How to help Africa get COVID shots into arms

To beat COVID, Africa needs vaccines. And syringes. And helicopters. And generators.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The struggle to vaccinate Africa against COVID-19 grinds on. A few nations are finally making significant progress — Morocco is 60 percent fully vaccinated, South Africa 22 percent, and Rwanda 19 percent — but others have barely started. Cameroon is just 0.7 percent fully vaxxed, Chad 0.4 percent, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) a meager 0.05 percent.

There is still a dire shortage of vaccines across most of the continent. But supply is belatedly arriving, and in a growing share of countries the bigger bottleneck is administration. A lot of Africa is going to need help actually getting doses into arms. The rest of the world — and not just rich countries — can help.

The problems in the worst-off African countries are exactly what one would expect to find in places that were pillaged and dominated by foreign conquerors for 500 years. Take the DRC. It's no coincidence the sub-Saharan country is in last place in the vaccine race given its history of imperialist abuse. This was the site of a murderous frenzy of rubber and ivory looting that killed perhaps half its population from 1885 to 1908 under King Leopold II, followed by decades of rapacious Belgian rule focused mainly on mineral extraction, then a panicked colonial evacuation in 1960 that left just 30 college graduates to fill thousands of administrative and military officer posts. As the country fell into chaos, the U.S. and Belgium helped assassinate the elected Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba, after which Washington backed the wretchedly corrupt dictator Mobutu, who ruled until 1997.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That history is one reason I tend to be wary of foreign aid projects, which too often imitate the colonialist mindset and add to corruption and dysfunction instead of alleviating them. Still, public health efforts specifically have a pretty good track record. Africa had some of the last reservoirs of smallpox, but international efforts helped eradicate it in the 1970s. PEPFAR, a State Department program, has done a great deal to fight the AIDS epidemic in southern Africa. A combination of governments and philanthropists are on the verge of eradicating guinea worm entirely. Distribution of bed nets has made a good-sized dent in malaria, and former President Barack Obama helped coordinate the containment of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa from 2014 through 2016.

So what do places like the DRC and Chad need today? Obviously, I am not a vaccine distribution specialist, but a rough idea of what is needed can be found in how international agencies eradicated smallpox through mass vaccination. First, we'll need some workarounds to access areas without good transportation infrastructure, clean water supplies, and reliable electric power. Unfortunately, unlike the smallpox vaccine, thus far coronavirus shots require cold temperatures, so without refrigerators, power, and sanitary water, it's nearly impossible to run a vaccine clinic. (Missing basic stuff like this is the main reason why the DRC had to return 1.3 million vaccine doses back in April.) Generators, solar panels, and batteries can provide the power, however, while off-road trucks, planes, or helicopters can get past bad roads, and tents can serve as makeshift buildings.

We'll also need medical personnel and equipment. Administering vaccines is pretty simple, and most African countries probably have enough nurses and doctors to run mass vaccination clinics. But those folks may need training in how these particular vaccines should be stored and injected, and some countries may also need more personnel, especially in far-flung rural areas.

A bigger problem is syringes. As Janice Kew writes at Bloomberg, this is already the main bottleneck in countries like Rwanda, where the government was quite good at using up its vaccine supply until it ran short of needles and plungers. Africa has no syringe factory on the continent, and rich nations are being stingy with donations. Wealthier nations need to pony up more syringes in the short term and expand manufacturing supply as quickly as possible.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The third obstacle is ideological. There is reportedly a lot of vaccine hesitancy across Africa, some thanks to distrust in Western medicine and some due to anti-vaccine propaganda campaigns. As I wrote previously, the former president of Tanzania fulminated against COVID vaccines as some kind of white imperialist plot until he caught the virus himself and died. His successor has struggled to distribute the million doses Tanzania has received.

So far the solutions I've been outlining would be most easily carried out by rich counties. But when it comes to defusing antivaccine conspiracy theories, Americans or Europeans are probably less credible voices than folks from Asia, Latin America, or indeed Africa itself. There are plenty of respected, credentialed doctors and scientists from all over the Global South who can lean against conspiratorial narratives by simple virtue of their diversity.

Conversely, while rich countries can afford more helicopters and generators, those things aren't that expensive either — middle-income countries can pitch in too. African countries like Gabon, Botswana, South Africa, and Algeria are prosperous enough to help their neighbors, though of course they couldn't shoulder a continent-wide vaccination campaign alone.

My aim here is not to outline a detailed plan for vaccinating all of Africa. Real experts could do that much better. My point is that much of the continent will need outside help to have a prayer of getting fully vaccinated. The DRC has a population around 100 million, the 15th largest on the planet, and something like 1,900 miles of paved road in total (compare to over 98,000 in South Africa).

As I've argued over and over, it is gravely immoral for the rest of the world to let most of a continent go unvaccinated, and it is hideously short-sighted because of variant risk. The longer the world lets the pandemic fester, the more chances the coronavirus has to mutate into something that gets around the vaccines. It would be worth paying virtually any price to head off that possibility.

The international community has to get its act together and step up for Africa. There is no other sensible choice.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancer

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancerUnder the radar They boost the immune system

-

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the rise

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the riseThe Explainer ‘No evidence’ new variant is more dangerous or that vaccines won’t work against it, say UK health experts

-

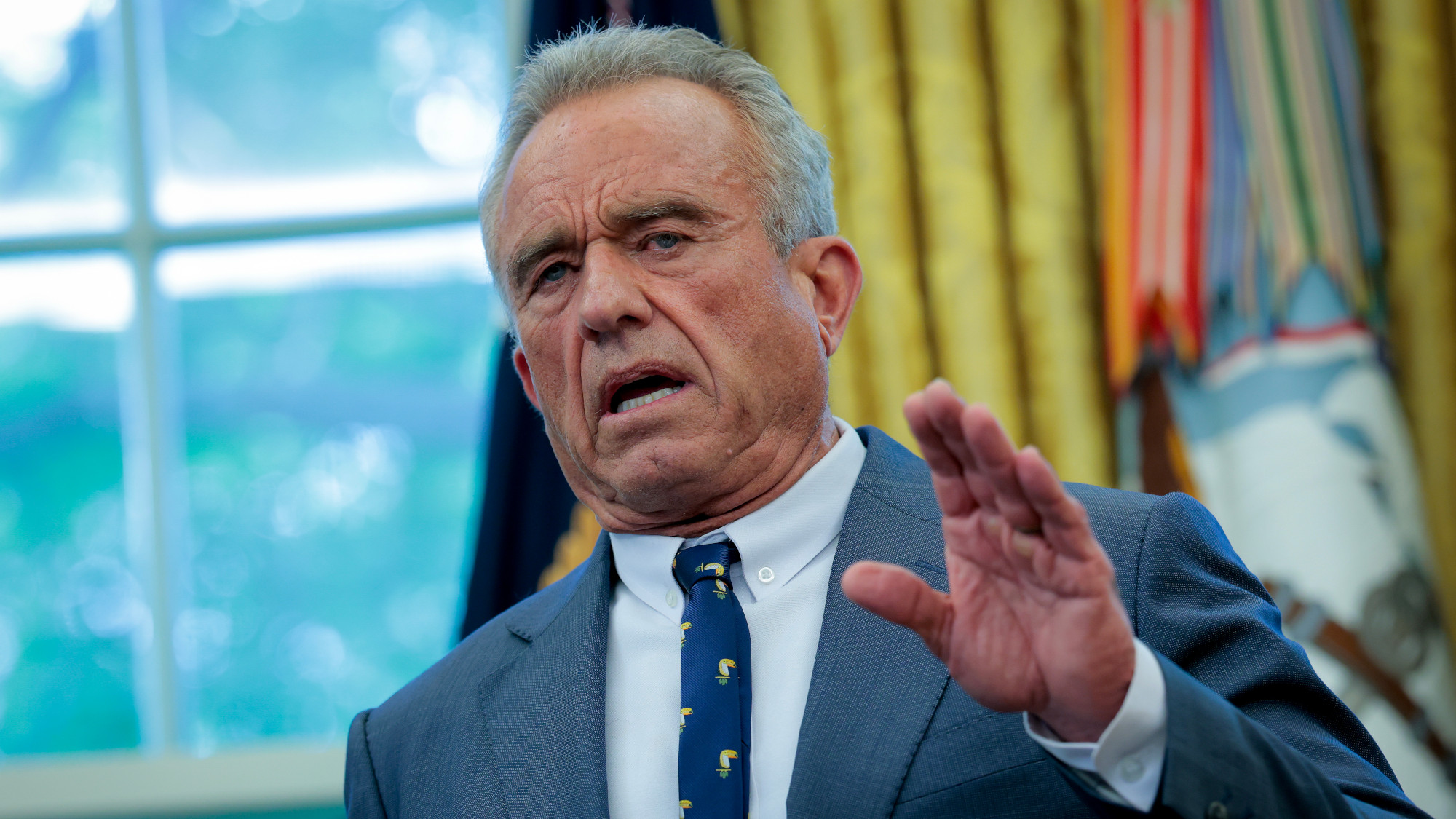

RFK Jr. vaccine panel advises restricting MMRV shot

RFK Jr. vaccine panel advises restricting MMRV shotSpeed Read The committee voted to restrict access to a childhood vaccine against chickenpox

-

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kids

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kidsSpeed Read The Health Secretary announced a policy change without informing CDC officials

-

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sick

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sickspeed read The FDA set stricter approval standards for booster shots

-

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccines

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccinesFeature The Health Secretary announced changes to vaccine testing and asks Americans to 'do your own research'

-

Five years on: How Covid changed everything

Five years on: How Covid changed everythingFeature We seem to have collectively forgotten Covid’s horrors, but they have completely reshaped politics