French election 2017: Who are the candidates?

As the candidates meet tonight for a televised debate, we look at the main players and what they stand for

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

France's presidential rivals will tonight take to the stage for a televised debate in an election that has got the rest of Europe hooked.

While past elections have been a "two-horse race" between the Socialists and the Republicans, neither of those parties is likely to advance past the first rounds this year.

Francois Hollande's "disastrous" presidency has left his Socialist Party "in tatters", says the Daily Telegraph, while a nepotism scandal involving his Republican rival Francois Fillon has left a vacuum in the political right which moderates fear could be exploited by populist candidate Marine Le Pen.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"Never has a French presidential election captivated so many international commentators before," says the New Statesman.

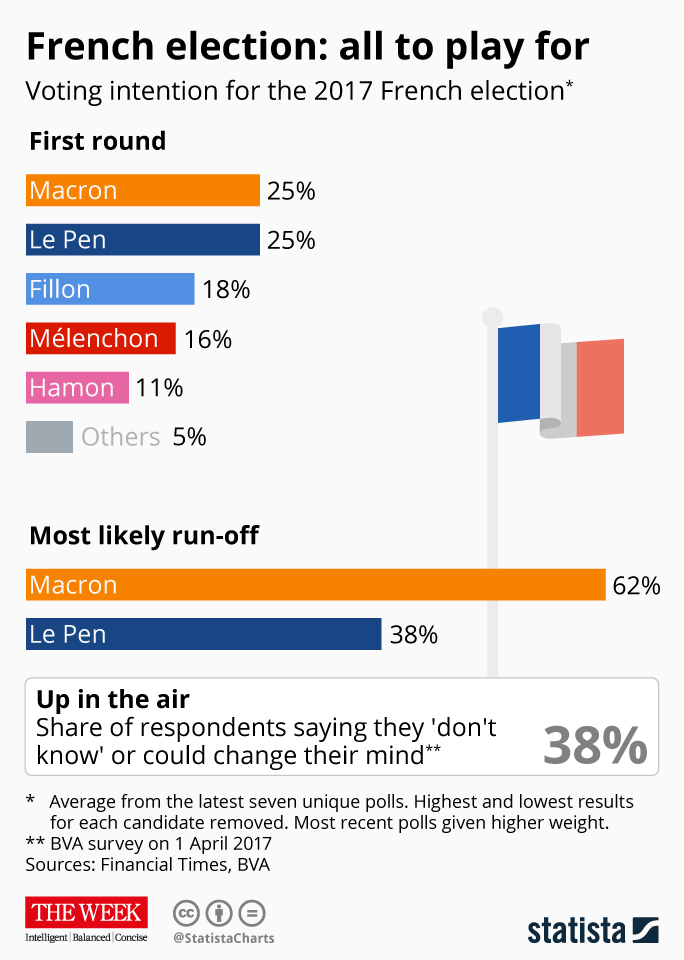

Eleven candidates are in the race, but only a handful stand a serious chance of victory. Currently, Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron are neck-and-neck at the top of the polls, both projected to pull in around a quarter of the vote.

Fillon lags behind with 17 to 20 per cent, while leftists Jean-Luc Melenchon and Benoit Hamon can expect to draw between ten and 16 per cent of the first-round vote.

While political analysts pore over the polls, France's voters remain impatient for answers to the country's major issues: a stagnating economy; a creaking welfare state, and the spectre of domestic terrorism.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How does the French system work?

France elects its president every five years in a two-round system. This year, the first vote falls on 23 April.

If no candidate wins more than 50 per cent of that vote - and given that it is not unusual to see a dozen or more candidates on the ballot paper, so an outright majority is highly improbable - the top two face off in the second and final vote, which takes place on 7 May.

Who are the candidates - and what do they stand for?

Emmanuel Macron, En Marche!: A former banker who served as a finance minister under Hollande before forming his own party in 2015, Macron claims he is "neither of the left not the right".

He started the race as an outsider, but Fillon's campaign-sinking nepotism scandal transformed him into the moderates' hope to keep Le Pen out of the Elysee Palace.

Macron's youthful charisma and slick brand of socially progressive but business-friendly centrism have attracted comparisons with Tony Blair, Justin Trudeau and Barack Obama. Crucially, after a year of Trump and Brexit, victory "would point to a future for centrist, pro-European politics", says The Guardian.

Marine Le Pen, Front National: Le Pen inherited the nationalist party from her father, founder Jean Marie Le Pen. While the Eurosceptic populist remains a controversial figure, due to her inflammatory rhetoric on Muslims, immigrants and refugees, she has tried to soften the party's hard-right image, notably by backing same-sex marriage.

Francois Fillon, Les Republicains: The conservative candidate has spent most of election season embroiled in a protracted scandal concerning his British wife Penelope's lucrative job on the public payroll, resulting in pleas from his own party to step aside.

Fillon has vowed to kick-start France's stagnating economy by cutting red tape, raising the retirement age to 65 and reducing the size of the government by cutting 500,000 civil service jobs.

Jean-Luc Melenchon, La France Insoumise: Like Macron, Melenchon quit his previous party, the Left, to start his own grassroots political movement. La France Insoumise (Unsubmissive France) offers a radical socialist platform, including a 32-hour working week, wealth redistribution and a universal basic income.

His candidacy is expected to split the left-wing vote in the first round of voting, meaning that both Melenchon and the Socialist Party's Benoit Hamon are unlikely to progress to the run-offs.

Benoit Hamon, Parti Socialiste: The Socialist Party is facing an uphill battle against the overwhelming unpopularity of Hollande – although his 22 per cent approval rating is a marked improvement from last year's low of four per cent.

Hamon's pro-worker, pro-environment platform overlaps significantly with Melenchon's, to the point that tens of thousands signed a petition calling on the pair to form a left-wing coalition, although no alliance ever materialised.

Infographic by www.statista.com for TheWeek.co.uk.