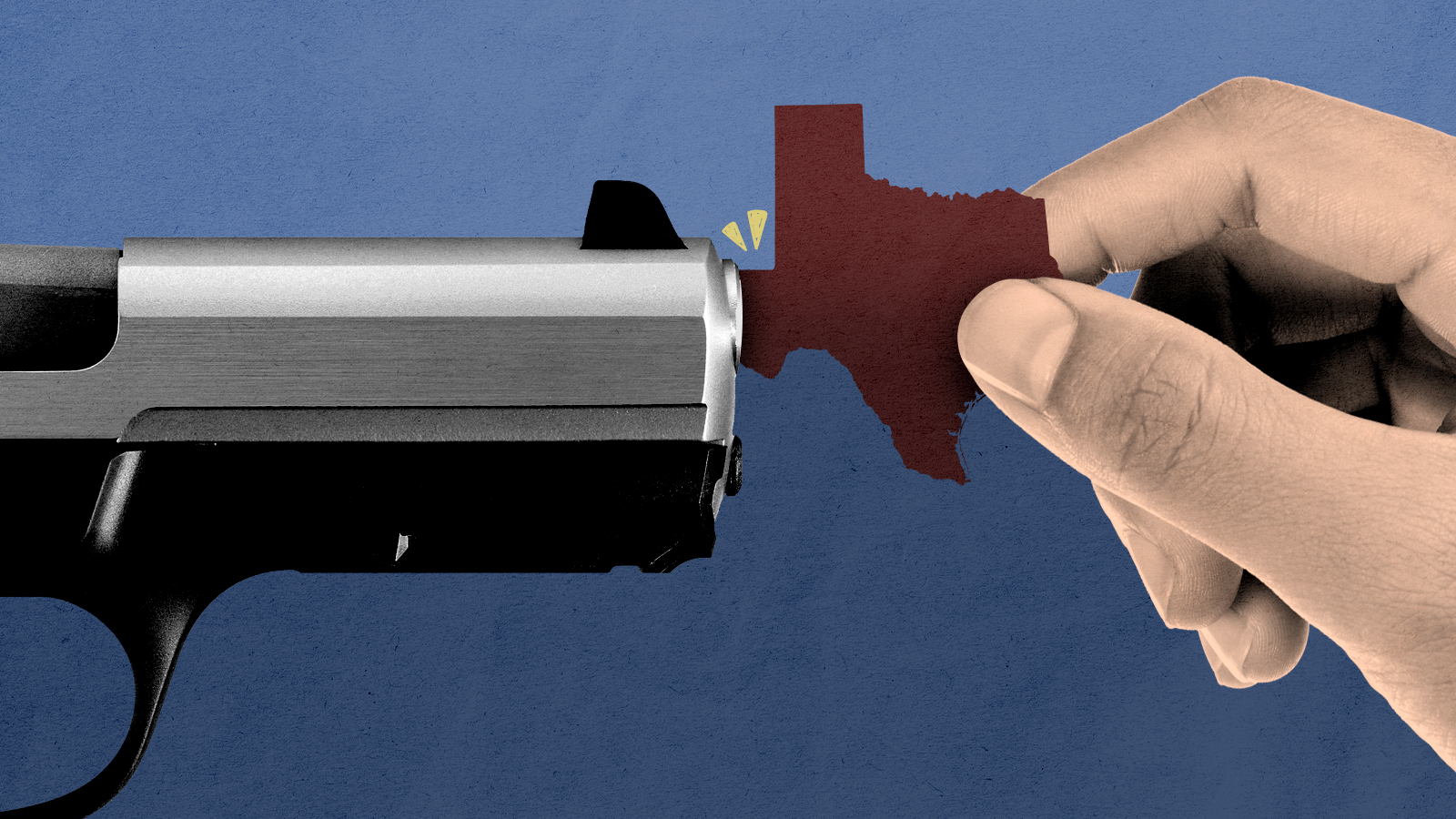

California shouldn't use Texas' abortion law as a guide

The Lone Star state's controversial law is a bad model for controlling gun violence

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It wasn't hard to see this coming: California Gov. Gavin Newsom on Saturday threatened to use Texas' unusual abortion law as a model for new gun restrictions in his own state.

"SCOTUS is letting private citizens in Texas sue to stop abortion?! If that's the precedent then we'll let Californians sue those who put ghost guns and assault weapons on our streets," Newsom, a Democrat, tweeted after the Supreme Court's decision on Friday to let the law remain in effect while abortion providers bring court challenges. "If TX can ban abortion and endanger lives, CA can ban deadly weapons of war and save lives."

Newsom's anger should be understandable, even if you're against abortion. The Texas law's enforcement mechanism — which encourages random private citizens to sue abortion providers in civil courts — is novel, alarming, and unjust. If the law is ultimately allowed to stand, it's likely that blue states will continue to be tempted to match red states with similar laws aimed at lefty hobbyhorses.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That would be disastrous, for several reasons.

Ideally, civil courts exist to fairly arbitrate and resolve disputes between citizens — usually a case in which one or both litigants has suffered some kind of injury or loss. The Texas law does something different: It uses those courts to create a new class of conflict, one in which a plaintiff is allowed to sue even if they have no relationship whatsoever to the persons either providing or receiving care. (Indeed, the first Texas lawsuit was brought by a former lawyer from Arkansas, more or less because he could.)

The law invites Americans to get up in each other's business. So, presumably, would Newsom's anti-gun law, as well as any other similar laws that both Republican- and Democratic-led states might pass. That's probably unwise at any point in history. At this particular moment, with partisans on both sides so bitterly pitted against each other and with democracy itself seemingly in the balance, such laws would throw kindling on the fire. Instead of trying to resolve our political differences through normal processes and debate — a frustrating slog that often can produce results we hate — Americans would be unleashed to simply sue each other over their political differences, to try to dominate the disagreeable and deplorable into bankruptcy and ruin. Who wants to live in a country like that?

But the proliferation of Texas-style laws wouldn't just pit citizen against citizen: They would probably also serve as a crippling blow to the already shaky legitimacy of the courts. That legitimacy relies, in part, on the courts being seen as fair and reasonably neutral. It's why judges sometimes recuse themselves in cases where they're seen to have a conflict of interest, and why Supreme Court justices have argued so vociferously and unconvincingly in recent months that their job isn't political. (It is, and few people believe otherwise, but for now the fiction must be preserved.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The Texas law mocks the ideal of impartiality by putting a thumb on the scale for pro-life litigants — among other provisions, it allows plaintiffs to recover attorney's fees if they win their lawsuits, but not the abortion providers who would be defending those suits. "These provisions are considerable departures from the norm in Texas courts and in most courts across the Nation," Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in her dissent from the court's Friday ruling. If such procedural trickery leads Americans to believe they can't get a fair deal in the courts, the judicial system will take a nasty hit — and it will be entirely deserved.

Even if the courts somehow manage to survive such a process, it's not clear the country could. America has 50 states, each with a different set of laws that reflect the differing values, priorities, and powers of their voters and leaders: Just ask, say, any Philadelphian who has crossed the Delaware River to New Jersey to avoid dealing with Pennsylvania's weird liquor laws. Those differences can be harmless, if inconvenient. They're mostly accommodated. As Newsom's rhetoric suggests, Texas-style laws could well harden the political divisions between red states and blue states, with radical differences in legal regimes and understandings of civil rights feeding the anger between the two. We've seen how that can work out.

The Texas abortion law is terrible all on its own. Now imagine that kind of law, about all kinds of issues, being passed in states across the country.

I continue to suspect and hope that the law's provisions are so outrageous — for reasons that have nothing to do with abortion — that even a Supreme Court composed mostly of pro-life conservatives will strike it down. The future of abortion rights won't be resolved in Texas. And even if they agree with the ends, justices must understand that the means are too destructive. That would still be the case in the service of an ostensibly good cause like reducing gun violence.

Despite the anger that Newsom and so many pro-choice people feel right now, it's not a model that Democrats should want to replicate — especially as a form of revenge.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military