European Parliament elections: three challenges facing the EU

The Continent appears more divided than ever as voters go to the polls

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

More than 400 million voters are exercising their democratic rights together this week in the world’s second-largest elections, yet Europe is a continent divided.

Although surveys suggest approval rates for EU membership is currently at a record high across the bloc, many commentators fear that support is set to crumble.

In 11 of 14 countries recently surveyed by YouGov and the European Council on Foreign Relations, the majority of respondents reported anticipating a possible EU collapse within the next two decades.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

“For a project that once seemed like a beacon of hope for values-based global cooperation, this is a devastating reversal,” says Spain’s former minister of foreign affairs, Ana Palacio, in an article for global affairs commentary site Project Syndicate.

So what are the challenges facing the EU?

C'est l'économie, stupide!

A decade after the financial crisis ripped through the Continent’s economy, throwing its political and social model into disarray, average annual growth remains at just 1.5%. And “there are strong signals that worse is to come: debt levels are rising fast and the European Central Bank has relaunched stimulus measures to stave off recession”, says Palacio on Project Syndicate.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Indeed, “Europe has plenty of world-class companies but unlike the US, none of them were set up in the past 25 years,” says The Guardian’s Larry Elliott. “There is no European Google, Facebook or Amazon, and in the emerging technologies of the fourth Industrial Revolution, such as artificial intelligence, Europe is nowhere.”

French President Emmanuel Macron is convinced that the answer to Europe’s economic problems is closer integration, with the EU appointing a finance minister in charge of tax and spending policy for the entire eurozone.

Macron also “envisions a two-speed Europe which would allow countries that want to work towards further integration to go forward with such measures while others can choose to maintain the status quo”, reports Deutsche Welle.

But to do that he needs the support of Germany, and Berlin “has been notably reluctant to support Macron’s proposal of pooling financial resources, in what many in Germany’s parliament believe would create a ‘transfer union’ that would likely see Germany provide more financial resources than it would receive from a collective fund”, the newspaper adds.

The German authorities are not alone in holding such fears. In March, Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babis described the two-speed system proposal as “totally divorced from reality”, says Reuters.

“I have noticed that when France says ‘more of Europe’, she in fact means more of France. But that is not the way. We are all equals in Europe,” Babis was quoted as saying.

All the same, Macron’s plan “has a logic to it”, says The Guardian’s Elliott. “The eurozone is a half-completed project, lacking the political structure that would give it a chance of working...What’s more, if Europe continues to underperform economically, the alternative to closer integration is disintegration,” he concludes.

Popular populists

Another challenge facing the EU is the rise of those wishing to bring about its demise from within. Eurosceptic parties have always had a presence in the European Parliament, but traditionally they’ve struggled to wield substantial influence.

As Vox’s Jen Kirby notes, their “staunchly nationalistic views aren’t exactly a successful formula for cooperation in the pan-European political body”.

But Italy’s Matteo Salvini, France’s Marine Le Pen and the Netherlands’ Thierry Baudet are trying a new tactic: attempting to build a cross-continent alliance of anti-EU parties. Other far-right parties have joined the cause, including Germany’s Alternative for Deutschland (AfD) and Austria’s Freedom Party, and “they’re betting that by working together, they can weaken - and remake - the EU from within”, says Kirby.

Macron has pitted himself as the leader of anti-populist forces in opposition to the group, while European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker has warned voters against using the elections as a protest platform.

But the extremist parties are still expected to do well, so the European Parliament that sits in July is expected to be more divided, “raising the risk of paralysis as the old pro-European parliamentary coalition falls away”, says The Guardian.

Far-right Euroskeptics are trying to appeal to the dissatisfied with the status quo. “They’re positioning themselves as the parties of change but within still the bigger European idea,” Susi Dennison, a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, told Vox.

So what they represent is no longer opposition to the existence of the European Union - it’s opposition to the European Union “as it exists now, at least according to the far-right skeptics: too powerful, too progressive, too multicultural”, says Kirby.

East meets West

An East-West divide has also emerged among the member states. Hungary’s nationalist prime minister, Viktor Orban, is pushing his vision of illiberal democracy and “has become a trendsetter for the centre–right throughout much of the Continent”, says The Spectator’s John O’Sullivan.

Over the past five years, “a crack has grown into a chasm, as Hungary and Poland have suppressed independent media, attacked NGOs, and undermined judicial independence”, adds Palacio on Project Syndicate. This has driven EU leaders to take the unprecedented step of triggering sanctions procedures against their governments for eroding democracy and failing to adhere to fundamental EU norms.

Although majorities in the European Parliament backed the sanctions, the support has been less than enthusiastic, “leaving the EU institution-driven process toothless”, according to Palacio.

In a move seen as a direct riposte to the bloc’s direction of change, the Polish government put forward a proposal this week to create a “red card” system allowing national parliaments to veto EU laws.

Alongside Poland and Hungary, Romania is also in the sights of the European Commission for failure to respect the rule of law. Meanwhile, Salvini, Le Pen and pals chose Slovakia as the site of a meeting earlier this month of the most prominent European far-right parties.

Fuelling fears of a lack of buy-in to the EU among those in the East is the fact that ten of the 12 countries with the lowest turnouts in the 2014 elections were from the former communist bloc. Voting in these nations is “a little less sacred” than in other European countries, French university professor Olivier Rozenberg told French news agency AFP.

“For us (Western countries), voting is synonymous with democracy, while this link is less clear in Eastern countries where there are still memories of non-pluralist elections,” he said.

-

Political cartoons for February 16

Political cartoons for February 16Cartoons Monday’s political cartoons include President's Day, a valentine from the Epstein files, and more

-

Regent Hong Kong: a tranquil haven with a prime waterfront spot

Regent Hong Kong: a tranquil haven with a prime waterfront spotThe Week Recommends The trendy hotel recently underwent an extensive two-year revamp

-

The problem with diagnosing profound autism

The problem with diagnosing profound autismThe Explainer Experts are reconsidering the idea of autism as a spectrum, which could impact diagnoses and policy making for the condition

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

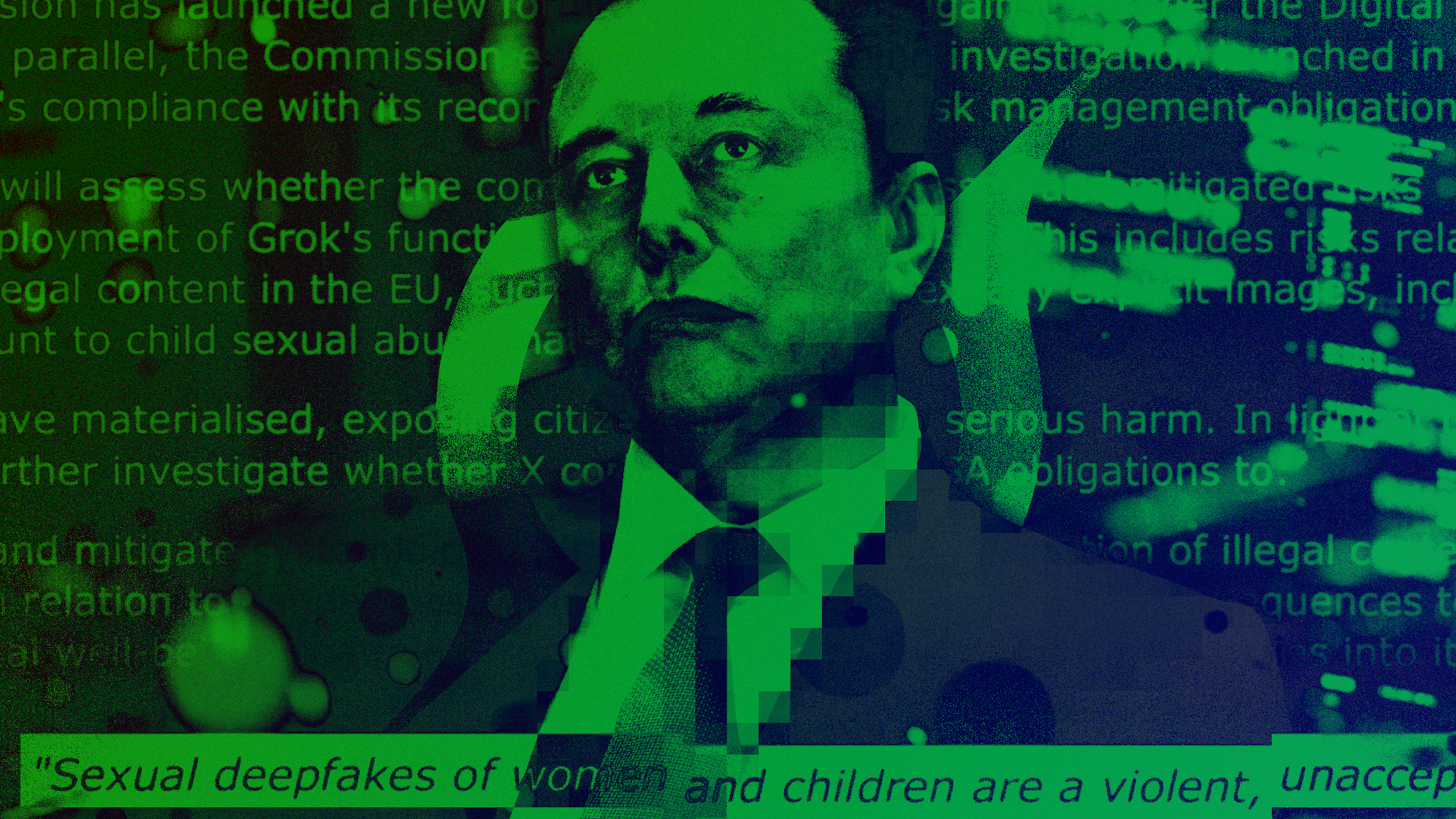

Grok in the crosshairs as EU launches deepfake porn probe

Grok in the crosshairs as EU launches deepfake porn probeIN THE SPOTLIGHT The European Union has officially begun investigating Elon Musk’s proprietary AI, as regulators zero in on Grok’s porn problem and its impact continent-wide

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Europe moves troops to Greenland as Trump fixates

Europe moves troops to Greenland as Trump fixatesSpeed Read Foreign ministers of Greenland and Denmark met at the White House yesterday

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult