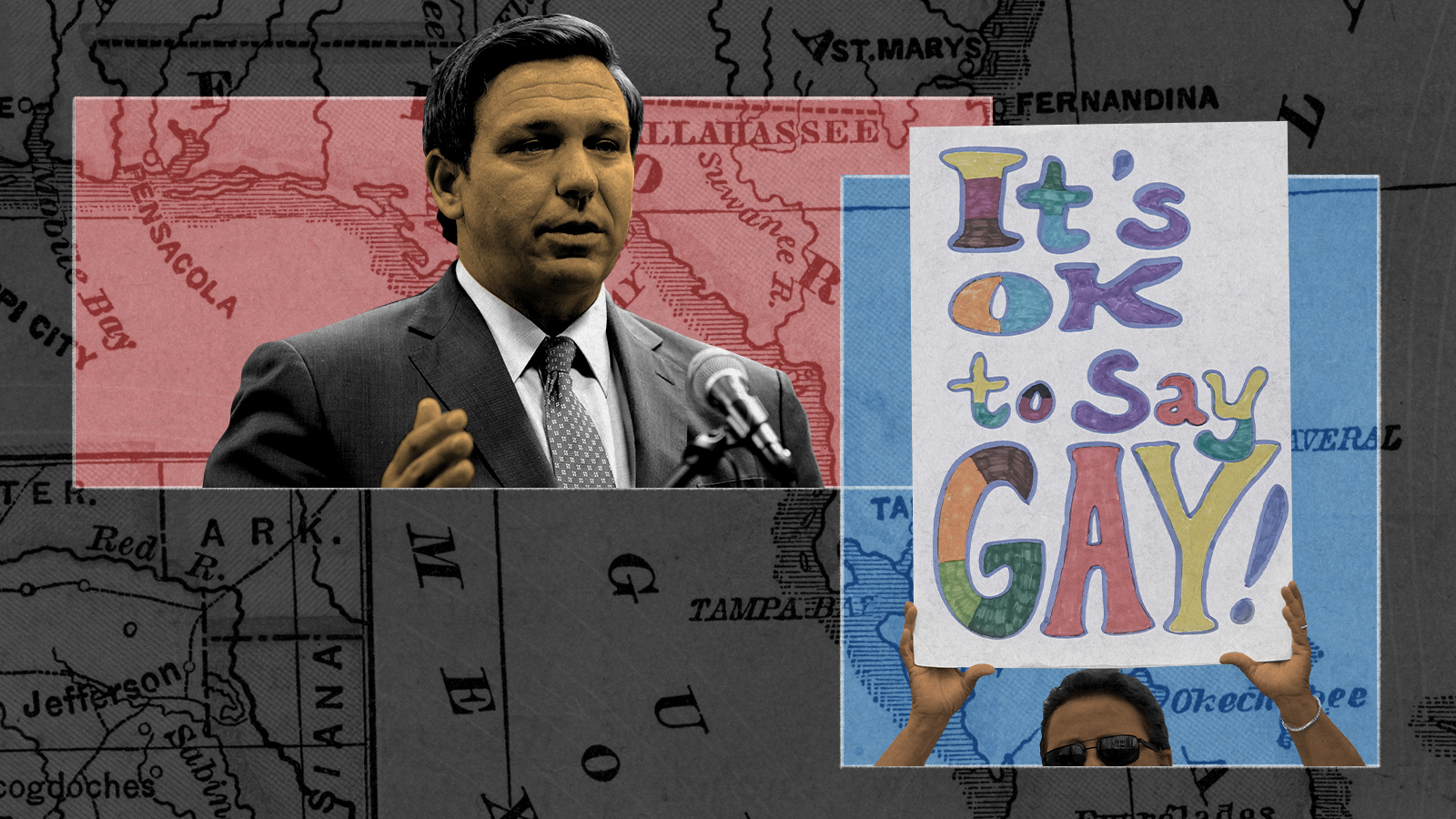

Florida's 'Don't Say Gay' bill, explained

Everything you need to know about the controversial legislation

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A controversial piece of legislation commonly known as the "Don't Say Gay" bill passed the Florida Senate after being approved by the House in February 2022. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) then officially signed the bill into law, which was implemented in July. Since then, corporations within Florida, most notably The Walt Disney Company, have become embroiled in a fight with the governor over the bill. This comes as DeSantis looks to increase his national profile ahead of a likely presidential run and other red states look to follow the governor's lead in implementing LGBT-limiting legislation.

What's the latest?

DeSantis officially passed the controversial bill in March 2022, despite the significant backlash he received. At the signing, DeSantis declared, "I don't care what corporate media outlets say, I don't care what Hollywood says, I don't care about what big corporations say. Here I stand. I'm not backing down."

Some businesses in Florida, including most notably Disney, voiced their opposition. This has led to a significant legal battle between DeSantis and the Mouse House, with the governor moving to take control of Disney World's governing jurisdiction and tax district through a hand-picked board. Disney hit back, though, stripping DeSantis' board of most of its power. This has resulted in both DeSantis and Disney suing each other in a case that isn't likely to be resolved anytime soon.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Even as this legal battle continues, DeSantis has worked to expand the bill by approving a ban on all classroom instruction on sexual orientation and gender identity from grades four through 12, The Associated Press reports. The original bill, known as the Parental Rights in Education Act, had only restricted discussion of these topics from kindergarten to the third grade. Florida's House of Representatives has also moved to enact similar legislation backed by DeSantis, AP notes, including restrictions on gender-affirming treatment, bathroom use, and the legality of children in drag shows. Many of these types of restrictions have since spread to other conservative-led states.

What was in the original bill?

The original text of the bill, which was filed on Jan. 11, 2022, by Florida state Rep. Joe Harding (R), stipulates that "[c]lassroom instruction by school personnel or third parties on sexual orientation or gender identity may not occur in kindergarten through grade three or in a manner that is not age appropriate or developmentally appropriate."

"If that language seems vague, it is," explains CNN. "But vague legislation can have massive consequences."

The bill also empowers parents to sue schools and teachers that violate this ban, enhancing the ability of Florida's parents to object to their children's curricula.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Notably, the "Don't Say Gay" nickname was created and spread by activist opponents of the bill. The bill does not seek to prohibit the use of the word "gay" in schools, its supporters note.

Are schools forced to "out" LGBT students?

Maybe.

The final text of the bill requires schools to notify parents "if there is a change in the student's services or monitoring related to the student's mental, emotional, or physical health or well-being." A student coming out as transgender or nonbinary would require changes to the student's "services and monitoring," such as altering the student's gender marker in school records or stipulating the use of different pronouns in the classroom, and could therefore fall under this definition.

The legislation does, however, include a carve-out that allows schools to "withhold such information from parents" when there's a risk of "abuse, abandonment or neglect." So, for example, a transgender student who wears girls' clothes and uses a feminine name at school but lives as a boy at home because of parental threats would not have to be "outed."

An amendment Harding introduced in February 2022 would have required schools to "develop a plan … to disclose such information [to parents] within six weeks" even if "a reasonably prudent person would believe that disclosure would result in abuse, abandonment or neglect," but Harding withdrew the amendment a few days later.

Have other states followed suit?

Yes. In the aftermath of the bill's initial proposal, more than a dozen states considered legislation that would place similar bans on classroom sexual education, NPR reports, with bills that "in several ways will mirror Florida's new controversial law." While the proposals vary between states, the majority "seek to prohibit schools from using a curriculum or discussing topics of gender identity or sexual orientation."

Arjee Restar, an assistant professor of epidemiology at the University of Washington, told NPR the bills go beyond just legal framework and are "an overt form of structural transphobia and homophobia, and it goes against all public health evidence in creating a safe and supportive environment for transgender, nonbinary, queer, gay and lesbian youths and teachers to thrive."

Alabama and Arkansas have already enacted laws signed by their respective governors, AP reports, noting that at least 30 proposals have been put forth similar to Florida's law in states around the country. A bill in Missouri is also pending before their House committee, and Texas Gov. Greg Abbott (R) has similarly discussed prohibiting discussions of gender identity in schools.

This push to ban LGBT issues in the classroom is not new. In 2008, Tennessee State Rep. Stacey Campfield (R) introduced a bill prohibiting "the teaching of or furnishing of materials on human sexuality other than heterosexuality in public school grades K-8." The bill failed relatively quietly.

In 2011, Campfield, by then a state Senator, reintroduced the legislation, which also included language that could be interpreted as requiring educators to "out" gay students to their parents. This time, it attracted national and international attention, and critics quickly coined the phrase "Don't Say Gay" to describe it.

After several years in legislative limbo, Campfield's bill passed the state Senate in 2015 but never became law.

What has the reaction to the bill been?

Proponents of the bill tend to focus on the part that bans instruction on sexual orientation or gender identity "in kindergarten through grade three."

"Ask any non-deranged parent if they want their 6-year-old to talk about their sexuality with their teacher and they'll look at you like you're crazy," Alex Perez wrote at The Spectator World. Harding said the bill is "designed to keep school districts from talking about these topics before kids are ready to process them."

Detractors, meanwhile, emphasize the phrase "in a manner that is not age appropriate or developmentally appropriate," arguing that such imprecise language could lead to lawsuits from parents who believe any discussion of LGBT identities is inappropriate at any grade level.

Amit Paley, the CEO of the LGBT suicide prevention group The Trevor Project, wrote at CNN that the bill "would effectively erase entire chapters of history, literature and critical health information" and "silence LGBTQ students and those with LGBTQ parents or family members." He added that, according to his organization's research, "LGBTQ students who learned about LGBTQ issues or people in classes at school were 23 percent less likely to attempt suicide in the past year."

LGBT advocacy group Equality Florida threatened to "lead legal action against the State of Florida" if "the vague language of this bill" is "interpreted in a way that causes harm to a single child, teacher or family." Kara Gross of the ACLU's Florida branch told Time the bill could infringe on teachers' First Amendment rights.

In his State of the Union speech, President Biden told "younger transgender Americans" he would "always have your back … so you can be yourself and reach your God-given potential."

Some of the bill's critics took its nickname literally. Occupy Democrats writer David Weissman falsely claimed Republicans had "banned the word gay in the state of Florida." Florida state Rep. Anna Eskamani (D) shared a TikTok montage of various people saying "gay" into their phone cameras in protest.

Why has the name of the bill been so controversial?

The bill's full name is almost 400 words long, so naturally, some sort of nickname had to be devised.

Supporters refer to it as the "Parental Rights in Education" bill, but so far, the bill's opponents are winning the PR battle. Google searches for "don't say gay" vastly outnumber searches for "parental rights in education." Media outlets including ABC, The Associated Press, CBS and NBC have referred to the legislation as "Don't Say Gay" in headlines.

When a reporter for Tampa Bay's NBC affiliate used the nickname when asking Gov. DeSantis about the bill, DeSantis accused him of "pushing false narratives."

Christina Pushaw, the governor's press secretary, suggested on Twitter that the legislation ought to be called the "Anti-Grooming Bill." According to the Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network, "grooming" refers to "manipulative behaviors" that a sexual "abuser uses to gain access to a potential victim, coerce them to agree to the abuse, and reduce the risk of being caught." Florida state Rep. Carlos G. Smith (D), who is gay, blasted Pushaw for "openly accus[ing] opponents" of the bill of being "pedophiles."

May 3, 2023: This article has been updated throughout to reflect new developments.

Theara Coleman has worked as a staff writer at The Week since September 2022. She frequently writes about technology, education, literature and general news. She was previously a contributing writer and assistant editor at Honeysuckle Magazine, where she covered racial politics and cannabis industry news.