The televised debate stage: A history

It used to be so civilized ...

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In American politics, optics are everything. From a candidate's logo to what they wear to how or when they drink water, even the most insignificant gestures, facial expressions, and color choices can become the topic of intense scrutiny.

It should be no wonder, then, that since the advent of television, our presidents have included a movie star, an attractive playboy, and a reality TV host. Yet the physical appearance of a candidate is only one element in the making of the presidential image. How and where we show politicians doing the work of politicking is of equal — and sometimes even more — consequence.

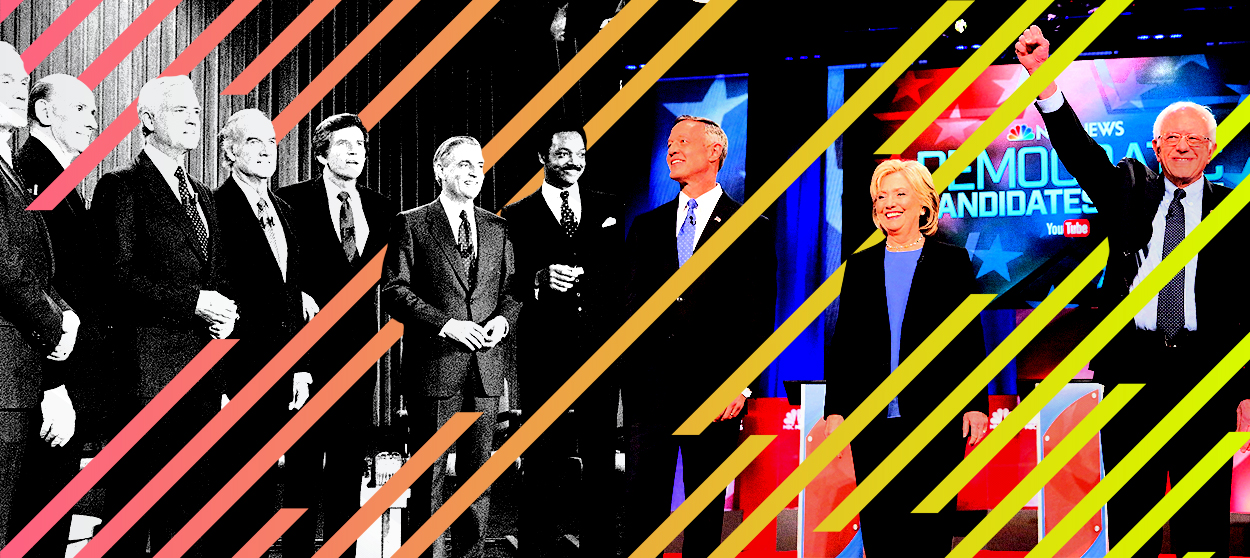

The debate stage, like the one in Miami where nearly two dozen Democratic hopefuls will stand in their first test for the 2020 nomination on Wednesday and Thursday night, is as crucial to establishing the tone of an election cycle as the first barb thrown between candidates. And while the format, candidates, and networks will vary in the months ahead, there are certain things you can be sure to expect: countdown clocks, ads that make you half-expect the candidates are going to come to blows on stage, and decor that looks like someone put an American flag in a blender and then blindly splatter-painted the results on the wall.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It wasn't always this way.

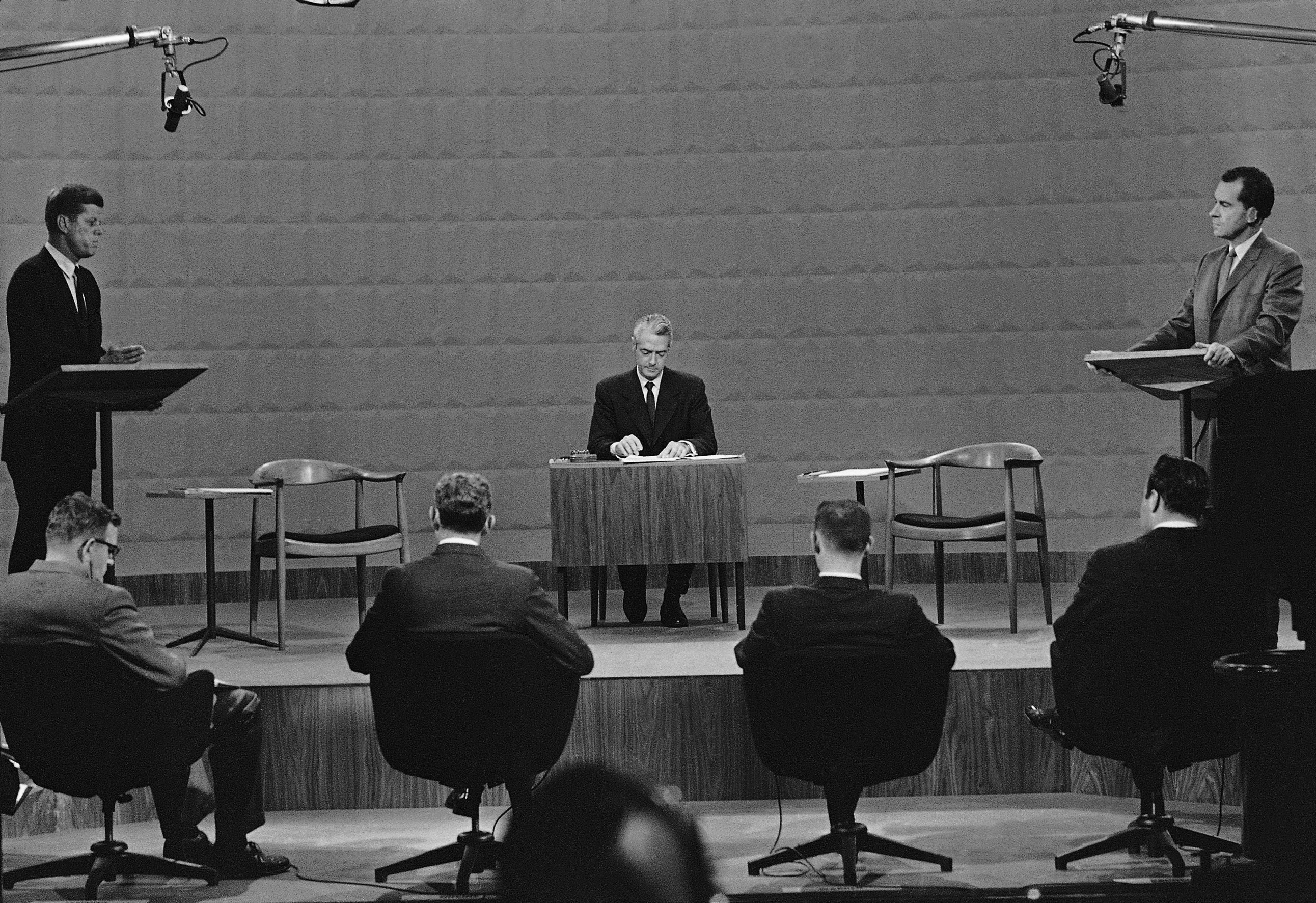

When it comes to the question of the first televised presidential debate, the typical crossword puzzle answer is the famous 1960 matchup between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. But that answer is technically wrong. The first televised presidential debate stage actually debuted four years earlier, in CBS' Face the Nation studio, when Democrat Adlai Stevenson challenged Republican incumbent President Dwight Eisenhower in 1956. Instead of appearing themselves, however, the two candidates went head-to-head via surrogates, much the way vice presidents do during the general election now. For the Democrats, former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt stepped up to the plate; for the Republicans, Maine Sen. Margaret Chase Smith. While this week's Democratic debates will host the most female candidates in a presidential primary ever, it was women who actually stood on the first broadcast debate stage with nothing more than a black backdrop behind them.

For years, the appearance of the debate stage wasn't much of a consideration, although that didn't mean the studio spaces where the debates were recorded weren't consequential — Nixon's poor suit choice in the 1960 debate awkwardly blended him into the background at CBS' WBBM-TV in Chicago (as you can see above). The studio debates also helped establish the image of "dueling" politicians, who stood at podiums facing each other but far enough apart to add some theatricality and performance. This would become the predominant arrangement for American political debates, with occasional exceptions, such as when Robert Kennedy and Eugene McCarthy would debate each other in a 1968 "semi-formal" primary while seated at a table — a more natural and less performative mode of discussion.

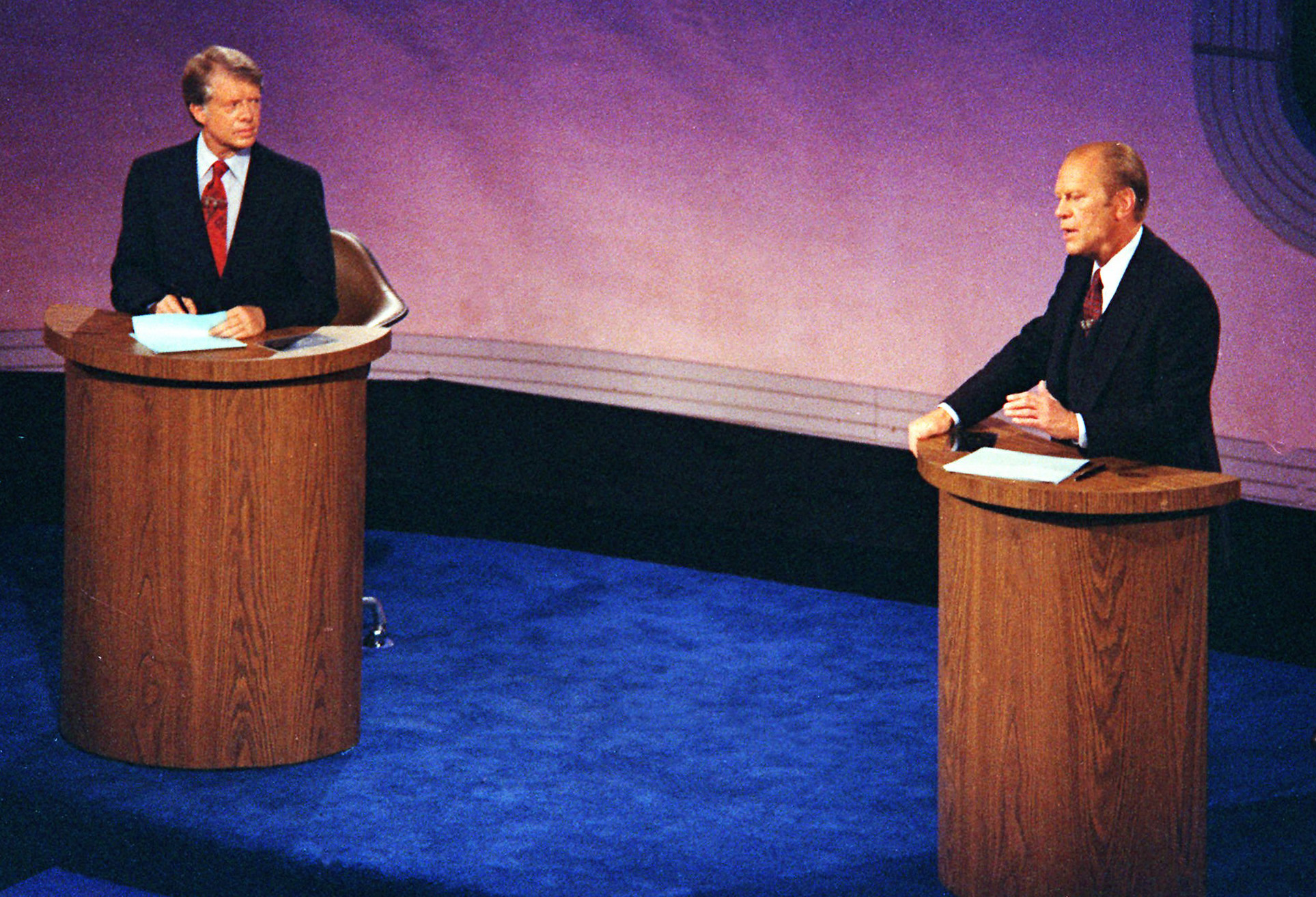

In 1976, the League of Women Voters sponsored a debate between Democratic candidate Jimmy Carter and Republican incumbent President Gerald Ford, held not in a television studio but on location for the first time, at the Walnut Street Theatre in Philadelphia. Standing on a plain blue carpet, facing a live audience of around 500 people (200 of whom were journalists) and an anticipated TV audience of 90 million, Ford and Carter were forced to stop debate after 81 minutes when the sound went out.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Despite the technical difficulties, the studio debate format was now a thing of the past. Theaters, auditoriums, and universities had become the new home of the political debate.

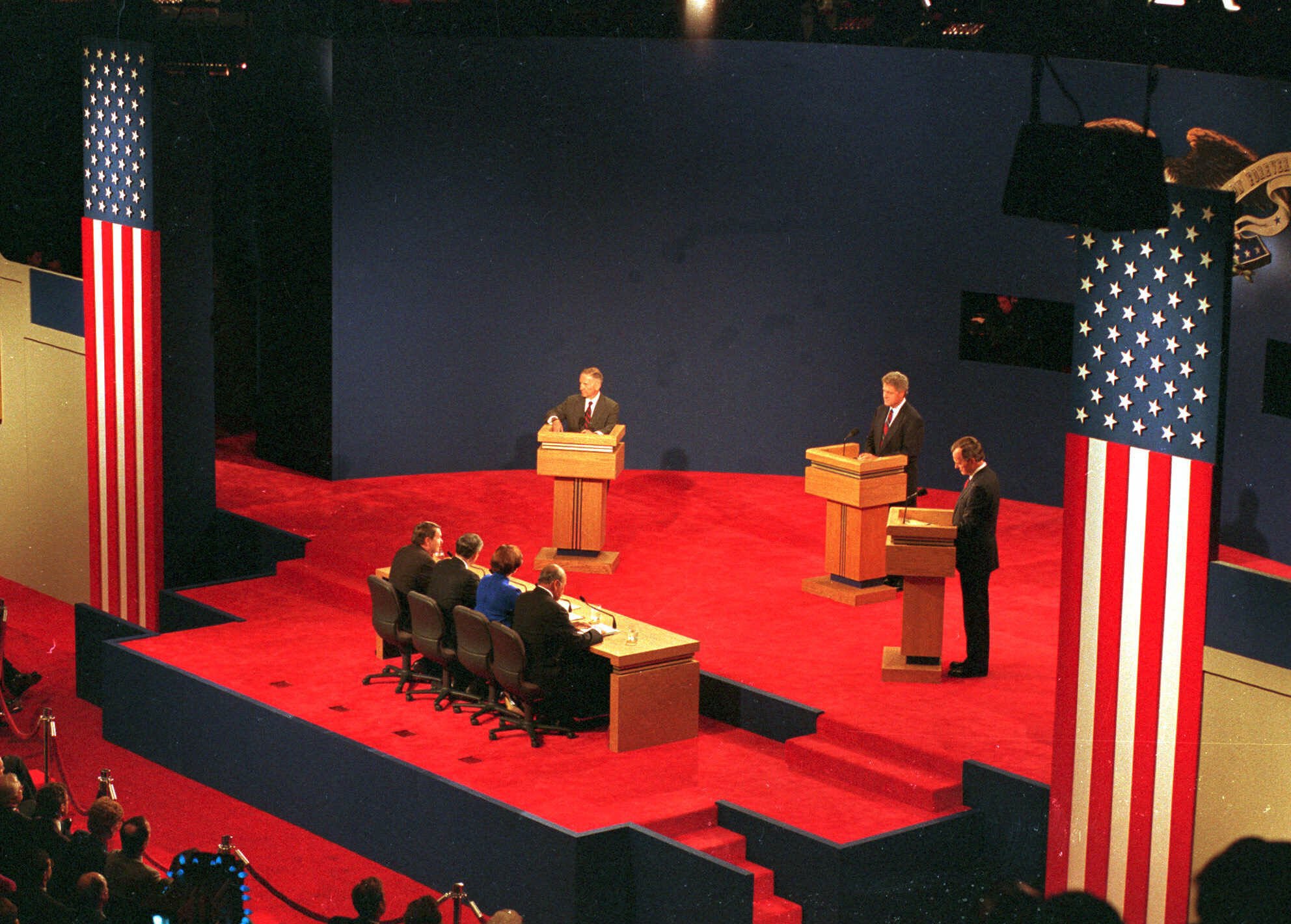

By the time incumbent President George W. Bush, Bill Clinton (D), and Ross Perot (I) were debating at Washington University in 1992, studio debates had long fallen out of vogue. Still reigning supreme however was a minimalist stage decorated only with podiums and the occasional minor decorative flourishes like flags. But with color TVs in "nearly all of America's 94 million households" by 1992, the sense of pomp and pageantry on stage was growing

Political debate became, undeniably, a show after the turn of the millennium — and one verging on spectacle. One reason is that new technology made things like digital backdrops and special computer graphics possible. Still, that alone doesn't explain why networks got so extra with their coverage, making the debate stage look like a freeze-frame from The Colbert Report opening credits.

One Republican debate in 2015 even took place in front of Air Force One.

The over-the-top productions have largely been a product of a shift in our culture, with networks now fighting to capture distracted viewers not just by appealing to our civic duty, but by turning politics into entertainment akin with reality television, sports, and game shows. Just sub in "contestants" for "candidates" in NBC's teaser for the Democratic debates, which assures the drama of "20 candidates battling it out over two nights, all needing to break through" and the ad might just as easily be for Survivor or The Bachelorette.

Some critics have bemoaned the state of the modern debate, claiming network's high-gloss productions and candidates' months of preparation have instead made authenticity and spontaneity rarer and rarer. The debates have even been criticized as being nothing more than "competitive press conferences." It is no surprise, then, that President Trump stood out from the crowd in the 2016 Republican primary with his off-the-cuff, insult-lobbing debate performances, which fed off of the competitive, game show-like tone stoked by the networks.

There has long been a push, at an institutional level as well, to re-imagine what the debate stage could be. Speaking to The New York Times in 1992, NBC News anchor Tom Brokaw, "half-joking," proposed the candidates "come to my house. We serve them a martini. And we have an exchange between the two."

Hey, why not try something new?

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military