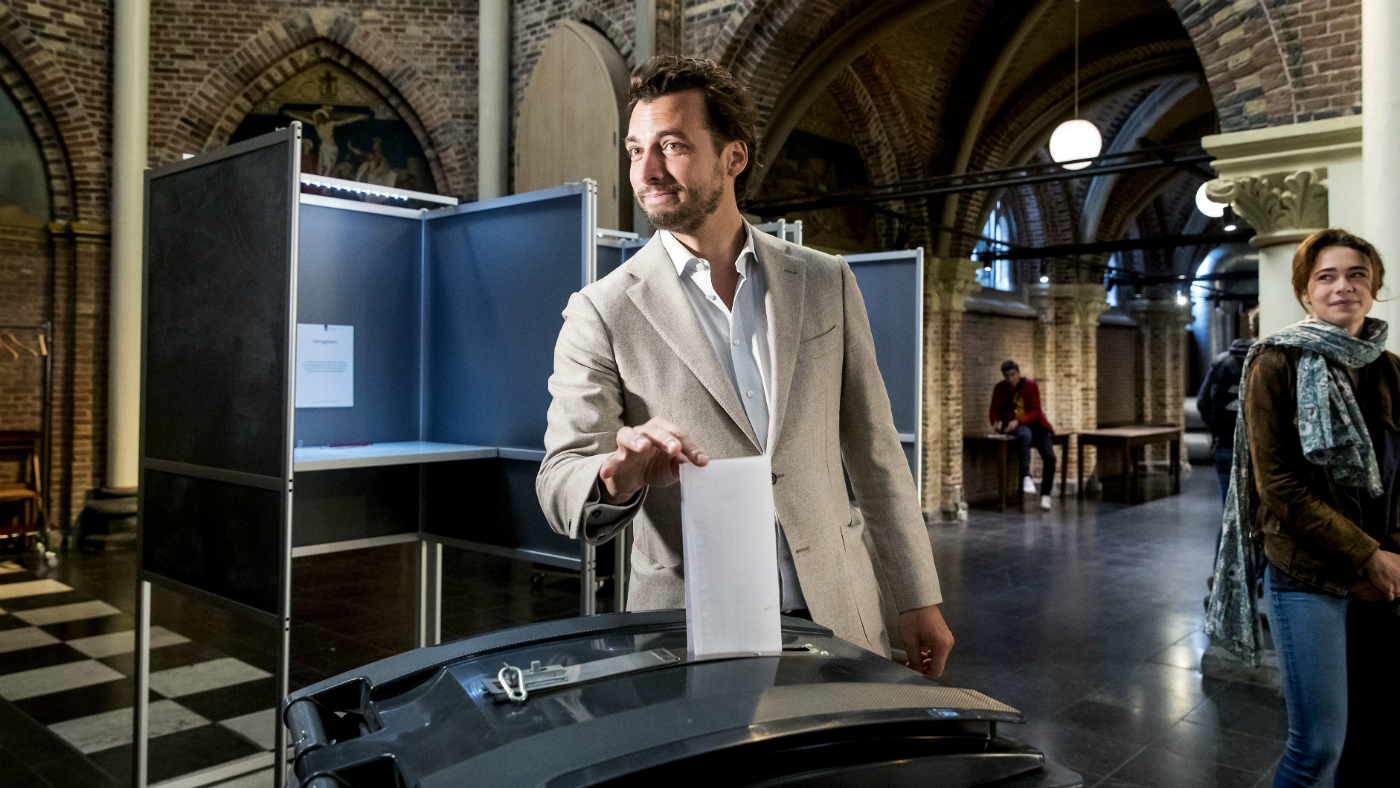

Thierry Baudet: the Dutch nationalist out to take Europe by storm

The controversial candidate’s Forum for Democracy (FvD) is on course to be largest Dutch party at this week’s European elections

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As citizens across Europe head to the polls today, pundits are predicting a surge in support for the Continent’s myriad populist parties as voters turn their backs on the Establishment.

But few populist politicians have seen their support base swell so much as that of Thierry Baudet, the founder and leader of the Forum for Democracy (FvD), a controversial far-right party in the Netherlands that was formed just three years ago.

Described by The Times as a “populist upstart”, the 36-year-old’s outspoken views have seen the FvD poll neck-and-neck with Dutch President Mark Rutte’s ruling liberal People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD).

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Where many far-right populists present themselves as representatives “of the people”, championing the working class and decrying elitism, Baudet’s approach is rather difference.

The Guardian describes him as a “philosopher-dandy with a penchant for playing piano in his office, posing nude on social media and quoting Latin in parliament”. Left-leaning US news site Jacobin says the FvD is “the most self-consciously elitist party in the Dutch political landscape”.

“The FvD candidate list is made up of lawyers, surgeons, corporate managers, businessmen, retired military officers, and most of all the FvD’s programmatic statements promise class war from above on all fronts,” the site adds.

Yet despite his elitist image, Baudet’s meteoric rise comes as no surprise to many commentators. The New Statesman notes that the Dutch have “experienced the same universal factors that tend to foster populism” across the Western world, including “deindustrialisation, a neoliberal consensus, social fragmentation and migration”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And by using often heavily coded rhetoric, the FvD leader has maneuvered his way into mainstream political discourse, offering “a fundamentally racist, authoritarian and nativist project in centre-right – or more precisely, middle-class – clothing”, according to the news site.

So just how did Baudet rise to political prominence, and how big a role will he play in the predicted populist earthquake at the EU elections?

Who is Thierry Baudet?

Born in the Dutch town of Heemstede in 1983, Baudet studied law at university before going to work as a columnist for NRC Handelsblad, a liberal newspaper based in Amsterdam, in 2011.

However, after leaving the paper the following year, his politics quickly veered to the extreme nationalist right. Baudet subsequently published multiple books laying out his strongly anti-immigration and Eurosceptic views, with titles including The Attack on the Nation State and Oikophobia: the fear of home.

According to The Guardian’s Joost de Vries, over the years Baudet has spoken out in favour of Donald Trump and Viktor Orban’s strongly anti-immigration policies, “made friends in France with Le Pen (father and daughter), and sided with Vladimir Putin over MH17”, the Malaysia Airlines flight carrying 193 Dutch nationals that was shot down over Ukraine in 2014.

The nationalist leader has also been “flirting with Nexit” for a long time, “constantly calling Brussels the root of all evil”, de Vries adds.

In 2015, Baudet founded the FvD, which was initially conceived as a Eurosceptic think-tank to campaign in the Dutch Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement referendum the following year.

In September 2016, Baudet converted the FvD to become a political party, and quickly gained support from the Dutch upper and middle classes.

Political career

The anti-Islam Party for Freedom (PVV) and its leader Geert Wilders have dominated far-right populist discourse in the Netherlands during much of this decade, and conform to “stereotypes of the far-right, with controversial rallies dominated by thuggish chants of ‘less Moroccans’”, The Times reports.

So Europe was “stunned” when Baudet’s FvD became the largest party in the Dutch senate at the provincial elections in March, says The Japan Times.

The New Statesman argues that Baudet and the FvD have “eclipsed” Wilders and the PVV as bastions of the far-right in the Netherlands, but Jacobin suggests that voters migrating from the PVV to the FvD are not making a like-for-like switch.

Wilders, who initially sat on the right wing of Rutte’s secular neoliberal VVD party, left in order to launch the PVV and subsequently “postured as a defender of the welfare state, claiming the real threat to it was immigration and that immigrants’ access to social security needed to be restricted further”, says Jacobin.

“Conversely, the FvD election manifesto calls for destroying laws that protect workers against dismissal and in case of illness, for selling off social housing, and abolishing inheritance taxes as well as subsidies for tenancy and healthcare costs,” the site adds.

During a 20-minute victory speech - some of which was in Latin - following the March election, Baudet said that voters had punished the Dutch establishment for their “arrogance and stupidity”, adding that the FvD and its members “have been called to the front because our country needs us”.

He also spoke of preserving the “boreal world”, an obscure term meaning Northern European or white.

Why are people flocking to the FvD?

Latest polls suggest Baude’s party and Rutte’s ruling VVD are level pegging, with both claiming around 15% of the vote share. The Dutch Labour party (PvdA), GreenLeft and Christian Democratic Appeal follow close behind, on around 13% each.

The Times reports that there is a “real prospect” of Baudet’s party now edging ahead to beat Rutte’s, despite the VVD “having dominated Dutch politics for 25 years”.

The reasons for this swing are a matter of debate.

“Voters have become more extreme,” Amy Verdun, European politics professor at Leiden University, told the South China Morning Post this week. “The populists made things simple. You may not agree with them, but they simplify things for the ordinary citizen.”

The Guardian’s de Vries suggests that this surge in right-wing support may also be a result of the sidelining of Wilders, whom many voters believed to be “too crude or uncivilised” to back. “Now feel they have someone they can vote for without feeling crude themselves,” he adds.

That view is echoed by Claes de Vreese, politics professor at the University of Amsterdam. “He does attract a certain audience of voters who may be disgruntled by the fact that Wilders’ style is very confrontational and not particularly intellectual,” de Vreese says.

What will an FvD surge mean?

To some, the rise of the FvD is far more worrying than the previous surges by the PVV.

According to Politico, opponents of Baudet see him as a “pseudo-intellectual whose sophisticated air masks extreme-right views, economically disastrous ideas, misogyny and policies that contravene international law”.

Although the PVV has called for the banning of the Koran, the party also claims to be defending Dutch liberal values, whereas Baudet seems to “flirt with ideas that are openly fascist”, the news site continues. The FvD boss frequently mingles with controversial hate figures, and reportedly had an extended meeting with US white supremacist Jared Taylor late last year.

GreenLeft leader Jesse Klaver argues that Baudet fosters a “sad old-fashioned view of men and women for a young guy”, and that claims that his “flirting with right-wing extremism is a coincidence is naive”.

“Anyone who thinks that Baudet stands up for women's rights is wrong,” Klaver says. “Anyone who thinks that Baudet serves the interests of the Dutch will be disappointed.”

Like the PVV before them, however, not everyone believes that the FvD are here to stay. University professor Verdun believes that most voters will ultimately back centrist parties, not least due to the “repeated failure of squabbling populist and far-right parties to unite within the European Parliament”.

“The populists’ problem is that they can never agree on anything,” she said. “If they don’t capitalise on their result, the populists will never get much further.”