This BBC reporter warns that America's 'post-truth' media culture could savage Britain's democracy, too

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

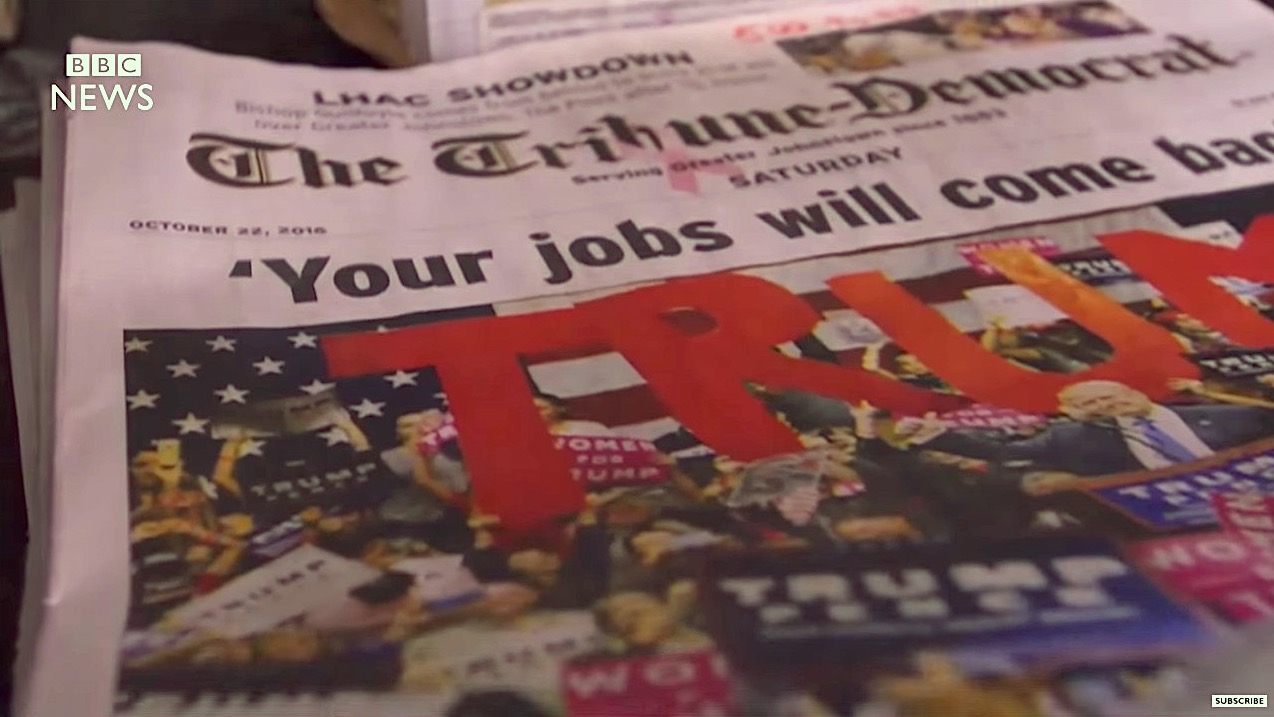

"How does America get its news? How does it know who or what to trust?" BBC special correspondent Allan Little asked in a year-end look at the fake-news phenomenon, pointing first to The Tribune-Democrat, of Johnstown, Pennsylvania: "You find conflicting opinions in its pages, a diversity of views. It offers its readers a shared public reality within which they can disagree, dispute, and challenge each other." This model doesn't appear to be thriving in the digital world, he adds. "Traditional journalism is losing its power to the internet and the echo chamber of social media. There are two Americas now, each listening to its own preferred news sources, two parallel public realities."

"Are there also now two Britains, each with their own parallel truths?" Little asked. He said no, "there is still a shared public reality in British politics, a common square where news is generated and consumed, but it's gone in America and it could go here, too. The dangers to democracy are obvious." In case they aren't, Little spoke to an expert on Russia, who argued that one of Vladimir Putin's masterstrokes was creating a news environment ruled by a fog of uncertainty, where the lack any common truth lets him govern as a strongman. "That's not great for democracy, is it?" Little asked. Still, democracies also value freedom of speech, he noted, so "who in the new media landscape is to police what's valid and what's fake, what's true and what's post-truth?"

It's a good question. Facebook? Advertising revenue? Anne Applebaum, in a first-person Washington Post account of being smeared by a Russian fake-news campaign, notes that this isn't the first time a new technology has been exploited to bad ends. "The printing press, praised by Martin Luther as 'God's highest and extremest act of Grace,' led to the Reformation, the Counter-Reformation — and a century of bloody religious wars," she writes. "The invention of radio led to Hitler and Stalin, who understood the new medium better than anyone else, as well as to the 20th century's totalitarian regimes and ideological wars."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Eventually, things settled down, and "someday we will reach equilibrium, too," she adds. "But until then we should be prepared for political turmoil of a kind we thought was long behind us." Read her column at The Washington Post for an intimate look at how Russia's disinformation apparatus works, and why American fell for it.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

Jeff Bezos: cutting the legs off The Washington Post

Jeff Bezos: cutting the legs off The Washington PostIn the Spotlight A stalwart of American journalism is a shadow of itself after swingeing cuts by its billionaire owner

-

5 blacked out cartoons about the Epstein file redactions

5 blacked out cartoons about the Epstein file redactionsCartoons Artists take on hidden identities, a censored presidential seal, and more

-

How Democrats are turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade

How Democrats are turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonadeTODAY’S BIG QUESTION As the Trump administration continues to try — and fail — at indicting its political enemies, Democratic lawmakers have begun seizing the moment for themselves

-

TikTok secures deal to remain in US

TikTok secures deal to remain in USSpeed Read ByteDance will form a US version of the popular video-sharing platform

-

Unemployment rate ticks up amid fall job losses

Unemployment rate ticks up amid fall job lossesSpeed Read Data released by the Commerce Department indicates ‘one of the weakest American labor markets in years’

-

US mints final penny after 232-year run

US mints final penny after 232-year runSpeed Read Production of the one-cent coin has ended

-

Warner Bros. explores sale amid Paramount bids

Warner Bros. explores sale amid Paramount bidsSpeed Read The media giant, home to HBO and DC Studios, has received interest from multiple buying parties

-

Gold tops $4K per ounce, signaling financial unease

Gold tops $4K per ounce, signaling financial uneaseSpeed Read Investors are worried about President Donald Trump’s trade war

-

Electronic Arts to go private in record $55B deal

Electronic Arts to go private in record $55B dealspeed read The video game giant is behind ‘The Sims’ and ‘Madden NFL’

-

New York court tosses Trump's $500M fraud fine

New York court tosses Trump's $500M fraud fineSpeed Read A divided appeals court threw out a hefty penalty against President Trump for fraudulently inflating his wealth

-

Trump said to seek government stake in Intel

Trump said to seek government stake in IntelSpeed Read The president and Intel CEO Lip-Bu Tan reportedly discussed the proposal at a recent meeting