Turkey is now a huge liability for NATO — and America

It's time for an amicable divorce

When Turkey entered the NATO defense alliance in 1952, it was a major coup for Europe and for America. Turkey had control of the strategically important Bosphorus Strait and the Dardanelles. The NATO alliance could therefore exercise a preemptively tight grip on the Soviet Union's only direct access to Western warm-water ports. Furthermore, Turkey was a secular doorway into the resource-rich Middle East.

But it's now 2015. The Soviet Union has been dead and gone for a quarter of a century. The Middle East is an absolute mess. And 63 years after joining the alliance, Turkey has turned into one of NATO's and America's biggest liabilities in the region. Indeed, there seems to be no hope of re-balancing this alliance to make it a positive one for the West.

The presumption of shared values between Turkey and the West is disappearing. Ataturk's secular state in Turkey is long gone, and Recep Erdogan is slowly putting together a more Islamic state in its place. Press freedoms are being destroyed, clear evidence that Turkey is no longer part of the free world.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Consequently, the terms of the debate between Turkey and Russia have changed since the Cold War, or really, reverted to their more traditional form. Turkey and Russia see each other not just as once-great powers that are often at odds, but as religious-political rivals dating back to the years of Islamic expansion against Christendom. Leaders of both countries use their religious history, perhaps cynically, to justify to their respective publics their foreign policy in the Middle East. NATO was an alliance of the Free World versus Communism. But now, the more resonant axis of conflict between Russia and Turkey is the Ottoman Empire versus Orthodoxy.

Turkey's interests no longer align neatly with the West's. Erdogan's own son is accused of collaborating with ISIS to transport ISIS's oil through Turkey. Turkey has been reckless with Europe's security, by allowing jihadists to travel through it both coming from Europe and returning from the battlefields of Syria. Turkey's major strategic goals in the Syrian civil war do not align with our own, since their first-order concerns are to prevent the Kurds from gaining strength to attack the Turkish state, and to protect Turkmen living in Syria. Removing Bashar al-Assad from power is a lesser goal for them. Defeating ISIS hardly rates at all.

Another huge problem: The NATO alliance creates a moral hazard through its security guarantee to Turkey. Although Turkey has not yet invoked Article 5 — which obliges every member to act in concert in defense of another member — our needy, unstable, and burgeoning dictatorship of an ally acts in increasingly provocative ways, like shooting down a Russian jet, precisely because no one on the Russian or NATO side really wants to put Article 5 to the test. Turkey is now the state in NATO most likely to reveal Article 5 as a bluff, thereby putting the security of nations like Estonia or even Poland into doubt, or precipitating a conflict between Moscow and the West that would be needless, yet difficult to step away from without either side losing face.

Even without Turkey, Russia and the United States already have a highly complicated and difficult relationship when it comes to Syria. Washington and Moscow each claim to have a common foe in ISIS. But each country has made the protection of their different allies their top priority. Russia works primarily to protect Assad. The U.S. looks out for its so-called "moderate rebels." Each nation keeps getting pushed to confront ISIS, but they are simultaneously supporting rivals in anticipation of an internationally brokered ceasefire and peace. Turkey has done nothing but create complications for both sides, in an already confusing situation.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

At the same time, Turkey is taking advantage of our European partners, promising to slow the flow of migrants and refugees to Europe only if Europe coughs up a tremendous amount of cash. The Turks also want to be able to grant their millions of citizens EU visas. Essentially, Turkey's proposition is that they'll stop the flow of Syrians, if only Europe opens the door wide to Turks.

Like so many other states in the region, Turkey's alliance with the United States is now high-risk and low-upside. Sixty-three years is a pretty damn good run in the history of diplomacy. But now is the time to ease our way to an amicable divorce.

Michael Brendan Dougherty is senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is the founder and editor of The Slurve, a newsletter about baseball. His work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, ESPN Magazine, Slate and The American Conservative.

-

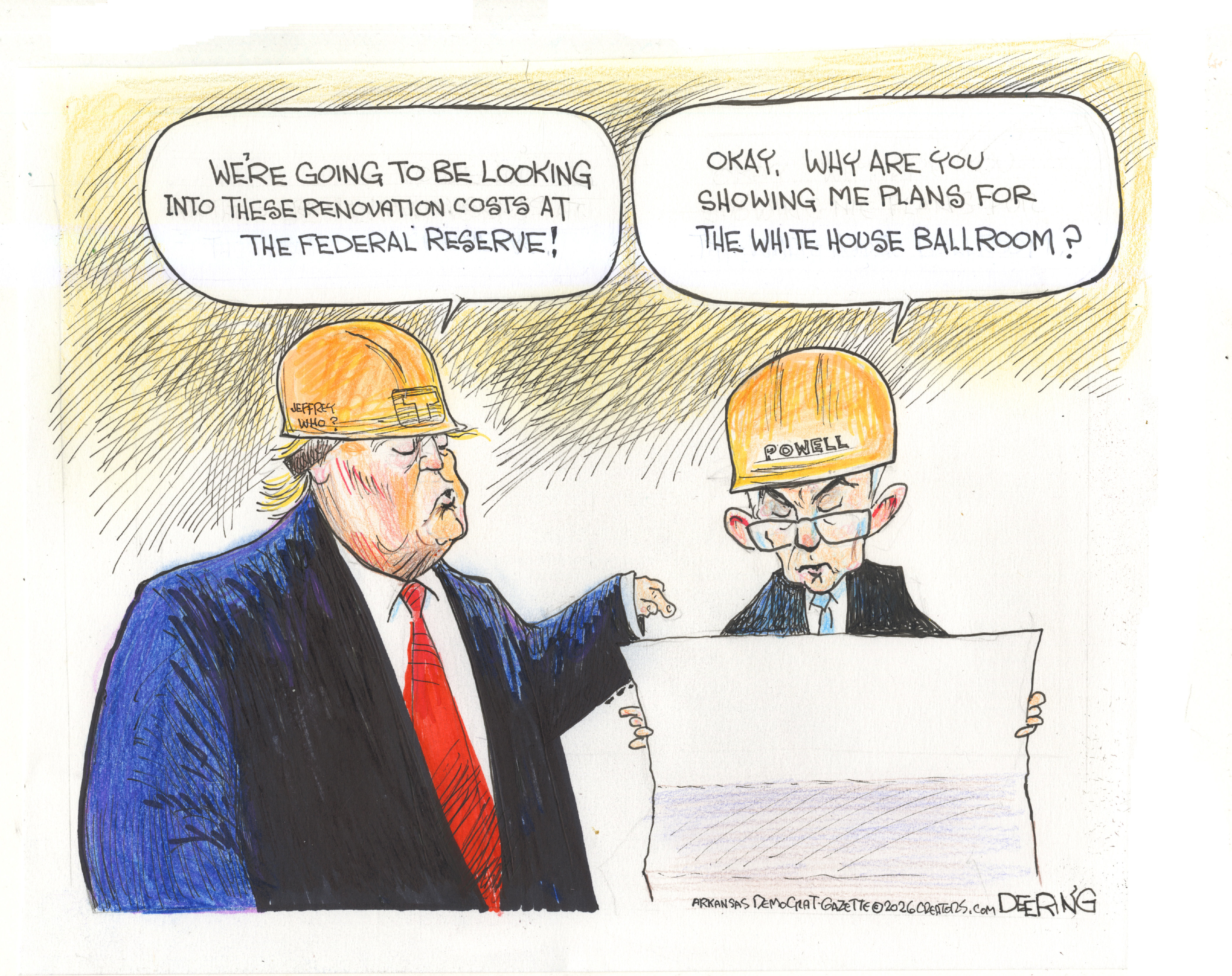

Political cartoons for January 17

Political cartoons for January 17Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include hard hats, compliance, and more

-

Ultimate pasta alla Norma

Ultimate pasta alla NormaThe Week Recommends White miso and eggplant enrich the flavour of this classic pasta dish

-

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the US

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the USIn the Spotlight Federal response to Renee Good’s shooting suggest priority is ‘vilifying Trump’s perceived enemies rather than informing the public’

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military

-

How Bulgaria’s government fell amid mass protests

How Bulgaria’s government fell amid mass protestsThe Explainer The country’s prime minister resigned as part of the fallout

-

Femicide: Italy’s newest crime

Femicide: Italy’s newest crimeThe Explainer Landmark law to criminalise murder of a woman as an ‘act of hatred’ or ‘subjugation’ but critics say Italy is still deeply patriarchal

-

Brazil’s Bolsonaro behind bars after appeals run out

Brazil’s Bolsonaro behind bars after appeals run outSpeed Read He will serve 27 years in prison

-

Americans traveling abroad face renewed criticism in the Trump era

Americans traveling abroad face renewed criticism in the Trump eraThe Explainer Some of Trump’s behavior has Americans being questioned

-

Nigeria confused by Trump invasion threat

Nigeria confused by Trump invasion threatSpeed Read Trump has claimed the country is persecuting Christians