The Omicron variant might be our last warning about vaccinating Africa

Do you want variants? This is how you get variants.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Over Thanksgiving weekend, global markets were convulsed by news of a new coronavirus variant, dubbed "Omicron" by the World Health Organization after discovery by South African scientists. It raised the prospect of yet another major surge of cases and deaths all around the world.

Though that initial panic may be overblown, Omicron is still extremely concerning — and an object lesson in the crazy risk of letting so much of Africa remain unvaccinated against COVID-19. I and many others have been warning variants would arise there, and now one has. Without rapid mass vaccination, this won't be the last time it happens.

We don't yet know much about Omicron. As virologist Boghuma Kabisen Titanji explains at The Atlantic, it's a variant with a large number of mutations that are associated with increased infectivity and ability to evade the immune system. It's possible that means the vaccines will be less effective, though it's vanishingly unlikely vaccination will provide no protection at all. Booster shots will almost certainly still be useful in limiting Omicron's spread, and a future booster could be aimed specifically at this variant.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Meanwhile, as Cambridge microbiologist Ravi Gupta has said, the genetic profile of these mutations suggest it came from a prolonged, chronic infection of a single person with a compromised immune system. It's exactly the kind of result we'd expect from the virus battering a weak (but not too weak) immune system for months on end, giving the virus selective pressure to learn lots of new tricks.

However, it may also be good news. It's possible Omicron is less deadly than Delta, because a variant that infected somebody with a weak immune system but did not kill them might have effectively learned to produce milder symptoms. For example, mutations to the famous spike protein could make the new variant more resistant to an immune response while also making it less effective at entering human cells. (That could be beneficial in evolutionary terms for the virus itself — after all, a live host who feels well enough to walk around spreading the infection is preferable, in this sense, to a dead one.)

Even if that comparatively hopeful scenario proves correct, however, the point about vaccines in Africa still stands. Variants will emerge when the disease is circulating unchecked, and the next one could easily be much worse.

Now, the South African government is right to complain that it's being singled out and scapegoated here. It's right to point out that travel bans on African countries exclusively make little sense given that Omicron has been detected in several other countries already. (I'd bet it's already present in the U.S. as well.) The world owes South Africa thanks for its extensive system of genetic surveillance, and punishing this good deed won't encourage similar transparency when the next variant emerges.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But it's important to be clear that the variant likely did come from southern Africa somewhere. As I argued way back in early January (and again in May and September), variant risk is the most convincing reason for the rest of world to get off its hind end and start sharing vaccines and providing administrative help in Africa. Eswatini (formerly known as Swaziland), Lesotho, Botswana, and South Africa are all at 19 percent HIV positive or higher — the highest HIV prevalence in the world — and all are in that region. That huge population of immunocompromised people is incredibly vulnerable to the chronic infection scenario described above.

However it won't be as easy as just sending doses. Many African countries are still desperately short of vaccines (Botswana in particular could use more, though deliveries are accelerating), but as I previously wrote, a growing share are running into administrative roadblocks and lack of demand rather than supply shortages. In some countries lack of syringes is the problem, in others it is lack of state capacity or political chaos, and in still others it is lack of uptake — and the latter problem is affecting South Africa in particular.

In August, the South African government had to open up universal vaccine eligibility early for lack of uptake among seniors. Last week it asked Johnson & Johnson and Pfizer to delay future deliveries because it couldn't use up its current supply, despite the fact that only about 35 percent of South Africans are fully vaccinated.

It seems there are a number of factors at work here. South Africa has extreme economic inequality, with a huge population of impoverished, long-term unemployed people living in makeshift settlements. Its state apparatus is mediocre at best, and its ruling party, the African National Congress, has become notoriously corrupt. Former president Jacob Zuma was recently prosecuted for obscene corruption (to be fair, that compares favorably to the American tradition of simply letting criminal presidents get away with it).

On the other hand, there are reportedly widespread worries about side effects, and a fair amount of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories circulating on Facebook or elsewhere online. These aren't just Western imports, either — South Africa unfortunately has its own home-grown tradition of medical quackery. Former president Thabo Mbeki was an AIDS skeptic early in his presidency. He appointed a full-blown nut as health minister who argued against the use of antiretroviral drugs to treat HIV and in favor of ginger and beetroot as the HIV epidemic was in its critical early stages.

Poverty, corruption, state incapacity, poor infrastructure, rampant misinformation — that's a recipe for low vaccine uptake if ever there was one. The easiest thing Western governments could do is open the supply floodgates. (Botswana has just 2.4 million people and an effective government and ought to get priority.) In addition to donated doses, however, the United States government owns patent rights in the Moderna vaccine and could force the company to license the recipe to a South African company called Afrigen that is attempting to build the continent's first mRNA vaccine factory.

But alas, as we're seeing, mere supply is not going to be nearly enough for many African countries. Equipment, money, personnel, education campaigns — what is needed will vary from place to place. Botswana and South Africa are functioning middle-income democracies; other countries will have a much harder time of it. In each case, the international community needs to stop up. Millions of lives and trillions of dollars are at stake.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?Talking Point The Trump administration is applying the pressure, and with Latin America swinging to the right, Havana is becoming more ‘politically isolated’

-

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predators

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predatorsCartoons Artists take on the real victim, types of protection, and more

-

Palestine Action and the trouble with defining terrorism

Palestine Action and the trouble with defining terrorismIn the Spotlight The issues with proscribing the group ‘became apparent as soon as the police began putting it into practice’

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancer

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancerUnder the radar They boost the immune system

-

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the rise

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the riseThe Explainer ‘No evidence’ new variant is more dangerous or that vaccines won’t work against it, say UK health experts

-

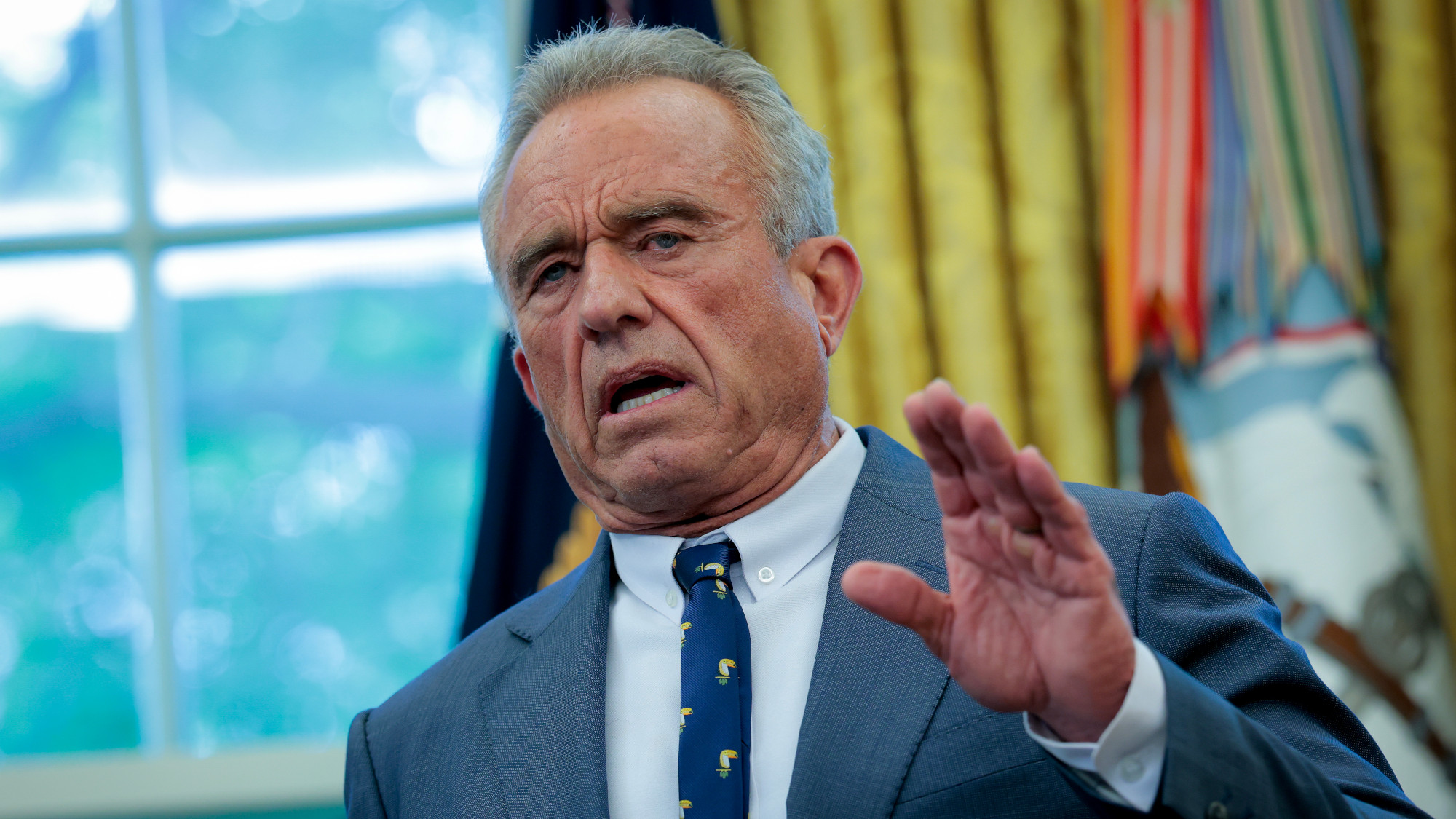

RFK Jr. vaccine panel advises restricting MMRV shot

RFK Jr. vaccine panel advises restricting MMRV shotSpeed Read The committee voted to restrict access to a childhood vaccine against chickenpox

-

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kids

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kidsSpeed Read The Health Secretary announced a policy change without informing CDC officials

-

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sick

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sickspeed read The FDA set stricter approval standards for booster shots

-

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccines

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccinesFeature The Health Secretary announced changes to vaccine testing and asks Americans to 'do your own research'

-

Five years on: How Covid changed everything

Five years on: How Covid changed everythingFeature We seem to have collectively forgotten Covid’s horrors, but they have completely reshaped politics