The fall and rise of full employment

How Democrats fell back in love with a spurned priority

Buried on page seven of the Democratic Party's 2016 platform is a seemingly innocuous phrase: "[W]e are committed to doing everything we can to build a full-employment economy." If you haven't been following economic policy debates closely for the past few years, you probably wouldn't recognize that this is a big deal.

A favorite term of liberal wonks, "full employment" refers to the moment when demand for labor pulls roughly even with supply. At that point, there's such a glut of job openings that employers start fighting over workers instead of the other way around. This competition spurs working conditions to improve, schedules to lighten, benefits to grow, and wages to rise. The American worker doesn't just get a job — his life improves measurably.

Three decades ago, full employment was an explicit priority for Democrats, appearing in some form in every party platform from 1944 to 1988. But in 1992, it abruptly vanished. Now, 24 years later, a polyglot movement of activist organizations, think tanks, economists, and politicians have finally brought it back.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

One of the key figures in this fight was Rep. John Conyers (D-Mich.), who told The Week he was particularly drawn to the racial justice benefits of full employment. Historically, the gap between African-American and white unemployment shrinks during times of full employment — a tendency that was borne out in 2000. Then, during a brief burst of full employment, the black unemployment rate fell to its "lowest documented rate in U.S. history, and the smallest gap between black and white unemployment rates the country had ever seen during an economic expansion," he said.

So, in 2014 — 22 years after full employment first disappeared from the Democratic platform — Conyers helped create the Full Employment Caucus in the House of Representatives. The caucus now boasts 32 members, many of whom worked on the committees that helped draft this year's Democratic platform. Some also reached out to Hillary Clinton's team. Meanwhile, the Fed Up campaign and the Economic Policy Institute both helped organize pressure and gather signatures.

Because the Federal Reserve plays a key role in full employment — since the Fed must choose between fighting inflation and allowing job creation when it sets interest rates — the associated movements were closely linked. Conyers and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) wrote a letter insisting on more racial and gender diversity on the Fed's decision-making board, and for members of the financial industry to be kept off. It was signed by 125 members of Congress and endorsed by Clinton. "That helped to educate Democrats and party officials about [full employment] and demonstrated a broad consensus," Conyers said.

The Fed reform language made it onto the initial draft of the platform, which came out July 1. The ongoing pressure got the commitment to full employment onto the final version.

So that's the fairly straightforward story of full employment's restoration. The story of why it fell is more complicated and intimately tied to how the Democratic Party understands itself.

"Full employment used to be a central goal for the Democratic Party and, truthfully, for the American political system as a whole," Ady Barkan, who directed the Fed Up campaign, told The Week. "The party's base is rejecting the centrist, pro-corporate agenda that dominated the party in the 1990s."

But for the architects of the 1992 Democratic platform — people like Al From, who founded the centrist Democratic Leadership Council (DLC), and headed it up at the time — it was a question of dealing with a different era. "We had just suffered the three worst elections of any party consecutively in American history," From told The Week. "After the 1988 election, people were saying Democrats would never win the presidency again."

Americans were also experiencing a labor market different than today's. The percentage of Americans in the labor force was much higher in 1992 than it is now. The unemployment rate — the percentage of that labor force without jobs — did peak at an ugly 7.8 percent, but it never hit the 10 percent that followed the Great Recession.

Then-Arkansas governor and presidential nominee Bill Clinton, From himself, and the other members of the DLC concluded the primary need at the time was faster economic growth. "That was the buzzword, as opposed to full employment," explained former New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson (D), who helped draft the 1992 platform. "It wasn't a rejection of full employment or income inequality issues, but it was moving the party to the economic center more."

This was hardly crazy — economics has long recognized a relationship between the pace of GDP growth and the overall level of employment in the economy. So the strategy was three-part: expand trade; invest in technology, training, and education; and finally raise taxes and cut spending to shrink the budget deficit. The theory was cutting the deficit would indirectly create jobs by bringing down interest rates, which would encourage more private sector investment and consumption. It was the "supply side" route to full employment.

This was a departure from the "demand side" route associated with the labor politics and economic populism of Franklin Roosevelt. In that approach, the government intentionally uses temporary deficits to finance infrastructure and other public investments, drive up aggregate demand, and create jobs directly. Then the Fed steps in to keep interest rates down.

For Dean Baker, the director of the Center for Economic Policy Research, and co-writer of a book on full employment, the disappearance of full employment signaled a policy switch from the demand side to the supply side route. "I took the removal of that to be saying, well, the government doesn't have that direct responsibility," Baker told The Week. "Clinton wanted to make a statement. He doesn't believe that outdated stuff."

Ostensibly, though, the supply side was vindicated: By everyone's metrics, the economy achieved a burst of full employment in the late 1990s. By 2000, the unemployment rate had dropped to a startling 4 percent, a level unheard of since the 1960s. The period is remembered as a kind of mini economic golden age in American politics.

There were complications, however. The consumption and investment that fueled the late '90s boom was deeply bound up with the dot-com bubble in the stock market. Later, the recovery in the 2000s was driven by the housing bubble. Both, needless to say, ended quite badly. And those busts implicated other policy decisions of the era: The Fed failed to warn investors off the bubbles, bipartisan financial deregulation allowed Wall Street to gorge on toxic assets, and the expansion of the trade deficit at the same time the government was tightening its belt forced the private sector to rely on economic bubbles to compensate. So while the achievement of full employment in the '90s was real, the composition of forces that produced it left something to be desired.

Ultimately, the one thing everyone definitely agreed on was that the economic world of 2016 is vastly different from that of 1992.

Almost eight years after the Great Recession, the unemployment rate may be at 4.9 percent, but the labor force has collapsed. The key signs of full employment — robust wage growth, rising inflation, an even ratio of jobs to job seekers — haven't shown up, despite interest rates reaching historic lows. So the supply side mechanism, where low interest rates encourage the private economy to heal itself, appears entirely broken. "Certainly no one [in 1992] was talking about a situation where you have very low interest rates, even negative interest rates, in countries across the globe, and yet still aren't achieving full employment," Jared Bernstein, a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and former chief economist to Vice President Joe Biden said. "That wasn't something we knew about."

So today, advocates of full employment focus on a few key points. First is the Federal Reserve reforms. But they also want to get serious about the demand side route again. Conyers has proposed a bill to both train workers for new jobs and have the government create jobs directly. And Bernie Sanders wants to drop $1 trillion in new spending to update the country's infrastructure. Even Obama pitched a $450 billion bill in 2012, to modernize infrastructure and boost public and private hiring. But it died in the legislature.

"Congress should stop blocking needed job creation measures," Conyers said. "In the richest country on Earth, I continue to share the view of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. that we can afford to provide employment to every American who wants to work."

Maybe the most dramatic evidence of the shift is economist Larry Summers. Back in the 1990s, he was a key official in Bill Clinton's White House, and helped engineer the centrist reinvention of Democratic economic policy. All of which earned him the enduring animosity of the Democratic Party's left wing.

Yet today, no one is insisting on demand side measures louder than he.

"Circumstances change," From observed. "And you really have to change with them."

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Meet Youngmi Mayer, the renegade comedian whose frank new memoir is a blitzkrieg to the genre

Meet Youngmi Mayer, the renegade comedian whose frank new memoir is a blitzkrieg to the genreThe Week Recommends 'I'm Laughing Because I'm Crying' details a biracial life on the margins, with humor as salving grace

By Scott Hocker, The Week US Published

-

Will Trump fire Fed chair Jerome Powell?

Will Trump fire Fed chair Jerome Powell?Today's Big Question An 'unprecedented legal battle' could decide the economy's future

By Joel Mathis, The Week US Published

-

Sri Lanka's new Marxist leader wins huge majority

Sri Lanka's new Marxist leader wins huge majoritySpeed Read The left-leaning coalition of newly elected Sri Lankan President Anura Kumara Dissanayake won 159 of the legislature's 225 seats

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

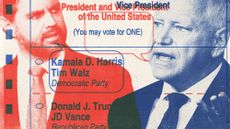

US election: who the billionaires are backing

US election: who the billionaires are backingThe Explainer More have endorsed Kamala Harris than Donald Trump, but among the 'ultra-rich' the split is more even

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?

By The Week UK Published

-

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?Today's Big Question 'Diametrically opposed' candidates showed 'a lot of commonality' on some issues, but offered competing visions for America's future and democracy

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

1 of 6 'Trump Train' drivers liable in Biden bus blockade

1 of 6 'Trump Train' drivers liable in Biden bus blockadeSpeed Read Only one of the accused was found liable in the case concerning the deliberate slowing of a 2020 Biden campaign bus

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

How could J.D. Vance impact the special relationship?

How could J.D. Vance impact the special relationship?Today's Big Question Trump's hawkish pick for VP said UK is the first 'truly Islamist country' with a nuclear weapon

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Biden, Trump urge calm after assassination attempt

Biden, Trump urge calm after assassination attemptSpeed Reads A 20-year-old gunman grazed Trump's ear and fatally shot a rally attendee on Saturday

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published