Why fighting is allowed in ice hockey

Despite controversy, fights are still seen in numerous professional games

Fighting is one of ice hockey's unique elements, and it is the only sport where throwing punches is not only allowed, but sometimes encouraged.

Despite a cooling off in recent years, fighting remains an often integral part of the game; recently, three fights even broke out in nine seconds between the U.S. and Canada at the 4 Nations Face-Off tournament.

What are the rules regarding fighting in ice hockey?

To someone who has never watched hockey, it may seem that the fights involve two players simply dropping their gloves and pummeling each other. However, fighting in most professional leagues is highly regulated and subjected to standards and penalties, both unwritten and written:

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

- Tradition and history: Fighting has been a part of hockey since its earliest days, with the first documented fight occurring in 1890.

- “The code” is an unwritten rule of conduct among players that aims to keep things fair when players do fight and to help determine when fights happen. The CBC’s Fifth Estate series covered the topic in a 2009 episode.

- Building team spirit and changing momentum: Fights can be used by players to boost team morale and energy during a game.

- Entertainment value: Fighting has historically been an entertaining aspect of ice hockey for many fans.

- Role of enforcers: Historically, specific players known as "enforcers" specialized in fighting, though their role is diminishing today.

An official fight occurs "when at least one player punches or attempts to punch an opponent repeatedly," according to the official rulebook of the National Hockey League. A fight may also occur "when two players wrestle in such a manner as to make it difficult for the linesmen to intervene and separate the combatants." Fights may also only be between two players, though multiple fights can happen on the ice at the same time.

There is a wide variety of scenarios that may take place during a game, requiring the need for lengthy explanations within the rulebook. One of the most notable is rule 46.11, often called the "instigator rule." While any player who fights automatically receives a five-minute major penalty, the player deemed to have instigated the fight is subject to additional penalties under this rule. This rule is often heavily scrutinized, as it has "created such costly penalties that teams couldn’t afford to pay the price to put nuisance skaters in their place," said The Hockey Writers.

Other portions of the rules outline penalties for rarer scenarios. This can include players who jump off the bench to start a fight, fighting off of the playing surface and fighting non-player personnel such as coaches, all of which has actually happened.

Why is fighting encouraged in ice hockey?

Fighting is technically a violation of the rules, as former NHL referee Kerry Fraser said to Insider — it just isn't normally stopped once two players start. However, much of the reason fighting has made a mark on hockey is part of a code of conduct among players.

Fights in today's NHL commonly start when one player decides to stand up for his teammate, often following a large hit or other physical altercation. However, given the fast-paced and violent nature of hockey, tempers and emotions often flare. Fighting is "an expected ritual as old as professional hockey itself, especially if a player has laid another one out through a borderline or illegal hit," said The Seattle Times, as the "old axiom from schoolyards and streets applies equally to NHL rinks: Don’t start something you can’t finish."

Much of this all goes back to the unwritten code of conduct that exists in the sport. Bleacher Report documented a number of clear-cut rules that, while not written down, are explicitly understood by all players. One such rule notes that avid fighters, often called "enforcers," should strive to fight players their own size, and that gloves and helmets should be removed prior to the start of the fight to minimize injuries.

This code is understood to be an integral part of hockey, and sometimes players may simply use fights to boost the morale of their team. Oftentimes, the players who fight aren't even mad at each other. During a game in 2017, the San Jose Sharks' Brenden Dillon and the Nashville Predators' Austin Watson were wearing microphones when they decided to fight. As a result, the two could clearly be heard asking each other if they wanted to fight, and then saying, "You done bud?" and "That a boy, good job" when the fight ended.

After they were done throwing punches, the two players could be heard in the penalty box discussing their upcoming summer plans and wishing each other a good rest of the year.

How did fighting in ice hockey get its start?

The history of fighting in hockey is almost as old as the game itself — and literally happened the very first time the puck was dropped. The first-ever game of indoor ice hockey, played in Montreal in 1875, was followed by a fight between "players and spectators and others who wanted to use the arena for skating," according to The Hockey News. The first documented fight during a game reportedly occurred in 1890.

In these early days, the fighting was notably not subjected to rules and physical altercations often turned out much worse. In 1905, a 24-year-old named Alcide Laurin died after being punched and hit in the head with a stick during a game, becoming the first player to die as a result of an on-ice incident. The player who hit him was charged with murder, though he was later acquitted.

How is fighting in ice hockey viewed today?

It is very much still a part of the game, and there is a good chance that a fight could break out at any NHL matchup. However, the practice has reentered the spotlight in recent years due to concerns over links between fighting and brain injuries.

A number of enforcers, many of whom participated in dozens of fights over their careers, have sadly seen their lives cut short. Todd Ewen, an enforcer from the 1980s, took his own life in 2015, and his wife was convinced there was a connection to his style of play. The aforementioned Bob Probert died of a heart attack in 2010, and it was revealed that his brain showed signs of traumatic injuries. This is, unfortunately, just a small sampling of the fighting-prone players who have died at an early age.

With this being said, fighting in hockey has grown significantly more controversial, and some have called for it to be abolished. However, given that it is so deeply ingrained in the sport, it is unlikely that fighting will be completely stopped any time soon. It is becoming clear, though, that players are much more conscious of their health than they were in decades past, and statistics show that fighting is becoming much less commonplace.

In the 2022-23 season, there were only 219 NHL fights through February, according to The Associated Press. Compare this to the 2003-04 season, where there were 789 fights through the same period. That year also featured a brawl between Philadelphia and Ottawa that "still holds the NHL record with an astounding 419 penalty minutes," said the AP.

Other leagues are taking more drastic steps to stop fighting; the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League "has banned fighting" with "strict new penalties such as an automatic game suspension and possible ejection," said Sean Speer, a previous adviser to former Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper. And "few NHL teams carry a so-called enforcer — a one-dimensional fighter — anymore."

The "push to ban or curtail fighting is attributable to various factors," said Speer, mostly including a propensity for injuries. Despite this, fights in the NHL remain allowed — for now.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Justin Klawans has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022. He began his career covering local news before joining Newsweek as a breaking news reporter, where he wrote about politics, national and global affairs, business, crime, sports, film, television and other news. Justin has also freelanced for outlets including Collider and United Press International.

-

Trump threatens Brazil with 50% tariffs

Trump threatens Brazil with 50% tariffsSpeed Read He accused Brazil's current president of leading a 'witch hunt' against far-right former leader Jair Bolsonaro

-

The Red Brigades: a 'fascinating insight' into the 'most feared' extremist group of 1970s Italy

The Red Brigades: a 'fascinating insight' into the 'most feared' extremist group of 1970s ItalyThe Week Recommends A 'grimly absorbing' history of the group and their attempts to overthrow the Italian state

-

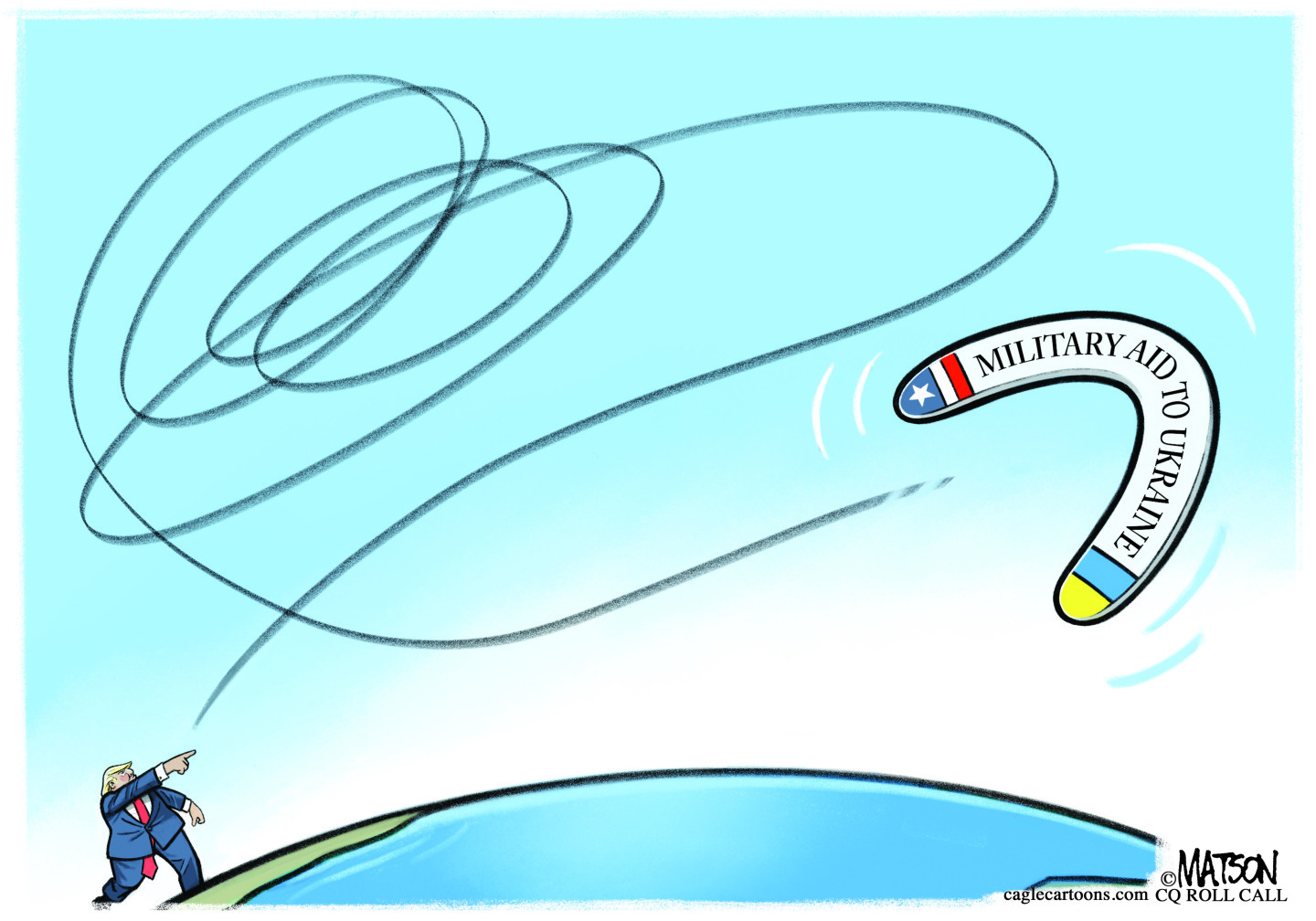

July 10 editorial cartoons

July 10 editorial cartoonsCartoons Thursday's political cartoons include military funding for Ukraine, AI turns Adolf, and a cooling economy

-

The unsteady pace of Formula 1's US popularity

The unsteady pace of Formula 1's US popularityIn Depth The racing sport is immensely popular in Europe but has seen mixed success in the US

-

Kirsty Coventry: the former Olympian and first woman to lead the IOC

Kirsty Coventry: the former Olympian and first woman to lead the IOCIn the Spotlight Coventry, a former competitive swimmer, won two Olympic gold medals

-

Thunder beat Pacers to clinch NBA Finals

Thunder beat Pacers to clinch NBA FinalsSpeed Read Oklahoma City Thunder beat the Indiana Pacers in Game 7 of the NBA Finals

-

World Cup 2026: uncertainty reigns with one year to go

World Cup 2026: uncertainty reigns with one year to goIn the Spotlight US-hosted Fifa tournament has to navigate Trump's travel bans, logistical headaches and an exhausting expanded format

-

Sports betting is causing athletes to be abused and harassed online

Sports betting is causing athletes to be abused and harassed onlineUnder the radar Baseball players, tennis stars and others have raised the alarm

-

Chessboxing: the unique sport becoming a global hit

Chessboxing: the unique sport becoming a global hitUnder the Radar The sport involves a full game of chess interspersed with rounds of boxing

-

Why is the NFL considering banning the 'tush push' play?

Why is the NFL considering banning the 'tush push' play?Today's Big Question The play is widely used by the Philadelphia Eagles, to other teams' chagrin

-

Have the Rockies reached a breaking point?

Have the Rockies reached a breaking point?the explainer Baseball's most aimless franchise takes aim at a record set just last year