How viruses can help fight antibiotic-resistant infections

So-called phage therapy could be the next big thing

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

First, the bad news: Thanks to repeated drug exposure, climate change and air pollution, some infections are developing resistance to antibiotics, a problem that could have global repercussions as diseases become stronger and more prevalent. The good news? Scientists are currently considering an unexpected solution.

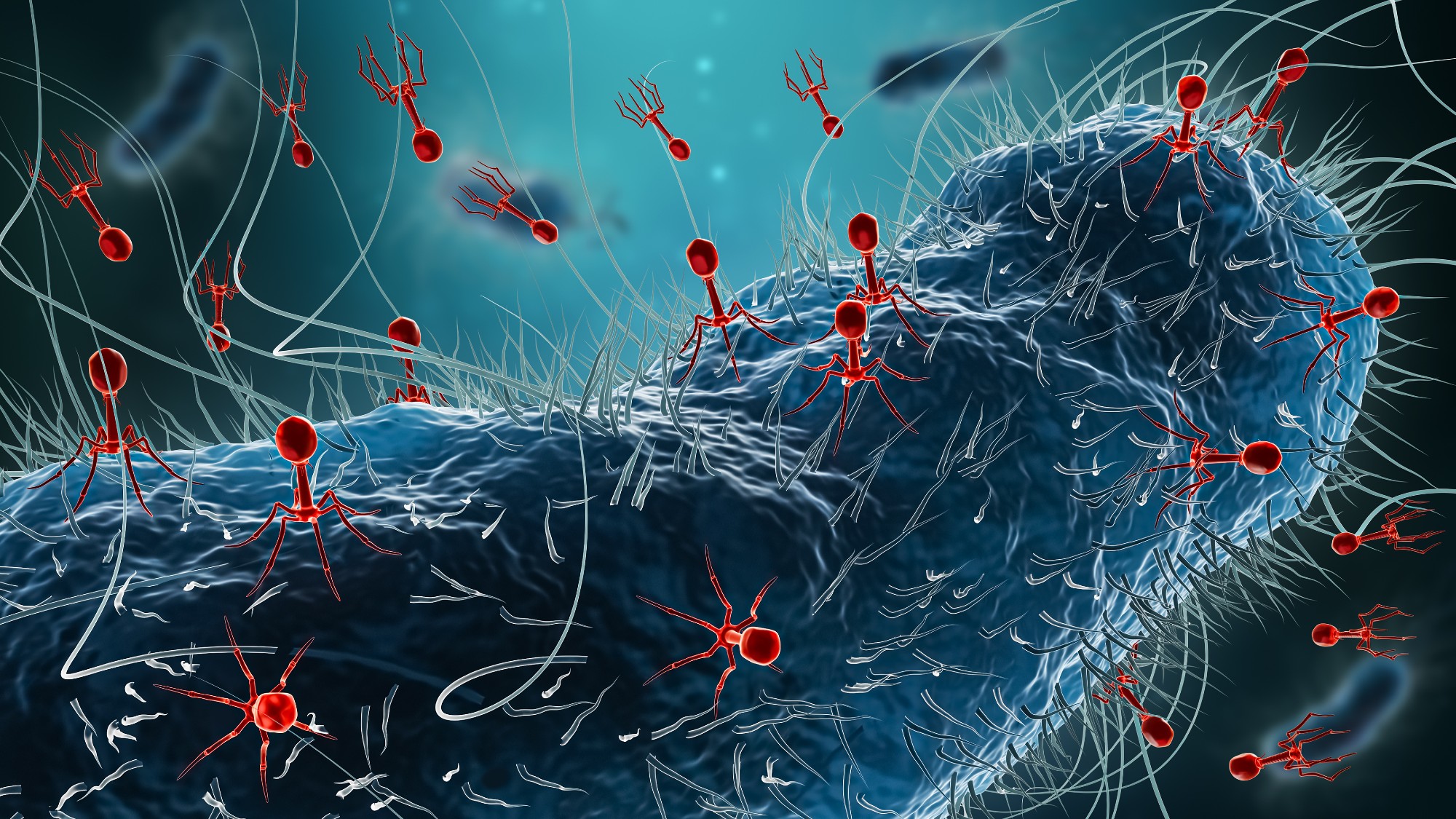

Researchers are looking to bacteriophages, or viruses that specifically target bacteria, to help cure infections. "Phages are the most abundant biological form on the planet," microbiologist Bryan Gibb, an associate professor of biological and chemical sciences, told News Medical. "These naturally occurring viruses are professional bacterial assassins." Experts in the medical field have become more invested in so-called phage therapy as antibiotics meanwhile become less effective.

Phage therapy is currently considered experimental in the U.S. and “can only be used in emergency or compassionate use cases when few or no other treatments are available," Popular Science wrote. It can be administered "intravenously, orally, topically, or intranasally." Though it's considered safe, the efficacy of the treatment has received "mixed reviews." However, "this may reflect a poor match between the selected phage and the bacteria it was meant to target." With more research, phage therapy could become more widespread and potentially cheaper than antibiotics. "One of the biggest hurdles to making this treatment mainstream, aside from regulation, is a lack of awareness around phage therapy's life-saving potential," Maclean's Greg German explained. “Antimicrobial resistance is a battle that can't be won on one front. It's going to take every weapon we've got."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers

-

The 10 most infamous abductions in modern history

The 10 most infamous abductions in modern historyin depth The taking of Savannah Guthrie’s mother, Nancy, is the latest in a long string of high-profile kidnappings

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue Tui after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

Is the US about to lose its measles elimination status?

Is the US about to lose its measles elimination status?Today's Big Question Cases are skyrocketing

-

A real head scratcher: how scabies returned to the UK

A real head scratcher: how scabies returned to the UKThe Explainer The ‘Victorian-era’ condition is on the rise in the UK, and experts aren’t sure why

-

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinations

Trump HHS slashes advised child vaccinationsSpeed Read In a widely condemned move, the CDC will now recommend that children get vaccinated against 11 communicable diseases, not 17

-

Deaths of children under 5 have gone up for the first time this century

Deaths of children under 5 have gone up for the first time this centuryUnder the radar Poor funding is the culprit

-

Stopping GLP-1s raises complicated questions for pregnancy

Stopping GLP-1s raises complicated questions for pregnancyThe Explainer Stopping the medication could be risky during pregnancy, but there is more to the story to be uncovered

-

Nursing is no longer considered a professional degree by the Department of Education

Nursing is no longer considered a professional degree by the Department of EducationThe Explainer An already strained industry is hit with another blow

-

Vaccine critic quietly named CDC’s No. 2 official

Vaccine critic quietly named CDC’s No. 2 officialSpeed Read Dr. Ralph Abraham joins another prominent vaccine critic, HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.