Brazil's president isn't so bad. But her impeachment could be great for the country.

Finally, Brazil is starting to hold its dirty politicians accountable

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

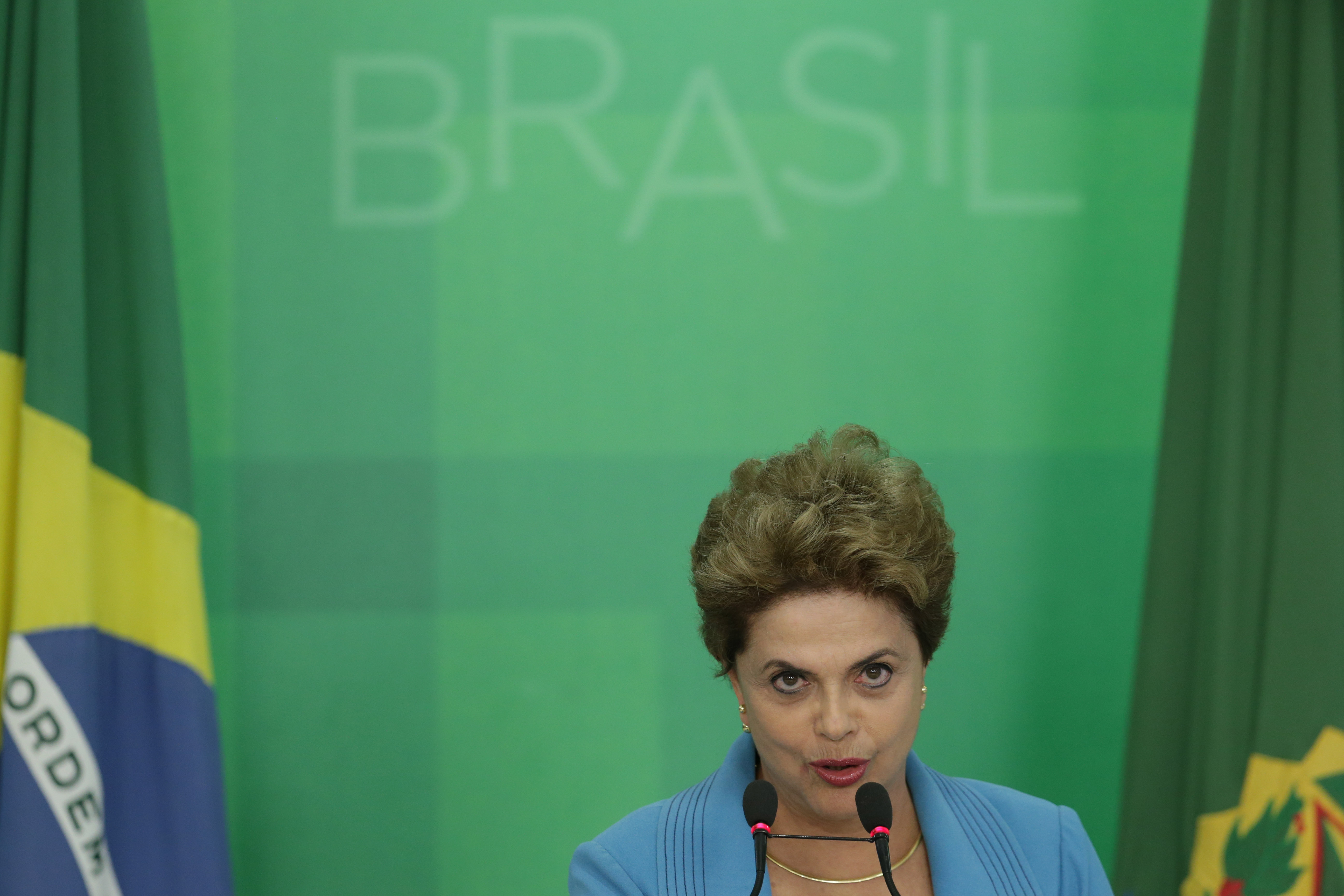

This week, Brazil's lower house voted to impeach the country's president, Dilma Rousseff, on nebulous charges of fudging deficit numbers to gain reelection. While Rousseff has vowed to stand her ground, the motion now goes to the country's Senate, where it could very well be approved, and her tenure cut short.

In a way, that would be unfair, because Rousseff is far from being the dirtiest politician in Brazil. Indeed, she hasn't been a bad president, having mostly sought to continue her predecessor's reasonable policies of mild social spending financed by a relatively unregulated (at least for Latin America) economy.

Still, her fall could be the first step in a long-overdue movement to hold Brazil's political elite accountable, and stem corruption before it spreads like a weed.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Corruption is a recurring theme in Brazilian politics. Indeed, the majority of the members of Brazil's Congress are either facing charges or being investigated for corruption or related crimes.

That is not a typo. Here are the actual numbers:

Of the 513 members of the lower house in Congress, 303 face charges or are being investigated for serious crimes. In the Senate, the same goes for 49 of 81 members. [Los Angeles Times]

Even Rousseff's vice president, Michel Temer, who would succeed her in the case of an impeachment, is by some reckonings more corrupt and unpopular than she is.

Meanwhile, Brazil is in the throes of the biggest scandal in the country's history. Petrobras, Brazil's biggest, and state-owned, oil company, has been running a slush fund to bribe politicians for over a decade. While there's no clear evidence Rousseff knew about the bribery, her party, the Workers' Party, was shown to be involved, as was her predecessor, Lula da Silva, who has been indicted for corruption.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

All of this, combined with a slowing economy and the growing rift between the country's haves and have-nots means Brazilian society is really angry. As a country with a plantation and colonial history, Brazil has often been ruled by a narrow, plutocratic elite. The country is plagued by poor infrastructure, poor public services, poor education, and rotten favelas. Even though the country is now a democracy, many Brazilians still feel disenfranchised. They feel that insiders, whether politicians, businessmen, or the media, control the system and rig it against the little guy.

Rousseff is taking the fall for this voter outrage, which is unfortunate for her, but good for her country.

The most precious ingredient in any political culture is accountability. Dirty politicians exist everywhere, but where accountability exists, corruption cannot metastasize. When leaders screw up, are they held accountable? In Brazil, the answer has too long been "no," which is what makes Rousseff's impeachment so potentially groundbreaking. It means Brazil is taking a groping step towards building a culture of accountability. And that's what it needs most.

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes, The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places. He lives in Paris with his beloved wife and daughter.

-

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surge

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surgeIN THE SPOTLIGHT Mass arrests and chaotic administration have pushed Twin Cities courts to the brink as lawyers and judges alike struggle to keep pace with ICE’s activity

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax

-

‘The West needs people’

‘The West needs people’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military