What’s driving India’s fake news problem?

Research by BBC links spread of misinformation to nationalism

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The BBC is launching an international initiative to tackle the spread of “fake news” and misinformation across the globe.

The project kicks off today with the Beyond Fake News conference in the Kenyan capital city of Nairobi, where the broadcaster is sharing the results of research based on in-depth analysis of messaging apps in India, Kenya and Nigeria.

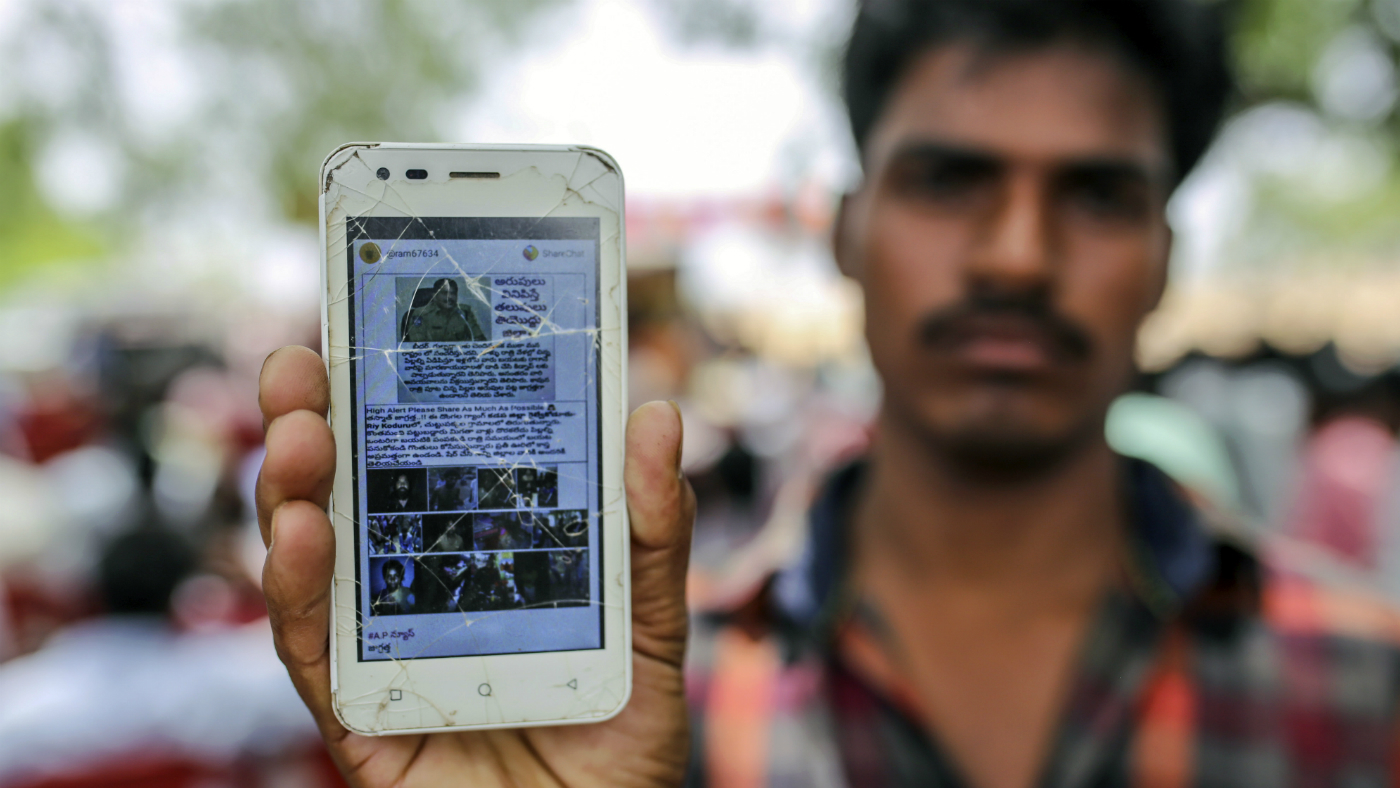

India, in particular, appears to be in the grip of a fake news crisis. The BBC’s research found that many Indian social media users “made little effort to figure out the original source for what they shared”, reports Quartz.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The consequences have been serious and even fatal.

How is fake news spreading in India?

The BBC’s research used multiple methods to understand the circulation of fake news, including interviews and the analysis of 16,000 Twitter profiles and 3,200 Facebook pages, along with WhatsApp messages shared by 40 volunteers.

WhatsApp appeared to be the main driving force behind the spread of fake news in India. Fuelled by a distrust of mainstream news outlets, Indians are spreading information from alternative sources without verifying it. In doing so, they believe themselves to be promoting the “real story”, says Quartz.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Based on survey responses, the BBC found that many Indians “relied on markers like the kind of images in a message or who sent it to them” in order to decide “if it was worth sharing”.

As a result, messages from close friends and family members were often assumed to be trustworthy, regardless of whether they actually were.

Why is it spread?

Messages “centering on the ideas of nationalism and nation-building” were the most commonly shared fake news items, reports the Hindustan Times.

The BBC says that fake news is a central component of a “rising tide of nationalism” in which “facts were less important to some than the emotional desire to bolster national identity”.

The research found that there was also an “overlap” of fake news sources on Twitter and support networks of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

“The results showed a strong and coherent promotion of right-wing messages, while left-wing fake news networks were loosely organised, if at all, and less effective,” the broadcaster adds.

Jamie Angus, director of the BBC World Service Group, said: “Whilst most discussion in the media has focused on ‘fake news’ in the West, this piece of research gives strong evidence that a serious set of problems are emerging in the rest of the world where the idea of nation-building is trumping the truth when it comes to sharing stories on social media.”

What are the consequences?

According to a separate BBC analysis, “at least 32 people have been killed in the past year in incidents involving rumours spread on social media or messaging apps”.

In July, five men were lynched by a mob in a rural Indian village over false child kidnapping accusations spread via WhatsApp. More than 20 people were arrested over the killings.

Quartz reports that in response, the Indian government has “issued stern warnings to the Facebook-owned messaging service”, which has “limited the number of times a message can be forwarded in the country”.

But with national elections due to be held in April or May, the political consequences of fake news could be significant - and to “blame social media and WhatsApp would be to shoot the messenger”, says The Indian Express.

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’Feature A grim reaper for software services?

-

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC head

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC headSpeed Read Jay Bhattacharya, a critic of the CDC’s Covid-19 response, will now lead the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

EU and India clinch trade pact amid US tariff war

EU and India clinch trade pact amid US tariff warSpeed Read The agreement will slash tariffs on most goods over the next decade

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire