Why is President Trump letting the Saudis push him around?

America's moral authority isn't at stake in Saudi Arabia. Its practical authority is.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

President Trump famously hates to look weak. So why is he letting Saudi Arabia push him around?

The alleged murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi by Saudi intelligence agents would seem to provide ample justification for a harsh rebuke, if not something stronger. Khashoggi was an American resident, and he appears to have been killed within the Saudi consulate in Turkey. A more blatant violation of diplomatic norms would be hard to imagine. If the Saudis can just get away with that, the White House would seem to be saying they can get away with anything.

And at first, that's precisely what the administration seemed to be saying. Trump's initial concern was that sanctions would sabotage American arms sales. His deeper interest is the desire to preserve a united regional front against Iran. And, to be fair to the president, there's a long tradition of American obsequiousness toward the Saudi kingdom: President George W. Bush didn't break with them over 9/11, nor did President Barack Obama over their support for ISIS. Across the decades, the Saudis have proven extraordinarily adept at navigating a changing world, and at soothing Washington's sensitivities.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

There isn't much soothing going around this time, though. The Saudis initially refused to even take seriously international concerns about Khashoggi's fate. And as the conversation turned to sanctions, the kingdom's swaggering Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman leveled pointed threats to retaliate by turning off the oil spigot and sending the world economy into recession.

If this were the behavior of an adversary, like Russia or North Korea, one might argue for a measured response, to prevent the conflict from escalating beyond either party's control. If this were the behavior of a vital ally against a far more dangerous enemy, one might make the case for putting moral considerations on the back burner, as FDR did with Stalin during World War II, and as Nixon did with Mao to effect a split in the communist bloc.

But Saudi Arabia is neither a powerful enemy nor a vital ally. It's a client, dependent on American protection for its very survival. If America were to deny it arms, it couldn't simply switch to Chinese or Russia suppliers, because our weapons are not inter-operable. Saudi Arabia's brutal and failing war in Yemen — which looks likely to trigger the worst famine in that country in a century — is far more serious than the murder of a single journalist and is being prosecuted with active American support for the Saudi air force. But that war serves no American interest at all; indeed, our support was originally provided — by the Obama administration — to placate the Saudis, who feared an American tilt to Iran after the nuclear deal.

Given their dependence, we should have far more leverage over their behavior than we do. Instead, they are flaunting their leverage over us by threatening to unleash the oil weapon they deployed so dramatically in 1973 after Israel's victory in the Yom Kippur War (and, in reverse, in 1986, when they opened the spigots to help bankrupt the Soviet Union). But America is no longer dependent on Gulf oil as we were in decades past. If Saudi Arabia allowed oil prices to skyrocket, it would empower its largest regional adversary — Iran — and encourage importing countries to seek long-term relationships with more reliable suppliers, or to accelerate their transition away from oil entirely. And a recession would trigger a collapse in demand that would ultimately hurt its own bottom line, which they could hardly afford when their Yemen debacle is costing them billions per month.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The kinds of arguments Trump himself has levied against our alliances with South Korea or Germany apply with far greater force to our relationship with Saudi Arabia. And if it is easy to win a trade war with China, as Trump claims it is, it should be a piece of cake to win a staring contest with Saudi Arabia.

Even Pat Buchanan, one of Trump's strongest intellectual defenders, thinks this is one time America shouldn't put its conscience on the shelf, but instead take the opportunity to back away from a relationship that has long since ceased to serve American interests.

So why aren't we?

What's at issue isn't ultimately America's moral authority. It's our practical authority — whether we or Saudi Arabia are the dominant player in our relationship. That's a language Trump of all people should clearly understand.

The Trump administration has put a lot of chips down on the relationship with Saudi Arabia. But those are Trump's chips, not America's. And he's supposed to put America first.

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.

-

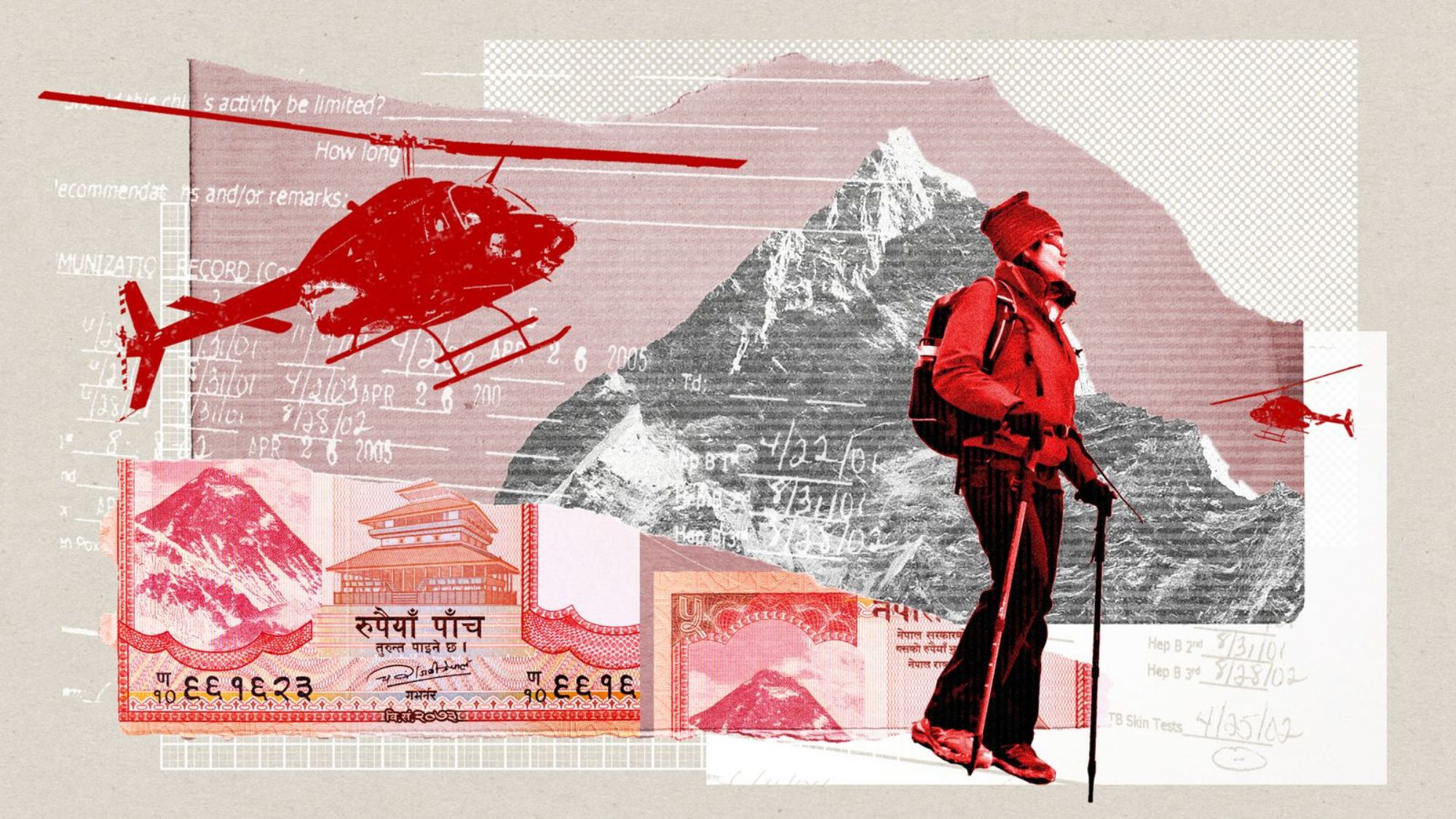

Nepal’s fake mountain rescue fraud

Nepal’s fake mountain rescue fraudUnder The Radar Arrests made in alleged $20 million insurance racket

-

History-making moments of Super Bowl halftime shows past

History-making moments of Super Bowl halftime shows pastin depth From Prince to Gloria Estefan, the shows have been filled with memorable events

-

The Washington Post is reshaping its newsroom by laying off hundreds

The Washington Post is reshaping its newsroom by laying off hundredsIn the Spotlight More than 300 journalists were reportedly let go

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military

-

How Bulgaria’s government fell amid mass protests

How Bulgaria’s government fell amid mass protestsThe Explainer The country’s prime minister resigned as part of the fallout