Will Putin agree to a Ukraine ceasefire in 2024?

Russian leader 'ready to make a deal' amid growing opposition to war but 'no evidence' that Kyiv would cede territory

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Russia has intensified its bombardment of Ukraine, launching one of the most brutal attacks since the war began nearly two years ago.

A total of 158 missiles and kamikaze drones were fired towards six cities over the weekend, reported The Times, with targets including a maternity hospital and a kindergarten. At least four civilians were killed and almost 100 injured, according to UN estimates. The head of the Ukrainian air force said it was the largest missile attack of the war so far.

On Tuesday, Russia fired "a second massive barrage" on Kyiv, said the Financial Times. Ukraine has also "hit back", said BBC News, with attacks on the Russian city of Belgorod that have left 25 dead. In a New Year message, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said Russia would "feel the wrath" of Ukraine's military in 2024.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Vladimir Putin is "buoyed by Ukraine's failed counteroffensive and flagging Western support", said The New York Times (NYT) last month. But "in a recent push of back-channel diplomacy", the Russian leader "has been sending a different message", added the paper. "He is ready to make a deal."

Ttwo former senior Russian officials told the NYT that Putin had been "signalling" that he was "open to a ceasefire that freezes the fighting along the current lines, far short of his ambitions to dominate Ukraine".

What the papers said

"Russia has stockpiled missiles for a winter campaign designed to sap the morale of Ukrainians," said The Times's defence correspondent George Grylls in Kyiv. Ukraine's defence minister told the paper that it was "obvious" that Russia will continue attacking.

But domestic support for the invasion seems to be ebbing. About half of Russians want the war to end in 2024, according to a poll by Russian Field published on Friday. The number who fully support the war has almost halved since February last year, independent polling organisation Chronicle found.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The survey, published in December, "revealed that those who favour peace far outnumber pro-war voices", said Euronews. This is despite the "notoriously difficult" nature of polling in authoritarian states, especially as Moscow has "criminalised criticism of the war and spends millions on pro-war propaganda". Independent Russian polling company Levada found in November that the majority of Russians would support peace talks.

The Kremlin is "likely concerned" about the impact of public opinion on Russia's 2024 presidential election, according to an analysis of Chronicle's findings by US think-tank The Institute for the Study of War. Dissent is growing over mass conscription and poor medical care for soldiers. According to recent US intelligence estimates, Russia has lost "nearly 90%" of the personnel it had when the conflict began, Reuters reported.

Meanwhile, a grass-roots movement has been "gaining momentum" recently, said The Guardian. The movement is led by wives and mothers of some of the 300,000 Russians conscripted in September 2022, an event that triggered a "wave of anxiety and unrest" – and the biggest fall in Putin's ratings since he came to power in 1999. The Russian leader is known to care deeply about such metrics.

Many are "staging public protests", said the paper, and calling for "total demobilisation" of civilian fighters. During the first Chechen war in 1994, a similar anti-war movement of wives and mothers "helped turn public opinion against the conflict and played a role in the Kremlin's decision to stop the fighting".

At the moment, Putin "sees a confluence of factors creating an opportune moment" for a ceasefire, officials told the NYT – a stalemate on the battlefield; Ukraine's stalled counteroffensive; its "flagging support in the West"; and the "distraction" of the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza.

Although the Kremlin "needs a ceasefire", it is "determined to achieve this on favourable terms", wrote Pavel Luzin, senior fellow with the Democratic Resilience Program at the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA), in November. These terms include keeping control over all disputed Ukrainian territory.

However, there is "no evidence" that Ukraine's leaders – who have vowed to retake their territory – would accept such a deal, said the NYT. Ukraine has been "rallying support for its own peace formula", which would require Moscow to surrender captured territory and pay damages.

Zelenskyy said on Tuesday that he saw no sign that Russia was willing to negotiate. "We just see brazen willingness to kill," he said.

What next?

Some argue that Putin "wants to delay any negotiation until a possible return to office" by former US president Donald Trump, said the NYT. But others say the "ideal timing" of any ceasefire would be before Russia's presidential election in March.

Nevertheless, wrote political scientist Luzin, "as during the initial phase of Russia's war of aggression from 2014-2022, there is no doubt that Russia would continue to strike Ukraine even after a ceasefire".

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

Greenland’s capital becomes ground zero for the country’s diplomatic straits

Greenland’s capital becomes ground zero for the country’s diplomatic straitsIN THE SPOTLIGHT A flurry of new consular activity in Nuuk shows how important Greenland has become to Europeans’ anxiety about American imperialism

-

‘This is something that happens all too often’

‘This is something that happens all too often’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Greenland’s capital becomes ground zero for the country’s diplomatic straits

Greenland’s capital becomes ground zero for the country’s diplomatic straitsIN THE SPOTLIGHT A flurry of new consular activity in Nuuk shows how important Greenland has become to Europeans’ anxiety about American imperialism

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

US, Russia restart military dialogue as treaty ends

US, Russia restart military dialogue as treaty endsSpeed Read New START was the last remaining nuclear arms treaty between the countries

-

What happens now that the US-Russia nuclear treaty is expiring?

What happens now that the US-Russia nuclear treaty is expiring?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Weapons experts worry that the end of the New START treaty marks the beginning of a 21st-century atomic arms race

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Which way will Trump go on Iran?

Which way will Trump go on Iran?Today’s Big Question Diplomatic talks set to be held in Turkey on Friday, but failure to reach an agreement could have ‘terrible’ global ramifications

-

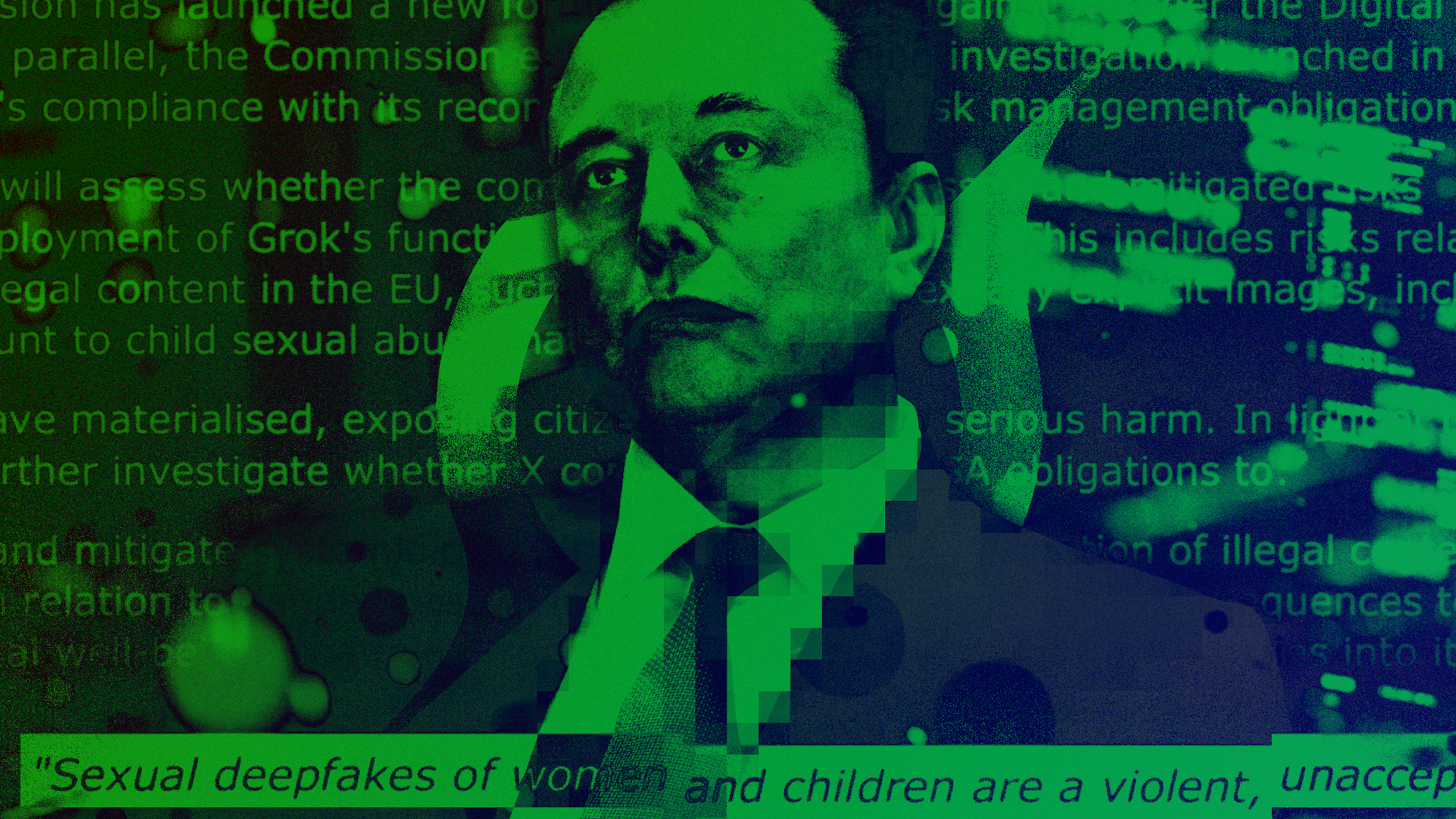

Grok in the crosshairs as EU launches deepfake porn probe

Grok in the crosshairs as EU launches deepfake porn probeIN THE SPOTLIGHT The European Union has officially begun investigating Elon Musk’s proprietary AI, as regulators zero in on Grok’s porn problem and its impact continent-wide