Antimatter isn't immune to gravity, landmark experiment confirms

Antimatter is the mysterious evil twin of matter, but new research proves they do have something fundamental in common

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Antimatter — the mysterious substance that's the mirror opposite of matter in most ways — falls downward in gravity like everything else in the universe, a team of physicists reported Wednesday in the journal Nature. In a delicate, groundbreaking experiment conducted at the European Center for Nuclear Research (CERN), the scientists pretty conclusively proved that antiparticles are not governed by antigravity.

The results are a bit of a wet blanket for science fiction. "The bottom line is that there's no free lunch, and we're not going to be able to levitate using antimatter," study coauthor Joel Fajans of the University of California, Berkeley, told The New York Times. But they are kind of a relief for science. The tug of gravity on antimatter conforms with Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity. If the antiparticles had floated upward in the experiment, as some scientists had hypothesized, it would have turned the world of physics on its head.

"Antimatter is just the coolest, most mysterious stuff you can imagine," Jeffrey Hangst, the particle physicist whose 30 years of work trapping antiparticles led to the discovery, told BBC. "As far as we understand, you could build a universe just like ours with you and me made of just antimatter."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

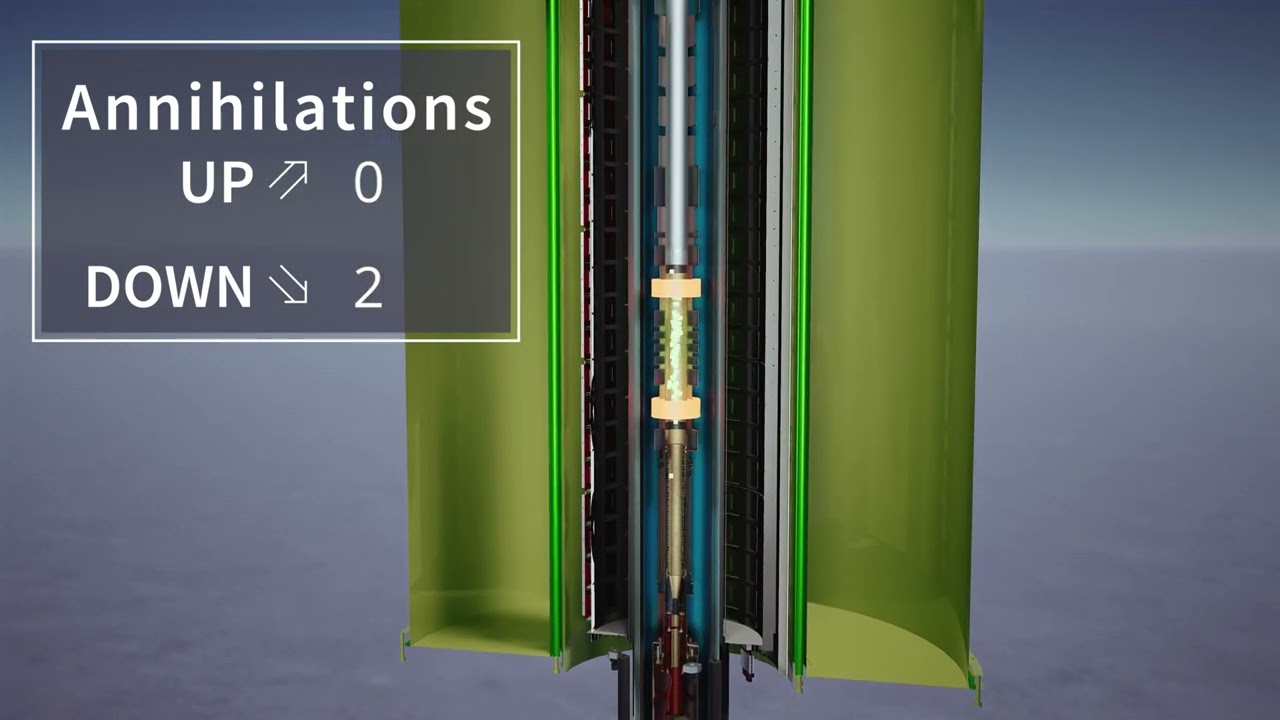

For this experiment, Fajans and his colleagues collected and suspended antihydrogen — the antimatter version of hydrogen, with one positively charged electron (positron) orbiting a negatively charged proton (antiproton) — in a magnetic field inside a specially designed tube. When the magnetic force was turned down on the top and bottom of the tube, some of the antiparticles rose but about 80% fell, roughly in line with hydrogen atoms.

The experiment left a bunch of huge questions about antimatter unanswered, however. The big one: Where is it?

When matter and antimatter meet, they annihilate each other in flashes of pure energy. Scientists believe that when the universe was born, the Big Bang created equal quantities of matter and antimatter. And they don't understand why matter won out while antimatter all but disappeared, only fleetingly observed in cosmic ray showers or created by colliding particles in labs like CERN.

One theory to explain what happened posited that all the antimatter was drawn away from the matter by antigravity and formed its own mirror antigravity universe. That hypothesis looks more implausible now.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

The ‘eclipse of the century’ is coming in 2027

The ‘eclipse of the century’ is coming in 2027Under the radar It will last for over 6 minutes

-

5 recent breakthroughs in biology

5 recent breakthroughs in biologyIn depth From ancient bacteria, to modern cures, to future research

-

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkiller

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkillerUnder the radar The process could be a solution to plastic pollution

-

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.Under the radar Humans may already have the genetic mechanism necessary

-

Is the world losing scientific innovation?

Is the world losing scientific innovation?Today's big question New research seems to be less exciting

-

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves baby

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves babyspeed read KJ Muldoon was healed from a rare genetic condition

-

Humans heal much slower than other mammals

Humans heal much slower than other mammalsSpeed Read Slower healing may have been an evolutionary trade-off when we shed fur for sweat glands

-

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brain

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brainSpeed Read Researchers have created the 'largest and most detailed wiring diagram of a mammalian brain to date,' said Nature