Is the EU democratic?

As London and Brussels struggle to agree a Brexit deal, The Week takes a look at the structure of the bloc

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The run-up to the 2016 Brexit referendum saw the launch of a campaign that many commentators claim used immigration scare stories and xenophobia to persuade voters to quit the European Union.

Vote Leave allegedly “relied on racism” to appeal to the British public’s inherent prejudices, as Martin Shaw wrote in The Guardian last year. Regardless of such accusations, the anti-EU campaign secured a 52% to 48% victory in the Brexit vote, under the snappy slogan “Take Back Control”.

This slogan appears to have struck a chord with the many Leave voters who believe the EU represents a democratic vacuum. Leading Brexiteer Nigel Farage repeatedly refers to EU politicians as “unelected bureaucrats”, while the Vote Leave campaign website describes the institution as “undemocratic”.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

With a no-deal Brexit now looming as UK-EU trade tensions grow, The Week takes a look at the inner workings of the bloc.

How is the EU structured?

The EU is comprised of a number of institutions that work together but have very different functions.

First is the European Council. “The EU’s broad priorities are set by the European Council, which brings together national and EU-level leaders,” says the official EU website. Or to put it another way, the council is a collection of leaders who were democratically elected within their own borders.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The European Parliament, meanwhile, is the only directly elected EU body, with representatives, or MEPs, apportioned by each member state’s population. The Parliament is unusual in that it cannot propose legislation, but EU laws cannot pass without its direct approval. The current president of the Parliament is Italian politician David Sassoli, who was chosen by MEPs.

The most controversial institution of the EU is the European Commission. This is the executive branch, meaning it submits proposals for new legislation to the Parliament and the Council, implements EU policy and administers the budget. Most crucially, the commissioners are not elected but are instead nominated by member countries, each of which gets one representative.

During his final appearance in the European Parliament in Brussels in January, Nigel Farage told his fellow MEPs that “if we want trade, friendship, cooperation, reciprocity, we don’t need a European Commission”.

He added: “It isn’t just undemocratic, it’s anti-democratic and it puts in that front row, it gives people power without accountability – people who cannot be held to account by the electorate.”

The EU defends this set-up on its website by pointing out that all EU laws handed down by the Commission can “only be approved by democratically elected politicians” in the Parliament, which “also endorses new Commissions, holds the Commission to account and can even force the Commission to resign in a so called ‘motion of censure’”.

So is the EU democratic?

As the UK in a Changing Europe think tank notes, “‘democracy’ means different things to different people” - so there are no easy answers to this question.

“To take the most obvious example, when we talk about democracies, we often mean representative democracies, where we elect people to represent our views and make decisions on our behalf,” says the independent research organisation.

“That’s very different from a direct democratic approach where, like in the EU referendum, many or all decisions are taken by the population at large.”

And although the EU is an “international organisation, like the United Nations or Nato, founded on treaties between its member countries”, the bloc “far surpasses other international organisations in its democratic control” and “reaches into far more areas of public policy than its counterparts elsewhere”.

Given the conflicting interpretations of what democracy means and how far the EU’s powers should extend, the think-tank concludes that “there are still questions about the right balance to strike”.

To some commentators, the question of EU democracy hinges more on accountability than representation. Writing for the London School of Economics (LSE) blog, historian Pippa Catterall suggests that the idea of the EU being undemocratic may stem from its functional differences to national governments.

Large swathes of the EU are effectively appointed by a voting populace - a decidedly democratic facet of the institution.

But “because it remains fundamentally an international organisation, it does not have a ‘government’ which can be voted out by the disgruntled,” says Catterall, a professor of history and policy at the University of Westminster. “Its parliament makes laws and holds confirmation hearings on appointees, but those appointees are placed there by horse-trading between the member states, rather than directly.

“In that sense, the EU’s organisation falls some way between that of an international organisation (which few people expect to be democratic), and that of a state. However, the more the EU seems to resemble a state rather than an international organisation, the more it has become judged by the normative expectations of how democratic the former rather than the latter are.”

Transparency is another key issue in perceptions about whether the EU is democratic.

In an article on The Conversation, Alan Butt Philip, a former Reader in European integration at the University of Bath, writes: “The elected governments of the member states are not keen to grant access to debates in the Council, which are held behind closed doors – and where most important decisions are made. These meetings can’t be watched online and minutes are not made public. Not even representatives of the European Parliament can attend.

“This is difficult to square with the claim of being democratic.”

So is the EU undemocratic? It depends on both which lens we view the question through, and the standard to which we hold the EU.

FullFact concludes that “compared to a country, the EU has democratic shortcomings”, but adds that the most “obvious remedies would imply a considerable strengthening of EU powers, making it look even more like a state”.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

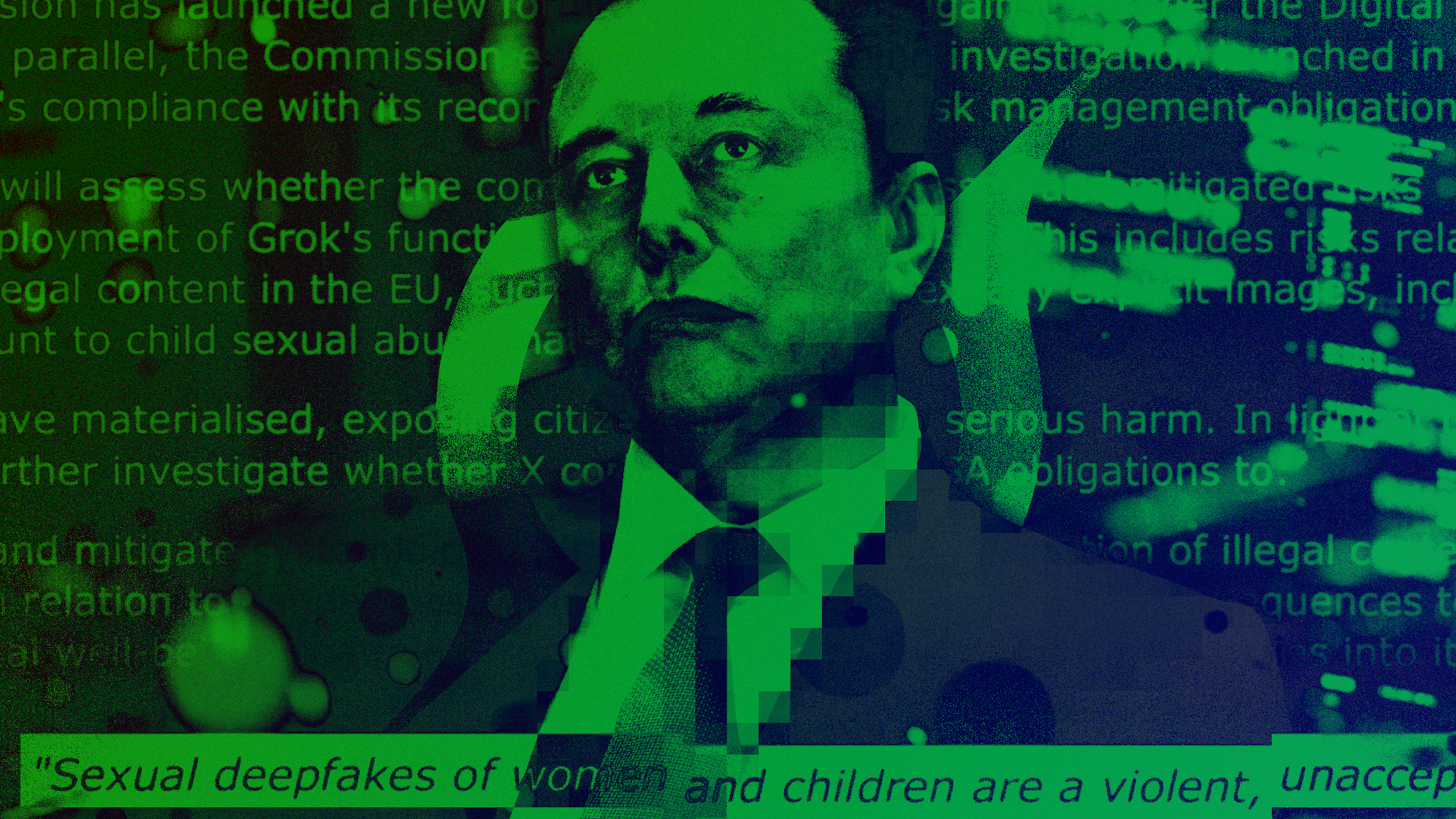

Grok in the crosshairs as EU launches deepfake porn probe

Grok in the crosshairs as EU launches deepfake porn probeIN THE SPOTLIGHT The European Union has officially begun investigating Elon Musk’s proprietary AI, as regulators zero in on Grok’s porn problem and its impact continent-wide

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Europe moves troops to Greenland as Trump fixates

Europe moves troops to Greenland as Trump fixatesSpeed Read Foreign ministers of Greenland and Denmark met at the White House yesterday

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult