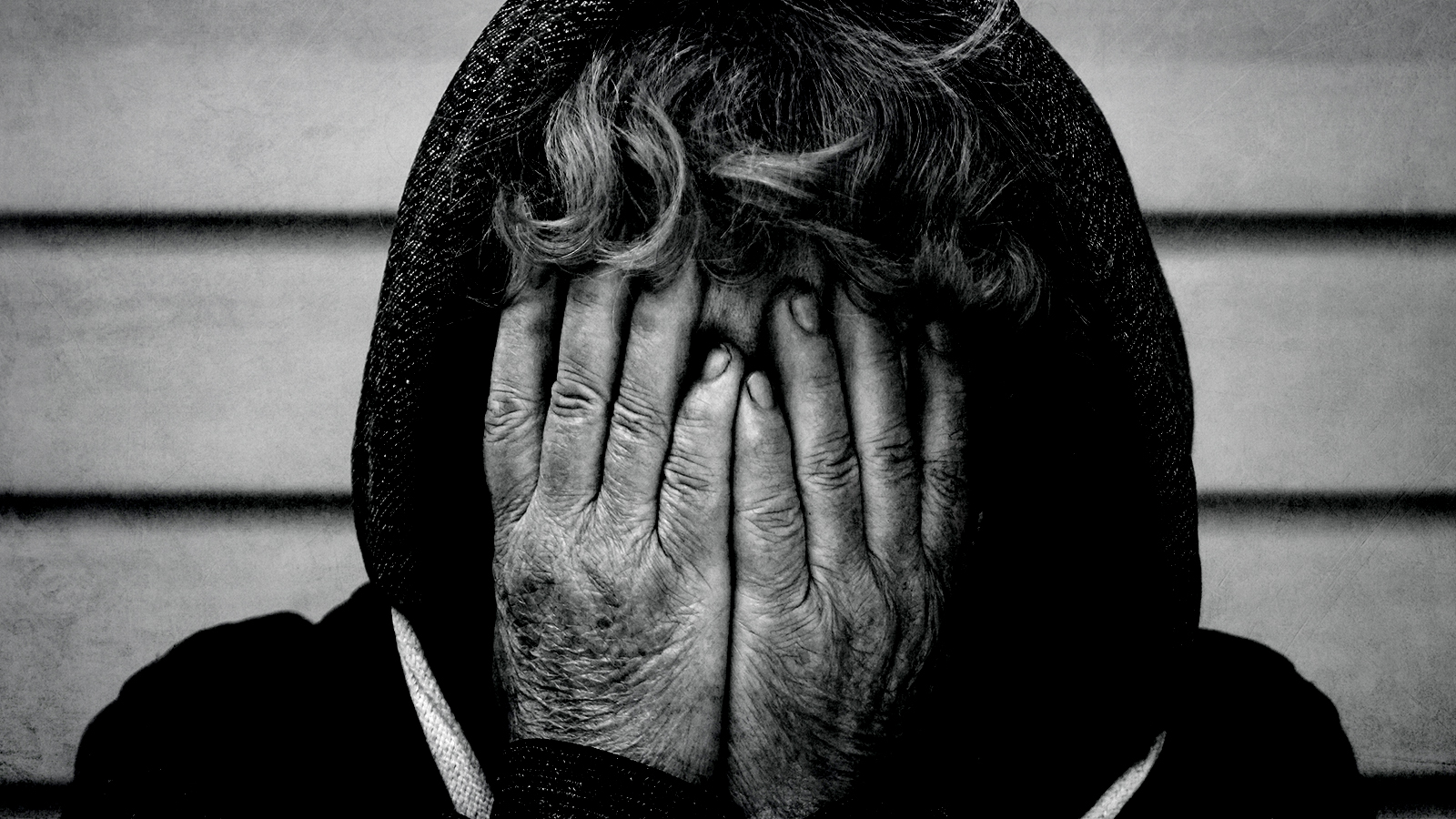

The tricky thing about discussing wartime atrocities is that war itself is atrocious. Bloody death is part of the deal already, but some of that violence is particularly offensive to us. So it goes with Russia's war in Ukraine.

The discovery of a mass grave and apparent civilian executions in Bucha, Ukraine has set off a new debate — actually, a fairly old one — about why such outrages occur. Is the Russian Army uniquely evil or undisciplined? Or were the war crimes the point, deliberately inflicted to sow terror among the Ukrainian survivors?

Or maybe the answer is all of the above?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

At Foreign Policy, the historian Bret Devereaux points out the Russians have a history of violence against civilian populations in Syria and Ukraine. Russia, he says, "had built an atrocity-prone military that it then unleashed on Ukraine."

"As can now be seen in places like Bucha," Devereaux writes, "the callousness of Russian leadership toward civilian deaths has created the same kind of permission structure, leading to escalating brutality against civilians by Russian soldiers even in areas under Russian control."

But "permission structures" are embedded even in armies proudly devoted to protecting civilians from harm. America is less than a year removed from a drone strike that massacred an innocent Afghan family, an atrocity that officials decided was "not unreasonable." That's a permission structure. And the essence of military training involves teaching young men and women to ignore deeply held moral precepts against killing other human beings. That's a permission structure, too, even if it's one that most countries deem a necessity for national defense.

In the best cases, such violence is supposed to be done under rigorous rules about which targets are permissible and which (civilians, generally) are not. Once the fighting starts, though, the lines can get fuzzy. A 2007 survey of U.S. Marines and Army troops in Iraq found that only a minority of both groups — 38 and 47 percent, respectively — thought civilians should be treated "with dignity and respect." It's unsurprising, then, when rigor goes out the window and innocent people are killed.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It's not just a war zone problem. The journalist Spencer Ackerman has documented how 20 years of war after 9/11 weakened American democracy. And the writer Robert Wright makes the case that even having a rooting interest in a war can harden our hearts against the violence and death involved. Once somebody is designated an "enemy," our usual standards of right and wrong begin to bend.

"The most basic prerequisite for committing an atrocity—assigning people to a category that removes them from moral concern—is something we've all done," Wright commented.

We should all be outraged by the atrocities in Bucha. But our righteous anger should be tempered with humility. Just about every armchair military expert is familiar with the aphorism that "war is the continuation of policy with other means." The means are violent and bloody, always. What we call "atrocities" and "war crimes" are just more of the horrifying same.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?Talking Point The Trump administration is applying the pressure, and with Latin America swinging to the right, Havana is becoming more ‘politically isolated’

-

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predators

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predatorsCartoons Artists take on the real victim, types of protection, and more

-

Palestine Action and the trouble with defining terrorism

Palestine Action and the trouble with defining terrorismIn the Spotlight The issues with proscribing the group ‘became apparent as soon as the police began putting it into practice’

-

The mission to demine Ukraine

The mission to demine UkraineThe Explainer An estimated quarter of the nation – an area the size of England – is contaminated with landmines and unexploded shells from the war

-

The secret lives of Russian saboteurs

The secret lives of Russian saboteursUnder The Radar Moscow is recruiting criminal agents to sow chaos and fear among its enemies

-

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?Today's Big Question PM's proposal for UK/French-led peacekeeping force in Ukraine provokes 'hostility' in Moscow and 'derision' in Washington

-

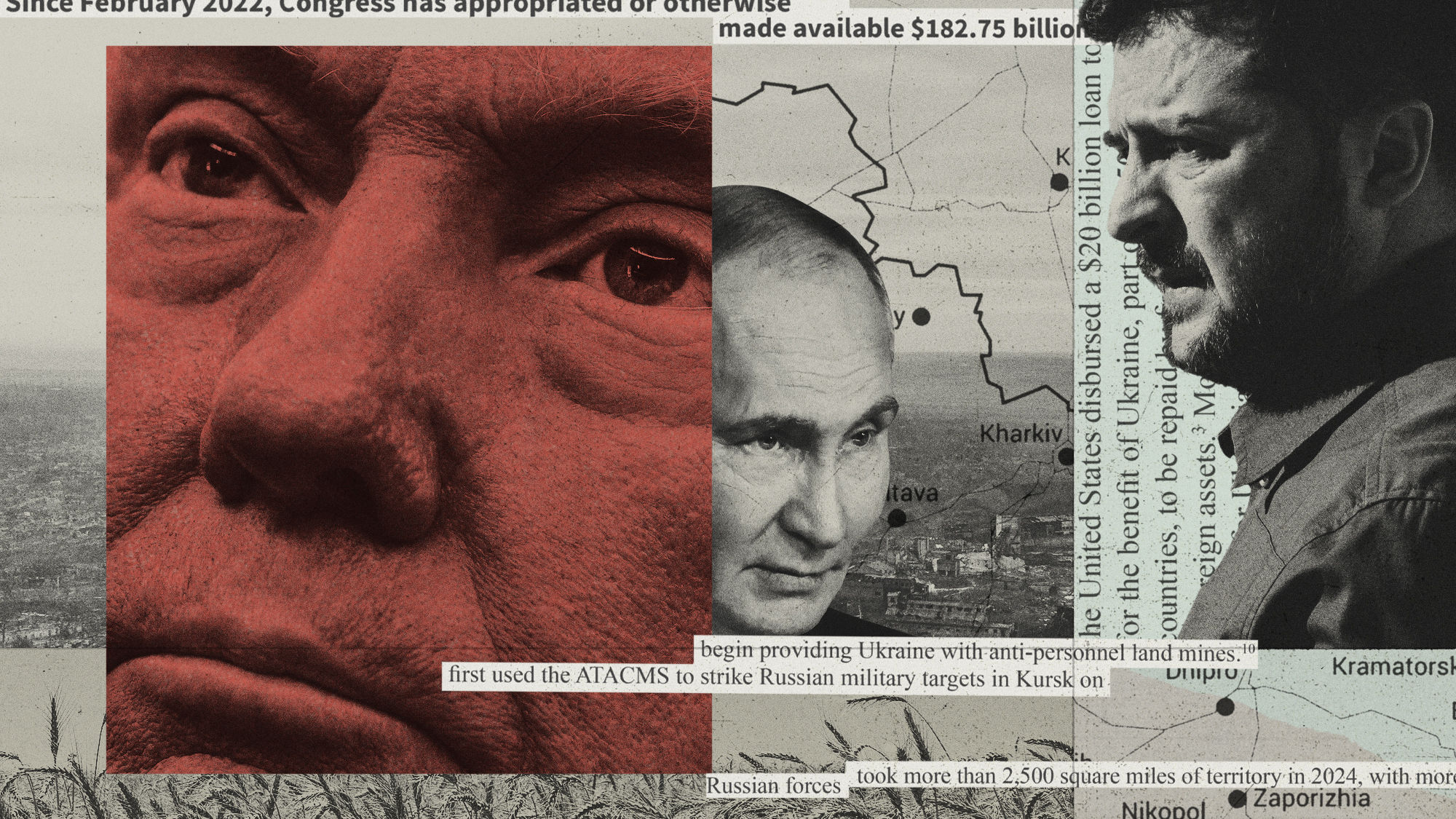

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?Today's Big Question 'Extraordinary pivot' by US president – driven by personal, ideological and strategic factors – has 'upended decades of hawkish foreign policy toward Russia'

-

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?Today's Big Question US president 'blindsides' European and UK leaders, indicating Ukraine must concede seized territory and forget about Nato membership

-

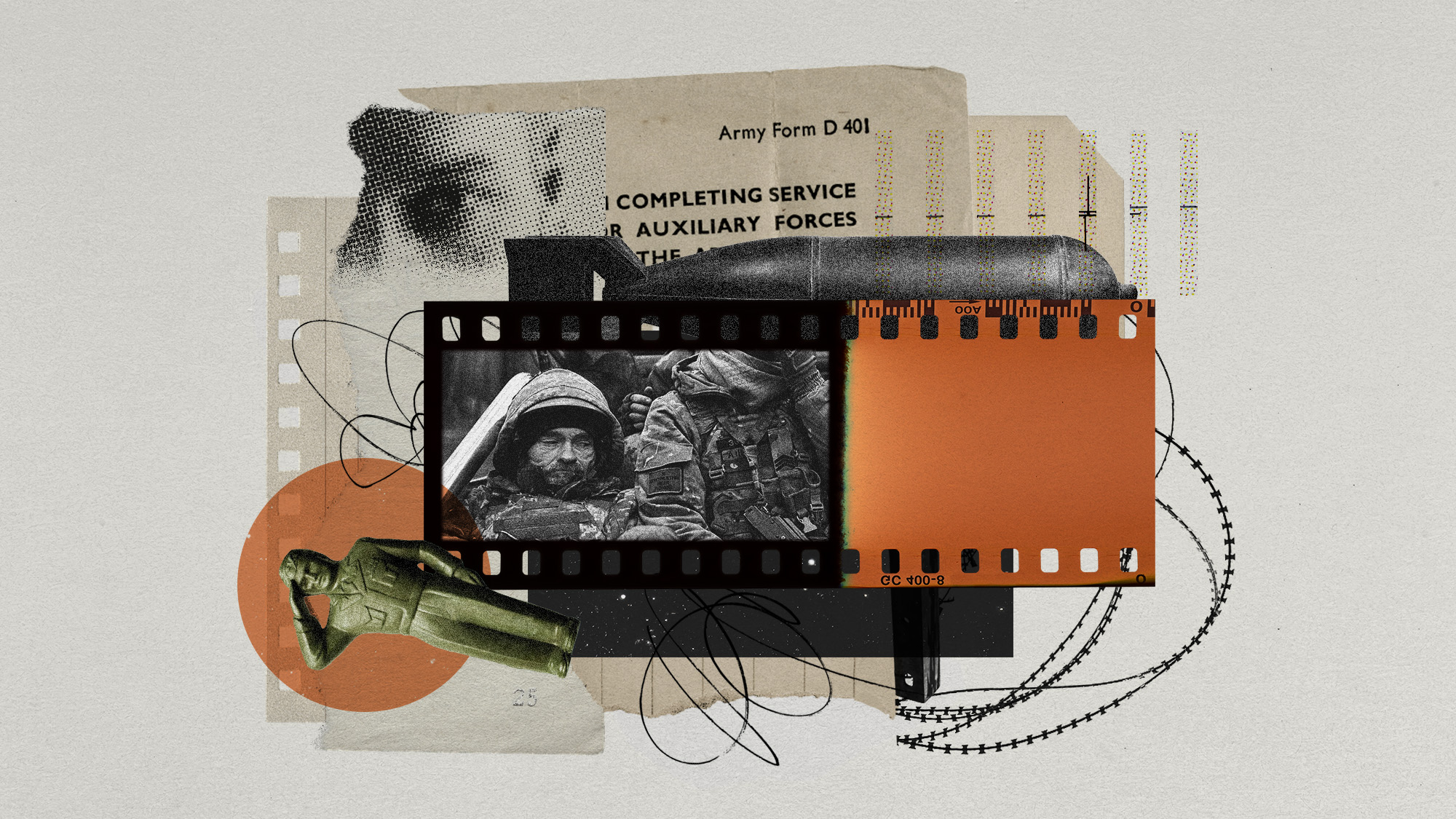

Ukraine's disappearing army

Ukraine's disappearing armyUnder the Radar Every day unwilling conscripts and disillusioned veterans are fleeing the front

-

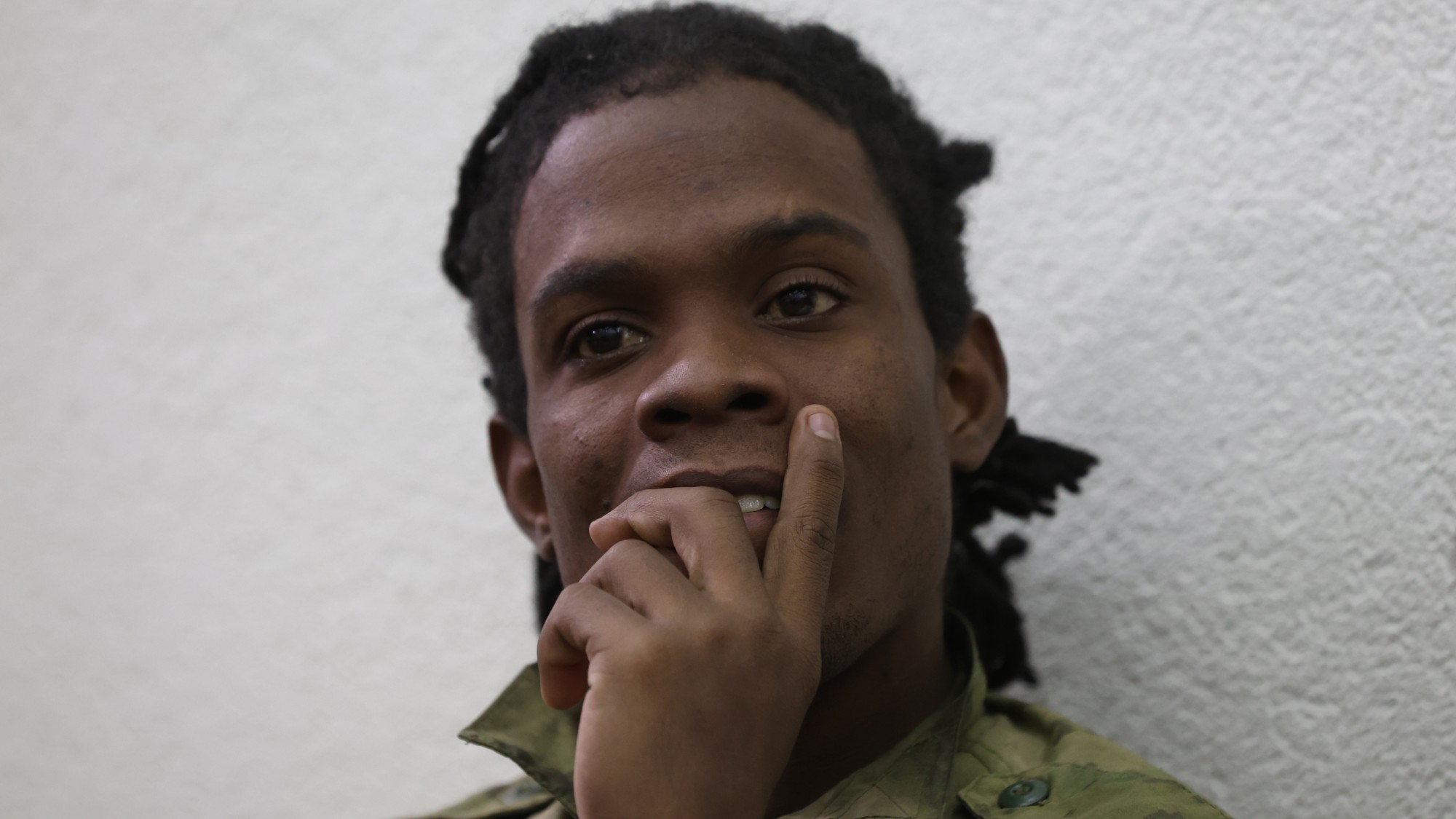

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against Ukraine

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against UkraineThe Explainer Young men lured by high salaries and Russian citizenship to enlist for a year are now trapped on front lines of war indefinitely

-

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?Today's Big Question Putin changes doctrine to lower threshold for atomic weapons after Ukraine strikes with Western missiles