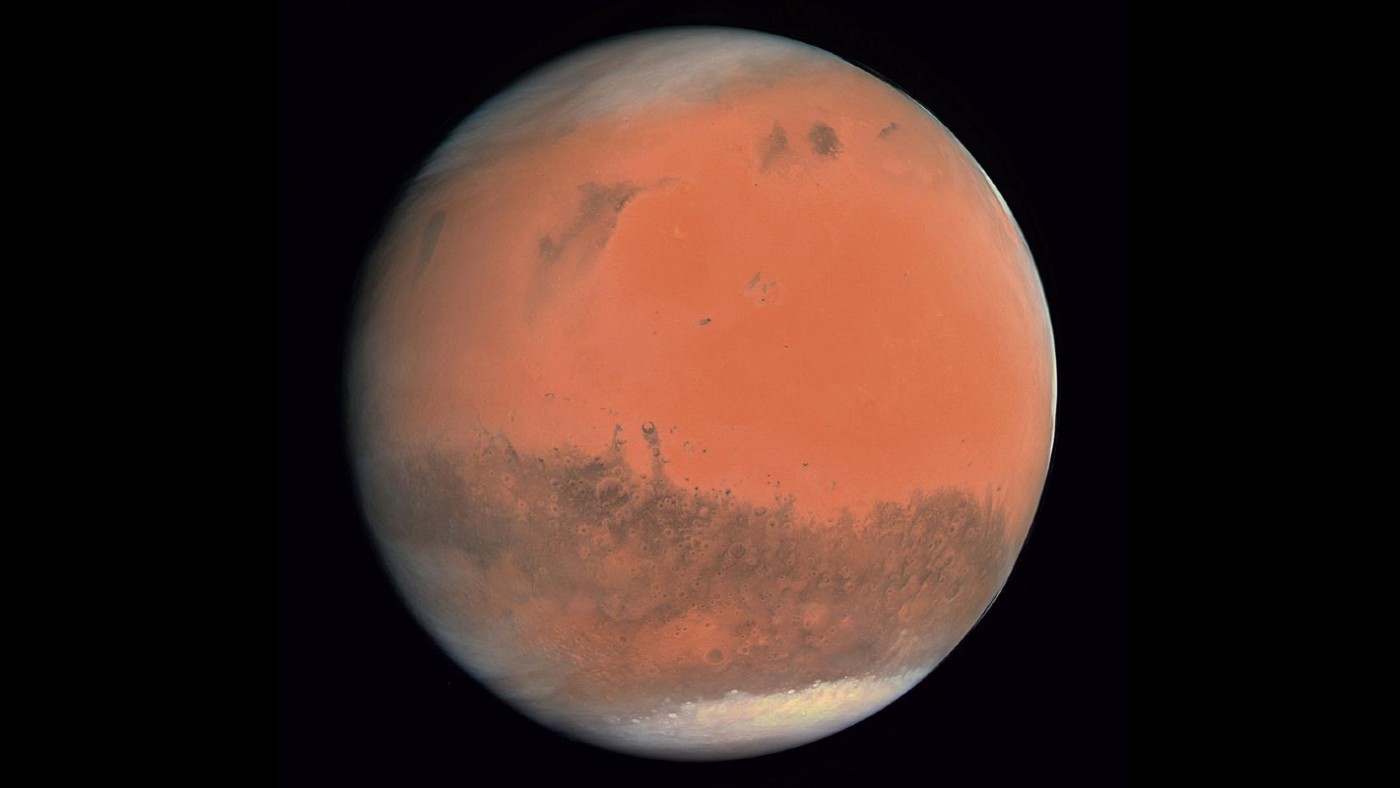

Exploring the red planet

A new wave of missions aim to unlock the secrets of Mars

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Why do we explore Mars at all?

To search for life. Mars has long been considered the most hospitable place in the solar system beyond Earth, for both alien life and future human habitation. The second closest planet to ours after Venus, it is visible to the naked eye; its red-tinged terrain has been more closely observed via telescope since Galileo’s time. Over the centuries we’ve learnt that it is similar to Earth in many ways: it has clouds, winds, a roughly 24-hour day, seasons, polar ice caps, volcanoes and canyons. In the 19th century, scientists thought there were oceans and vegetation on its surface, even canals. We know now that it is a frozen desert (temperatures range from -140ºC to +30ºC in the equatorial summer), but in the past it seems to have had a warmer, denser atmosphere, with rainstorms, rivers and lakes. Even today it has all the ingredients necessary for life: water, organic carbon and energy.

When did exploration first begin?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The first successful fly-by mission to Mars, the Mariner 4 probe, was made by Nasa in 1965. For centuries, humans had speculated about life on Mars, but the 21 grainy black and white images beamed back to Earth by Mariner 4 – the first photos humans had ever seen of another planet – showed a cratered, lifeless surface, much like the Moon’s. These pictures, along with measurements of Mars’s thin atmosphere – about 100 times thinner than Earth’s, therefore exposing it to the harshness of space – prompted The New York Times to declare it a “dead planet”. Since then, humans have launched some 50 missions, about half of which failed. There were many disappointments. The first human-built object to reach Mars, the Soviet lander Mars 2 in 1971, failed seconds after landing. In 1976, Nasa’s Viking 1 and Viking 2 landed safely, but found no evidence of biological activity.

So why did they carry on?

Later missions were more promising. Nasa’s rovers, starting with Spirit and Opportunity in 2004, have found evidence of ancient oceans and streams, and of ice beneath the surface. In 2018, the Curiosity rover found organic deposits trapped in mudstone formed 3.5 billion years ago. It gathered samples, heated them and analysed the results, proving they contained organic molecules: something like kerogen, the fossilised solid organic matter found in sedimentary rocks on Earth. This suggests that life could have existed in Mars’s ancient history, but it doesn’t prove it: the molecules could have been formed by geological activity or meteorites. In 2004, the European Space Agency’s Mars Express orbiter found the first evidence of methane on Mars – also perhaps a sign of former life.

What is happening now?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Last month, Nasa’s Perseverance became the fifth rover to land on Mars (all four of the others were built by Nasa; it and Curiosity remain operational). But two other high-profile missions have also reached Mars in recent weeks: China’s first independent mission, the Tianwen-1 (a spacecraft which is also due to land a rover this year); and the Emirates Mars Mission (the first Arab interplanetary space mission). Each of them set off in July last year, when Mars and Earth were aligned favourably.

What will Perseverance do?

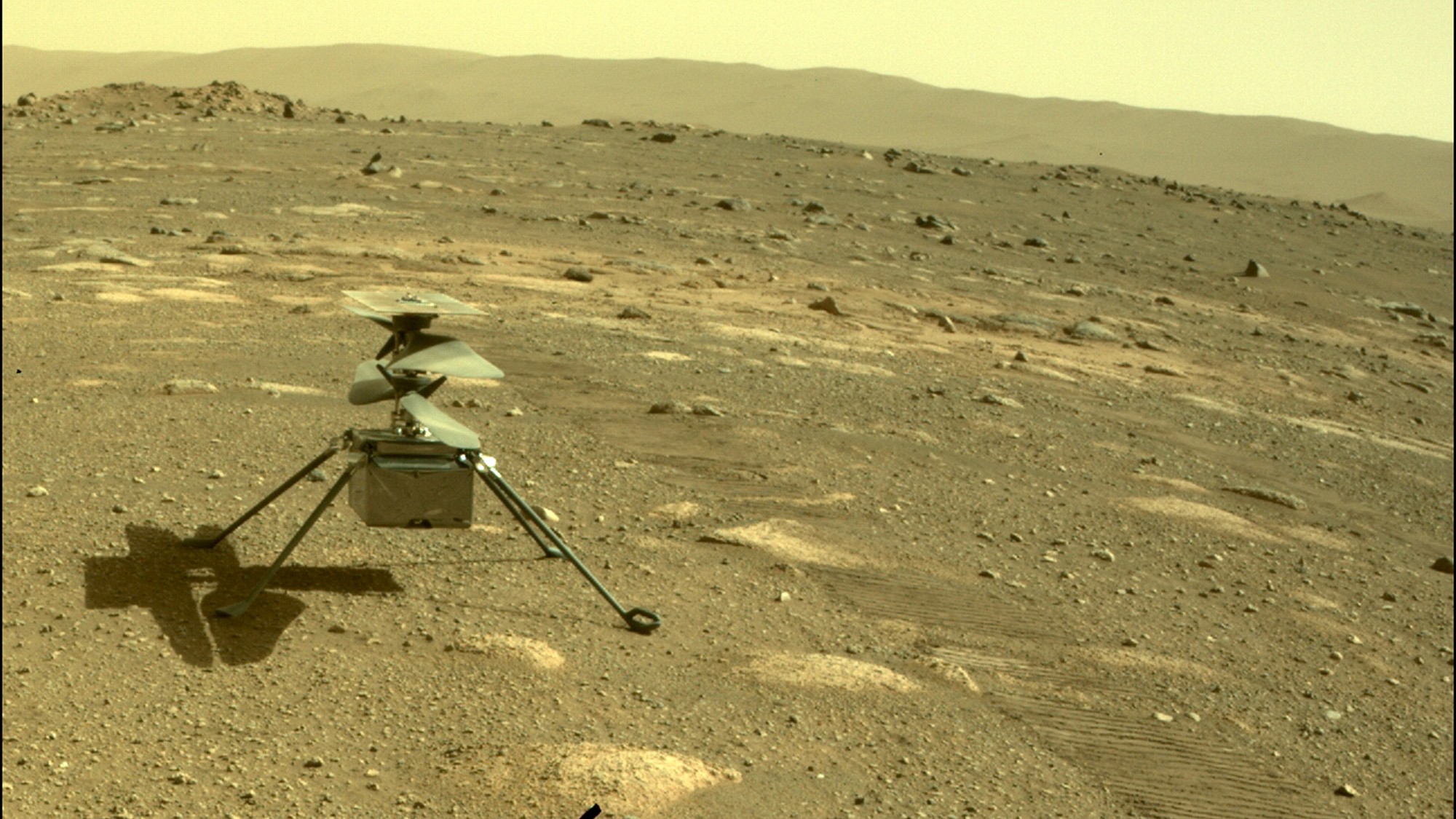

Perseverance, an improved version of Curiosity, has landed in the Jezero crater, a former river delta. It will also look for signs of past life: seeking out biosignatures left by microbes. The rover is the first part of a “sample return” project: it will store rocks and samples which a later mission will return to Earth for further analysis, if all goes to plan, in 2031. Perseverance also aims to prepare for future human missions to Mars. It will attempt to synthesise a small amount of oxygen from the carbon dioxide that makes up 96% of the Martian atmosphere. In a few months it will fly a drone, the Ingenuity helicopter – the first time humans will have launched powered flight on another planet. The idea is that it will act as a scout, helping to plan routes for future missions.

When is a crewed mission likely?

Nasa aims to send astronauts to Mars by 2030, an objective it describes as “humanity’s next giant leap”. Elon Musk, founder of the space exploration company SpaceX is even more boosterish: he is “highly confident” SpaceX will send humans to Mars by 2026, and hopes to have sent a million people there by 2050. The obstacles are formidable. At its closest, Mars is 33.9 million miles from Earth; a journey that takes a spacecraft about seven months. The most difficult part of any mission is landing on its surface – a process known as the “seven minutes of terror”. Slowing a spacecraft down from about 12,000mph to landing speeds in Mars’s thin atmosphere is vastly complex: Perseverance used a heat shield, then a parachute, then a sky crane – an apparatus equipped with retro rockets which separates from the rover, and lowers it onto the planet floor. Landing one-tonne rovers is an amazing feat. Landing astronauts, plus their equipment and supplies, plus a spacecraft and fuel for return, is quite another question.

What about the longer term?

For Musk and others, the aim is to build colonies on Mars: we need to become a “multi-planet species”, he says, rather than “hanging out on Earth until some eventual calamity claims us”. Whether becoming a two‑planet species will do much for humanity’s survival is a moot point, when the second planet is as brutally hostile as Mars. But at the very least, many envisage small but viable colonies and a space tourism industry there in the coming decades. For most space scientists, though, the real objective remains the discovery of life. Finding a “second genesis of life” besides the one on Earth – and in our own backyard – would have profound scientific and philosophical implications: it would suggest that life exists throughout the universe.

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?

-

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottages

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottagesThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in West Sussex, Dorset and Suffolk

-

The week’s best photos

The week’s best photosIn Pictures An explosive meal, a carnival of joy, and more

-

How Mars influences Earth’s climate

How Mars influences Earth’s climateThe explainer A pull in the right direction

-

Blue Origin launches Mars probes in NASA debut

Blue Origin launches Mars probes in NASA debutSpeed Read The New Glenn rocket is carrying small twin spacecraft toward Mars as part of NASA’s Escapade mission

-

Panspermia: the theory that life was sent to Earth by aliens

Panspermia: the theory that life was sent to Earth by aliensUnder The Radar New findings have resurfaced an old, controversial idea

-

NASA reveals ‘clearest sign of life’ on Mars yet

NASA reveals ‘clearest sign of life’ on Mars yetSpeed Read The evidence came in the form of a rock sample collected on the planet

-

Answers to how life on Earth began could be stuck on Mars

Answers to how life on Earth began could be stuck on MarsUnder the Radar Donald Trump plans to scrap Nasa's Mars Sample Return mission – stranding test tubes on the Red Planet and ceding potentially valuable information to China

-

Mars may have been habitable more recently than thought

Mars may have been habitable more recently than thoughtUnder the Radar A lot can happen in 200 million years

-

Why water on Mars is so significant

Why water on Mars is so significantThe Explainer Enough water has been found to cover the surface of the Red Planet – but there's a catch

-

Liquid water detected on Mars raises hopes of life

Liquid water detected on Mars raises hopes of lifeSpeed Read A new study suggests huge amounts of water could be trapped beneath the surface of Mars