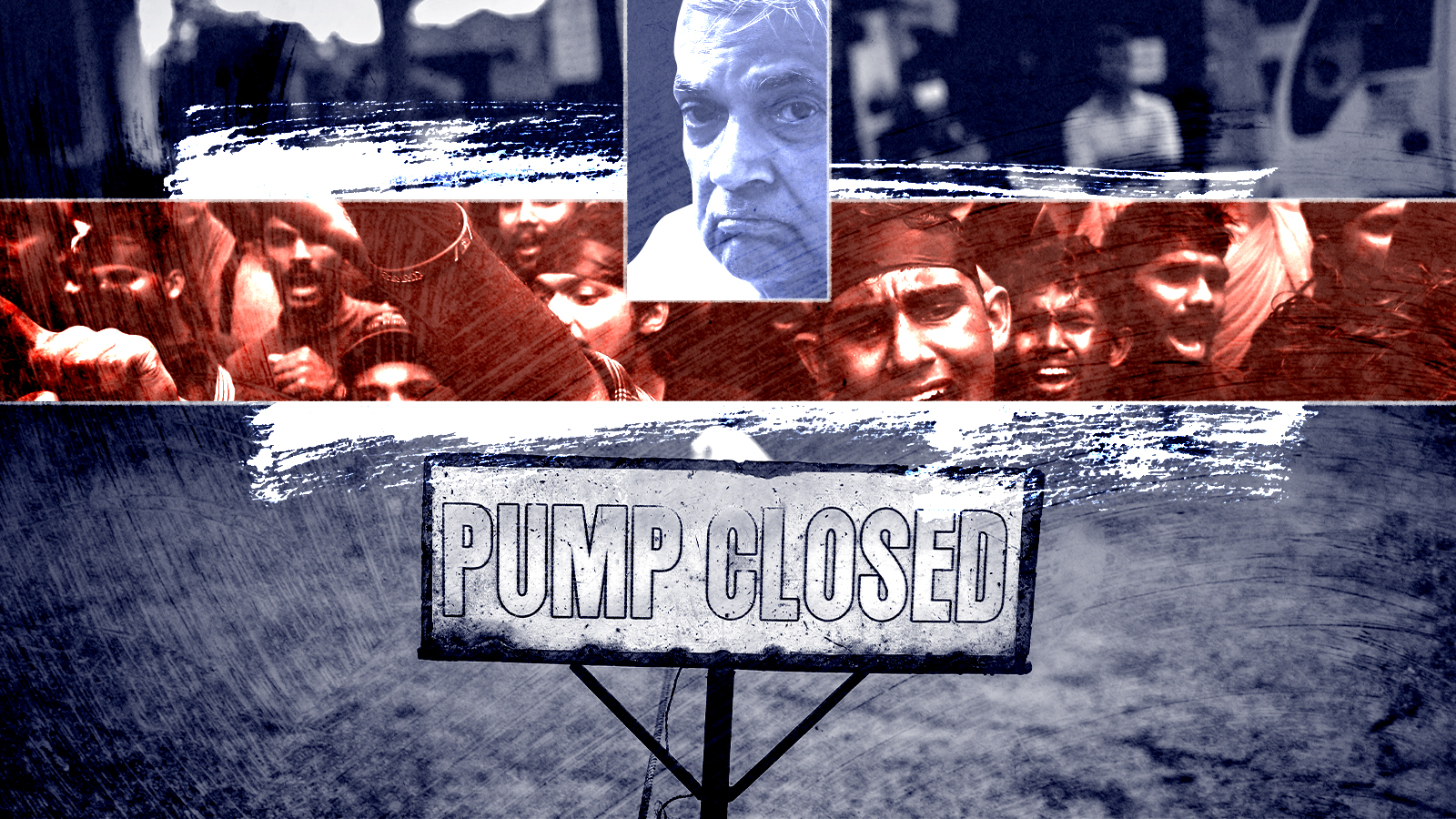

The Sri Lankan fuel crisis, explained

Protests, an unpopular dynasty, and economic downturn roil the South Asian nation

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On Monday, Sri Lanka's new prime minister, Ranil Wickremesinghe, warned that the South Asian country is almost out of gasoline and the "next couple of months will be the most difficult ones of our lives." This is just the latest crisis unfolding in Sri Lanka, where anti-government protesters are taking to the streets amid the worst economic downturn since Sri Lanka gained independence in 1948. Here's everything you need to know:

What triggered Sri Lanka's economic downturn?

Experts say this crisis didn't start overnight. Murtaza Jafferjee, chair of the Sri Lankan think tank Advocata Institute, told CNN that over the last 10 years, the government had to borrow massive amounts of money from foreign lenders to fund public services. At the same time, agriculture took a hit due to heavy monsoons and a government ban on chemical fertilizers. The COVID-19 pandemic compounded problems, and in an attempt to stimulate the economy, taxes were cut. This did more harm than good, with the government losing revenue and having to turn to its foreign exchange reserves to pay off its debt; in 2018, the reserves were at $6.9 billion, and that number has dropped to nearly zero today.

Why is there a gas shortage?

Most of the fuel in Sri Lanka is imported, and because of the country's economic crisis, there isn't enough money to pay for shipments; Wickremesinghe said on Monday. The government does not have even $5 million to import gasoline. Oil prices are also rising, making the situation more dire. There hasn't been cooking gas for several weeks, The New York Times reports, and gas stations keep having to turn customers away due to a lack of fuel.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

There are fuel ships anchored offshore, just waiting for the cargos to be paid for, and Wickremesinghe said an Indian credit line would be used to purchase two shipments of gasoline and two shipments of diesel. This will help alleviate the fuel shortage temporarily, but Wickremesinghe made it clear that the next few months "will be the most difficult ones of our lives. We must prepare ourselves to make some sacrifices and face the challenges of this period."

Why was Wickremesinghe appointed as prime minister?

The economic downturn has led to soaring inflation and shortages of foreign currency and essentials like food and medicine. Protesters began to make their way through the streets of Sri Lanka's capital, Colombo, in late March, calling on the government to do something about these issues. Most of the demonstrations were peaceful, but last week, backers of then-Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa stormed the main anti-government protest site, sparking days of violence between protesters, government supporters, and law enforcement, Al Jazeera reports.

Nine people were killed and more than 300 were injured, and in response, Mahinda Rajapaksa — whose house was burned down — resigned last Thursday. His brother, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, remains president, much to the dismay of protesters who want the Rajapaksa family out of politics. He appointed Wickremesinghe, an opposition parliamentarian, as the new prime minister. Many protesters consider Wickremesinghe — who has already served as prime minister five times before — one of the president's lackeys, and want a total overhaul of the government.

Is the Rajapaksa family a dynasty?

Members of the family have been major players in Sri Lanka's political scene for about two decades. Mahinda Rajapaksa was president from 2005 to 2015, during the time the Tamil Tiger insurgency was defeated, and then moved into the prime minister role when his brother Gotabaya Rajapaksa became president in 2019. "The Rajapaksa clan had its hands on various apparatuses of state, from exerting control over the security forces to commanding influence over major sectors of the economy," The Washington Post's Ishaan Tharoor writes.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Since the protests began, four members of the Rajapaksa family have stepped down from their government positions — Mahinda as prime minister; his son Namal as minister of sports and youth affairs; his brother Basil as minister of finance; and his brother Chamal as minister of irrigation. "Gotabaya is struggling to hold on politically," Tharoor writes, but experts believe economic recovery and help from the International Monetary Fund won't be possible while he's still in office. "The political situation has to be resolved before anything can happen," Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu, executive director of the Center for Policy Alternatives in Colombo, told the Post. "You need a credible government. The presidency right now is a poisoned chalice."

How is Wickremesinghe trying to turn things around?

Wickremesinghe is asking for $75 million in foreign funding within the next few days to pay for critical imports like food and medicine. He said on Monday that, if necessary, the central bank will print money to pay state employees. This would be "against my own wishes," Wickremesinghe said, adding, "we must remember that printing money leads to the depreciation of the rupee." He has also floated the idea of privatizing the state-owned Sri Lankan Airlines, which lost $129.5 million in the year ending in March 2021.

Catherine Garcia has worked as a senior writer at The Week since 2014. Her writing and reporting have appeared in Entertainment Weekly, The New York Times, Wirecutter, NBC News and "The Book of Jezebel," among others. She's a graduate of the University of Redlands and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Iran unleashes carnage on its own people

Iran unleashes carnage on its own peopleFeature Demonstrations began in late December as an economic protest

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Trump, Iran trade threats as protest deaths rise

Trump, Iran trade threats as protest deaths riseSpeed Read The death toll in Iran has surpassed 500