How the U.S. can still win in the Ukraine crisis

World War III is the worst scenario. What's the best?

Begun, the Ukraine war has. As of Tuesday morning, the Biden Administration abandoned its earlier caution and pronounced the deployment of Russian troops into parts of Ukraine an "invasion." No casualties have been reported so far, but recent developments are just the latest phase of a conflict that's killed more than 13,000 since 2014.

In fast-moving political crises, it's tempting to concentrate on specific decisions oriented toward immediate effects. Right now, that category includes details of diplomatic rhetoric, targeted sanctions, and reinforcement of allies threatened by Russian moves. The challenge is that it's hard to select tactics or judge their success without a conception of their purpose. We know what Putin wants: the restoration of Russian control over Ukraine, if not outright annexation. What goal is the United States pursuing?

It's easiest to begin with what we don't want: direct clashes between Russian and NATO militaries. Under the terms of the 72-year-old alliance, incursions on the territory of any member or designated NATO forces trigger obligations of collective defense. In other words: World War III.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Such measures wouldn't necessarily or immediately escalate to the disaster scenario, fortunately. In cases of accidental or indirect attack, military and political leaders on both sides would immediately try to prevent escalation. Nor would an encounter between NATO and Russia be the only live conflict between nuclear powers: India and China have skirmished at their borders for decades. Even so, the proximity of Russian and NATO personnel and operations raises the likelihood of an unforeseen encounter. And every such encounter raises the possibility that it will spiral out of control. The administration has never seriously proposed deploying Americans to Ukraine to avoid that nightmare.

Preventing a land-based replay of the Cuban-missile crisis is merely a negative imperative, though. In addition to avoiding the worst, we need some conception of a favorable outcome. Wishful thinking is not a policy. But a vision of success is helpful when it comes to the exercises in ranking preferences and resolving tradeoffs that a realistic strategy requires.

In principle, the answer is easy. We want Russian forces to withdraw within their national borders and to respect the sovereignty of the Ukrainian state. That's been a consistent theme of statements by Secretary of State Antony Blinken and other officials. President Biden reiterated the message in remarks Tuesday.

But our preferred outcome is almost certainly not going to happen. As my colleague Noah Millman has argued, the main reason is that the United States and its allies don't have a lot of leverage. Precisely because we don't want World War III, there's no credible threat of a direct military response. Targeted sanctions could make life uncomfortable for the Russian leadership. Yet more sweeping embargos tend to harm the civilian population while binding it more closely to its government. It's possible that a full-scale invasion would embroil Russia in a long and unpopular war of occupation. But that's not guaranteed: some military experts doubt whether Ukrainians could muster sustained resistance, even with more extensive technological and logistical support.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Russia is not without advantages, either. In particular, Putin may hope to revive the "oil weapon" of the 1970s, using high energy prices to crash Western economies. In a move long-desired by Russian hawks and resisted by domestic constituencies, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz announced on Tuesday that the Nordstream 2 natural gas pipeline between Germany and Russia would be placed on hold. But that resolve could be tested if European consumers and industries feel the pinch of an extended standoff. And Biden faces his own challenges as inflation undermines his popularity at home.

For these reasons, which are far from secrets, it's doubtful that American officials expect a full Russian withdrawal any time soon. Instead, the most appealing realistic scenario is to tempt Russia into aggressive actions that undermine its international status even as it becomes more entrenched in Eastern Europe. In particular, the administration may hope to make China squeamish about providing further support to a disruptive actor. Despite friendly joint statements issued on the opening day of the Winter Olympics, there are hints that the Chinese authorities worry Russia will go too far in provoking the United States and European Union.

Such fears aren't unreasonable. For weeks, European leaders have appealed to the so-called Minsk Agreements of 2014 and 2015 as the basis for a resolution to the conflict. Although the details are complicated, both aimed at the reintegration of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions — where Russia backed dubious separatist movements — with the Ukrainian state. By recognizing their independence rather than just autonomy, Russia has effectively rejected those efforts.

That's bad news for Ukraine, which may end up dismembered and neutralized in a manner reminiscent of the Cold War. But the discrediting of diplomatic efforts could also reawaken the principle of burden-sharing that NATO was established to maintain. The present crisis demonstrates European states can't simply rely on the U.S. to guarantee their security. Poland has already announced increases in defense spending, including a new purchase of American tanks.

Poland is among the most enthusiastic members of NATO and it's too soon to tell whether Russia's recent behavior will tempt other members to follow suit. If they do, though, increased European military activity and cooperation would not only deter Russia from further adventures. It would also help the United States achieve our long-anticipated pivot to Asia by reducing demand to expend scarce resources in Europe.

Although it's an optimistic scenario, that outcome remains far from a permanent answer. The situation could also get worse in any number of ways, even without veering toward nuclear war. In order to maintain the best chance for success, though, we need to think about what a relative "win" might look like. Since Russian submission is unlikely, that's not too much to hope for as the Ukraine crisis continues.

Samuel Goldman is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate professor of political science at George Washington University, where he is executive director of the John L. Loeb, Jr. Institute for Religious Freedom and director of the Politics & Values Program. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard and was a postdoctoral fellow in Religion, Ethics, & Politics at Princeton University. His books include God's Country: Christian Zionism in America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018) and After Nationalism (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). In addition to academic research, Goldman's writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and many other publications.

-

Bad Bunny, Lamar, K-pop make Grammy history

Bad Bunny, Lamar, K-pop make Grammy historySpeed Read The Puerto Rican artist will perform at the Super Bowl this weekend

-

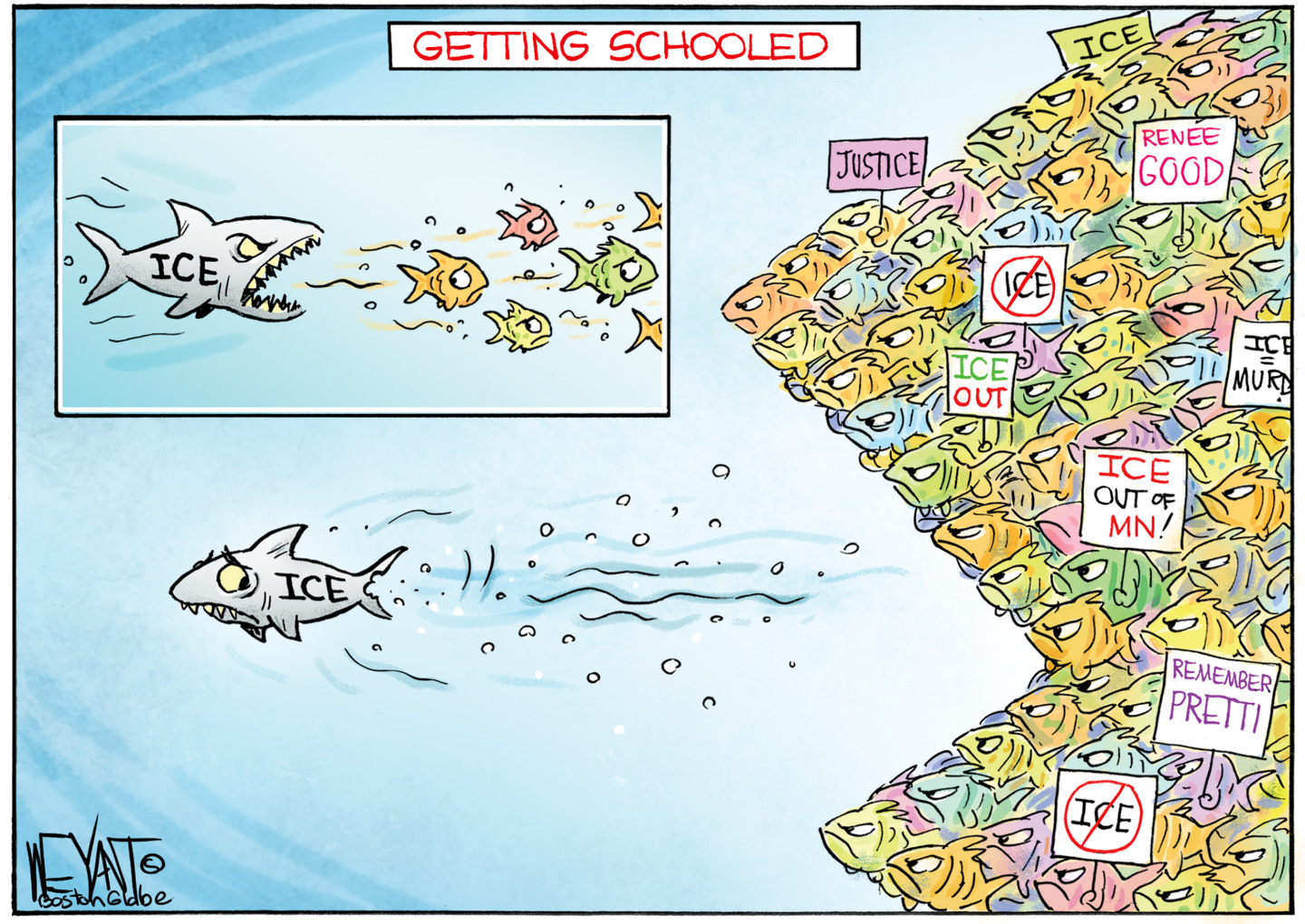

Political cartoons for February 2

Political cartoons for February 2Cartoons Monday’s political cartoons include ICE getting schooled, AI in control, and more

-

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seat

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seatSpeed Read Christian Menefee won the special election for an open House seat in the Houston area

-

What is ‘Arctic Sentry’ and will it deter Russia and China?

What is ‘Arctic Sentry’ and will it deter Russia and China?Today’s Big Question Nato considers joint operation and intelligence sharing in Arctic region, in face of Trump’s threats to seize Greenland for ‘protection’

-

What would a UK deployment to Ukraine look like?

What would a UK deployment to Ukraine look like?Today's Big Question Security agreement commits British and French forces in event of ceasefire

-

Would Europe defend Greenland from US aggression?

Would Europe defend Greenland from US aggression?Today’s Big Question ‘Mildness’ of EU pushback against Trump provocation ‘illustrates the bind Europe finds itself in’

-

Did Trump just end the US-Europe alliance?

Did Trump just end the US-Europe alliance?Today's Big Question New US national security policy drops ‘grenade’ on Europe and should serve as ‘the mother of all wake-up calls’

-

Is conscription the answer to Europe’s security woes?

Is conscription the answer to Europe’s security woes?Today's Big Question How best to boost troop numbers to deal with Russian threat is ‘prompting fierce and soul-searching debates’

-

Trump peace deal: an offer Zelenskyy can’t refuse?

Trump peace deal: an offer Zelenskyy can’t refuse?Today’s Big Question ‘Unpalatable’ US plan may strengthen embattled Ukrainian president at home

-

Vladimir Putin’s ‘nuclear tsunami’ missile

Vladimir Putin’s ‘nuclear tsunami’ missileThe Explainer Russian president has boasted that there is no way to intercept the new weapon

-

The Baltic ‘bog belt’ plan to protect Europe from Russia

The Baltic ‘bog belt’ plan to protect Europe from RussiaUnder the Radar Reviving lost wetland on Nato’s eastern flank would fuse ‘two European priorities that increasingly compete for attention and funding: defence and climate’