Buffy the Vampire Slayer is the greatest show in the history of television

It shattered my innocence, and forced me to grow up

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Some time ago, I compiled a writing playlist comprised of my favorite instrumental pieces. Propelled by instinct rather than reason, I included "Sacrifice," the music that concludes the fifth season of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. My husband watched with mild bemusement as I clicked and dragged the file to a place of prominence within the mix. "Are you sure you want to listen to 'Sacrifice' while you're trying to work?" he asked. "You cry every single time."

If you're familiar with season five's finale, entitled "The Gift," you know that my husband's reservations were not misplaced. This is the episode in which Buffy Summers (Sarah Michelle Gellar) swan dives into the gaping maw of a demonic vortex: a heroic act that saves the world (again) — and ensures her death.

These circumstances would be tragic on their own, but an interwoven narrative thread creates a one-two punch of heartbreak. Buffy could have averted martyrdom, but only if her little sister Dawn (Michelle Trachtenberg) had died in her stead. The moment Buffy realizes that she can take Dawn's place, the first elegiac notes of "Sacrifice" resound, tender but purposeful. As the scene moves swiftly to its apex — Buffy kisses Dawn and leaps into the void — the score follows, swelling in anguish. It is an exquisite and unflinchingly bleak finale, and if the music elicits a hearty cry on its own, you can imagine the emotional wallop of the scene.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A confession: I've referenced it in therapy more than once.

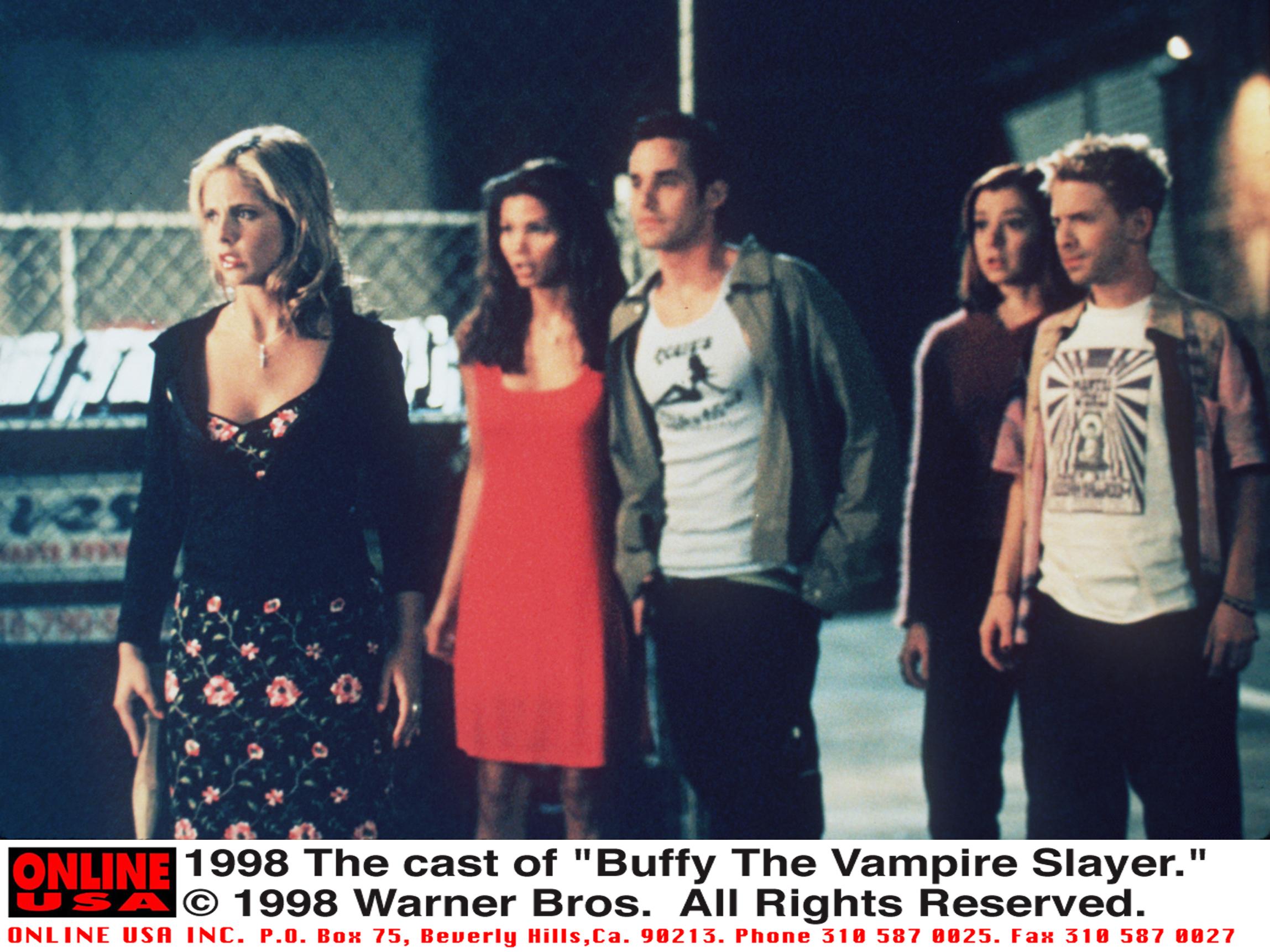

Buffy the Vampire Slayer — which debuted exactly 20 years ago today, on March 10, 1997 — stole my anxious heart in junior high. The prevailing theme — growing up is hell — was resonant, and I delighted in the brilliantly over-the-top metaphor. I was moreover seduced by Joss Whedon's trademark brand of caustic elegance. Buffy and her pals always seemed to know precisely what to say — not always to each other, mind you, but to illuminate the absurdity or pathos of a particular moment. I was unconcerned with whether such a polished script rendered the dialogue less organic; besides, the cast's delivery was nearly always compelling. As a literary dreamer who was always trying to say it right, those who could and did dazzled me.

And of course there were the core characters themselves: Undone by their foibles, but braver than most, some of them almost Dickensian in specificity. I was charmed by the way Willow Rosenberg (Alyson Hannigan) buoyed her words with shallow little breaths whenever she was pleased, but a bit flustered. I mourned the calamity of the chenille pink sweater — with those woeful daisy accents! — and loved her more vigorously. I longed to coo "Bored now," like her demonic alter-ego, and hurl school bullies across the lunchroom. In another two decades I would understand in more sexually mature terms just why I was so drawn to Willow, and why I rejoiced when she and Tara (Amber Benson) coupled in tender romance. At the time, I just cherished a plotline in which two weird girls were adored for being perfectly themselves.

As for Buffy, well, I didn't want to love her — after all, I wanted to be her. This veneration rendered her ineligible as a fictional kindred spirit. In fact, designating her as such almost seemed presumptuous. A prickling shame fizzles in your gut when you draw parallels between yourself and a character that makes you jealous. Name aside, Sarah Michelle Gellar's Buffy seemed the perfect alchemy of beauty, wit, and superhero puissance. Ever the Type A, I was agitated by her irregular school attendance, but no matter: Robust SAT scores and the golden kiss of fiction resulted in her acceptance to top-tier universities.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Intellectually, I always understood that Buffy's supernatural burden was not to be envied. Born from ancient rites of patriarchal exploitation, the Slayer is thrust to society's margins where she engages in a lonely, thankless war against evil. Her solitude ensures the safety of her community; she serves as peril's polestar, drawing the bloodthirsty away from those who cannot fathom their existence. A slayer, then, is unlikely to forge many intimate relationships. She's unlikely to survive past early adulthood.

But Buffy tenaciously seeks compatibility between her shadow life and an adolescent's quotidian existence. She keeps close to a circle of friends and occasionally attempts to date men who are not vampires. She tries out for cheerleading, attends the senior prom, and goes to college. And yet, she is dogged by irrefutable discordance. Throughout its seven seasons, the show articulates a fundamental conflict between a world that thrives on convention and another whose logic is always unfurling. Sometimes they collapse into the same dimension, but regardless, destiny has selected Buffy to be the guardian at the threshold.

She is thus compelled to sacrifice at every turn, across a spectrum of magnitude. In the first season, she can only attend the high school dance if she survives her foretold battle with a primordial vampire. Despite her many college acceptances, she must remain in Sunnydale to fulfill her duties. At base, Buffy exemplifies the paradox of the superhero: Her life both enchants and repels. Vicariously, we relish the grandiosity and imagine the satisfaction that accompanies intensified triumphs, passions, even struggles. But when the episode ends, we are relieved to be free from otherworldly burdens. We remember that we do not have to save the world by ourselves.

It is all too easy to romanticize the impossible. For years, my view of Buffy Summers was filtered through alchemized resentment and marvel. Because I was adolescent, self-centered, and unlikely to be tasked with slaying a vampire, my imagination glossed over Buffy's highly particular set of tribulations. And as a result, her life seemed preferable to my own. Hell, it even seemed easier. How could you suffer, really, when everyone was always falling in love with you? When your surrogate father was an adorably stuffy and tweed-blazered Brit. When you were unafraid to tell those who deserved it to f--- off (in, of course, parlance suited to the WB's profanity guidelines). Envy rendered me superficial and vacant of empathy.

Then, on May 22, 2001, "The Gift" aired. Buffy died. Despite my habitual outpourings of emotion, I was startled by my own tears, and baffled as they gave way to sobs. My stomach had tightened into a marble-sized knot. I wandered into the kitchen and encountered my father, who started at my chaotic appearance. Not a little alarmed, he demanded to know what had happened. "B-Buffy is d-d-dead!" I blubbered. This response did not elicit much sympathy and, to be fair, even I thought I was overreacting. A sixth season of BTVS had been confirmed; the central character's death was bound to be temporary (given the show's fantastical bend, I could safely make this assumption). But to this day, no scene in television or in cinema has shattered me so thoroughly. I can hardly call it to mind with dry eyes.

It sounds maudlin to say I learned that night what it meant to love Buffy or, more generally, the show, and anyway, that's not precisely it. In fact, for years I chalked up my devastation to maniacal hormones and newfound sympathy for a character I had tried not to like. It is true that I wholly succumbed to Buffy after watching "The Gift." I dispensed with my petty jealousies and became her fierce champion. It is also true that my affection was to some degree born from admiration. I thought of my two younger sisters and swiftly felt ashamed that I did not think of them more. And yet, intermingled with that shame were pulses of wild, red love. They both lived in my bones, my sisters. There is no cord delicate enough to trace our kinship; we are stacked, tangled, lapped. Every time I watch "The Gift" I am tempted to call them, to declare my fidelity through tears and a fevered throat. "I love you so much I'd jump into a demonic vortex to save you," I'd say. But I never have, perhaps because I know it's impossible to make good on my vow.

This impulse no doubt springs from delusions of grandeur even as it is quickened by love. But there's one more catalyst: fear. When I watched "The Gift," it was with the thick selfishness of someone who had never mourned. My world was structured according to the tacit assumption that youth shielded me from loss — that for all intents and purposes, everyone I knew and loved was immortal until some obscure day when I would be old enough to suffer their absence. When Buffy jumped to her death, my lizard brain whispered, "Survival is not default." Happenstance and a healthy bulk of privilege had fomented a cozy mythology: Nothing consequential was required of me because time had not permitted it, not yet.

As the Scoobies approached the body of their heroic friend, as a bleeding Dawn staggered toward her sister, my mythology cracked wide open. No net cradled my world, lest it fell. Nothing safeguarded me from all the things I wasn't prepared to feel. Pain would find me — or I would be forced to choose it — but, in the meantime, there was life and the people in it. In the meantime, I could love them.

Rachel Vorona Cote is a writer in Washington, D.C. She is a contributor at Jezebel and has written for other venues including The New Republic, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Hazlitt, and Literary Hub. You can find her on Twitter here.