Brexit glossary: from max fac and Chequers to Norway and Canada +++

The Week's guide to all the jargon you need to know as the UK gets set to exit the EU

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The language of Brexit has proven almost as complicated as the process itself, with the House of Commons library even seeking a specialist Brexit editor to make sense of it all.

With less than six months to go before Britain leaves the EU, “the post has been created to give MPs and their staff the ‘information they need to scrutinise the Brexit process’ and help them make ‘well-informed decisions’”, according to The Times.

Here is just some of the jargon the new Commons employee will have to get their head around and some concise definitions by The Week:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Article 50

This is the formal mechanism for exiting the EU: the clause in the 2007 Lisbon treaty that allows any member state “to withdraw from the union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements”.

Withdrawal agreement

The UK and EU are negotiating a withdrawal agreement that will cover all parts of Britain's exit from the bloc, including the divorce financial settlement (or “Brexit bill”), Irish border and citizens' rights. It is “separate from any treaty on the UK's future relationship with the bloc, with the withdrawal agreement to be voted on by MPs at the end of the Brexit process”, says Sky News.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Canada +++ or Super Canada model

This potential model of Brexit, favoured by Boris Johnson and the hardline Brexiteers, is a free trade agreement like the one Canada has with the EU, but better (hence +++). Goods traded between the UK and EU have to be checked at the border but there wouldn’t be any import taxes. Brexiteers “want it because it takes the UK out of the EU’s orbit compared to now”, says The Independent, but it is not supported by Theresa May.

Norway model

Favoured by soft-Brexiteers, the Norway model offers an example of what it’s like to remain in the single market, but not be in the EU. The government's own impact assessment found the Norway option would be the least damaging in terms of economic harm but it would involve the UK being a member of the European Economic Area (EEA) and thereby accepting freedom of movement and laws of the market that are made in Brussels.

Chequers plan

Theresa May’s Brexit plan named after the Prime Minister's country residence, where it was agreed at a meeting of the Cabinet in July. It includes a “common rulebook” for all goods traded with the EU and a “facilitated customs arrangement”, which aims to maintain frictionless trade in goods but not services or workers, dividing the four freedoms of the EU which have remained the bloc’s red lines in negotiations.

Irish backstop

The backstop is a position of last resort and has been needed for the thorny issue of the Irish border. The challenge has been to find an arrangement that doesn’t derail the peace process by creating a hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland or between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK. May “wants a backstop that would see the whole of the UK staying in the customs union for a limited period of time after the transition period, something the EU has said is unacceptable”, says the BBC.

Max fac

“Max fac” - short for “maximum facilitation” - is a proposed customs system that “would rely on technological checks to maintain an open border” in Ireland, explains PoliticsHome. It is favoured by Brexiteers but critics say it would not solve the Irish border question as there would still need to be tariff checks on the border, a red line for the Irish government.

-

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 February

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?

-

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottages

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottagesThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in West Sussex, Dorset and Suffolk

-

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?Today's Big Question After rushing to praise the initiative European leaders are now alarmed

-

How corrupt is the UK?

How corrupt is the UK?The Explainer Decline in standards ‘risks becoming a defining feature of our political culture’ as Britain falls to lowest ever score on global index

-

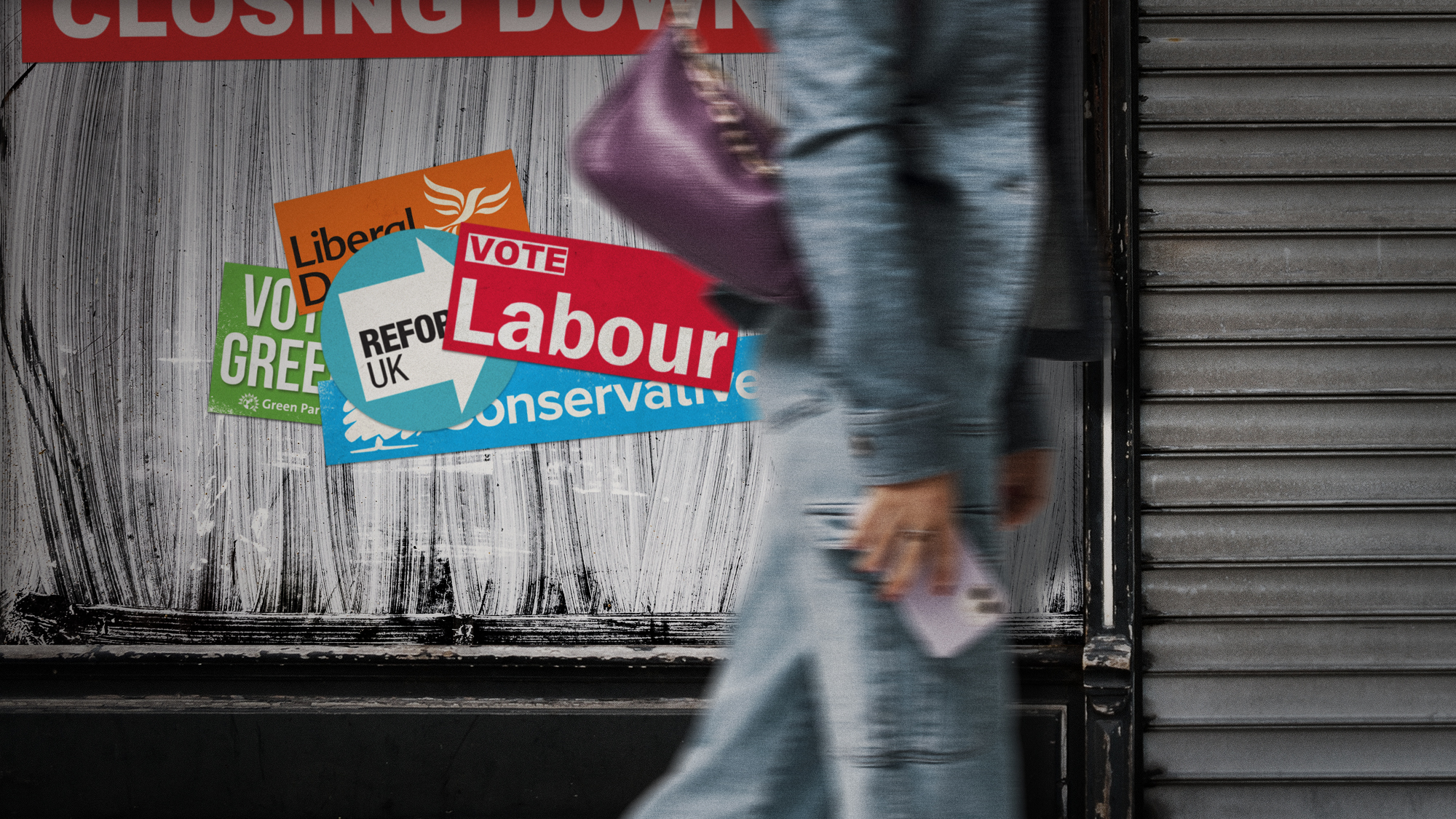

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?In the Spotlight Mass closure of shops and influx of organised crime are fuelling voter anger, and offer an opening for Reform UK

-

EU-Mercosur mega trade deal: 25 years in the making

EU-Mercosur mega trade deal: 25 years in the makingThe Explainer Despite opposition from France and Ireland among others, the ‘significant’ agreement with the South American bloc is set to finally go ahead

-

Biggest political break-ups and make-ups of 2025

Biggest political break-ups and make-ups of 2025The Explainer From Trump and Musk to the UK and the EU, Christmas wouldn’t be Christmas without a round-up of the year’s relationship drama

-

Who is paying for Europe’s €90bn Ukraine loan?

Who is paying for Europe’s €90bn Ukraine loan?Today’s Big Question Kyiv secures crucial funding but the EU ‘blinked’ at the chance to strike a bold blow against Russia

-

‘The menu’s other highlights smack of the surreal’

‘The menu’s other highlights smack of the surreal’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Moscow cheers Trump’s new ‘America First’ strategy

Moscow cheers Trump’s new ‘America First’ strategyspeed read The president’s national security strategy seeks ‘strategic stability’ with Russia