‘Empire of pain’: the rise and fall of the Sackler family

Bankrupt former makers of OxyContin ‘close’ to agreeing settlement over US opioid epidemic

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The billionaire former owners of OxyContin-maker Purdue Pharma are on the verge of a deal that will massively increase their financial contribution to a nationwide US opioids settlement, a new court filing reveals.

Members of the Sackler family agreed last year to pay $4.325bn “to resolve private and public claims against the bankrupt maker of OxyContin and fund opioid relief and education programmes”, ABC News reported.

But after eight US states objected to the bankruptcy reorganisation plan, the family are now “close to an agreement in principle that provides for substantial additional” contributions “that would be used exclusively for abatement of the opioid crisis”, according to a filing by the judge mediating the dispute.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

‘Empire of pain’

The Sacklers were once “famous in cultural and academic circles for decades of generous philanthropy towards some of the world’s leading institutions”, The Guardian reported in early 2018, a year and a half before Purdue Pharma filed for bankruptcy.

But a “wave of lawsuits” linked to the source of their vast wealth, the painkiller OxyContin, saw the “sprawling” transatlantic dynasty descend into “feuding”.

Their business empire dates back to 1952, when three brothers – Arthur, Mortimer, and Raymond Sackler – bought a small pharmaceutical company, Purdue-Frederick. Raymond and Mortimer ran the medicinal side of the company, while Arthur, the eldest of the siblings, led on advertising.

Often described as the Sackler family patriarch, Arthur devised a new way of marketing medical products by reaching out directly to prominent physicians to endorse Purdue-Frederick’s products. This pioneering strategy quickly racked up huge profits, some of which were used by Arthur to become a leading art collector who donated a string of priceless items to museums worldwide.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Arthur died in 1987, nine years before the company, renamed Purdue Pharma, launched what The Guardian described as a “blockbuster” new painkiller.

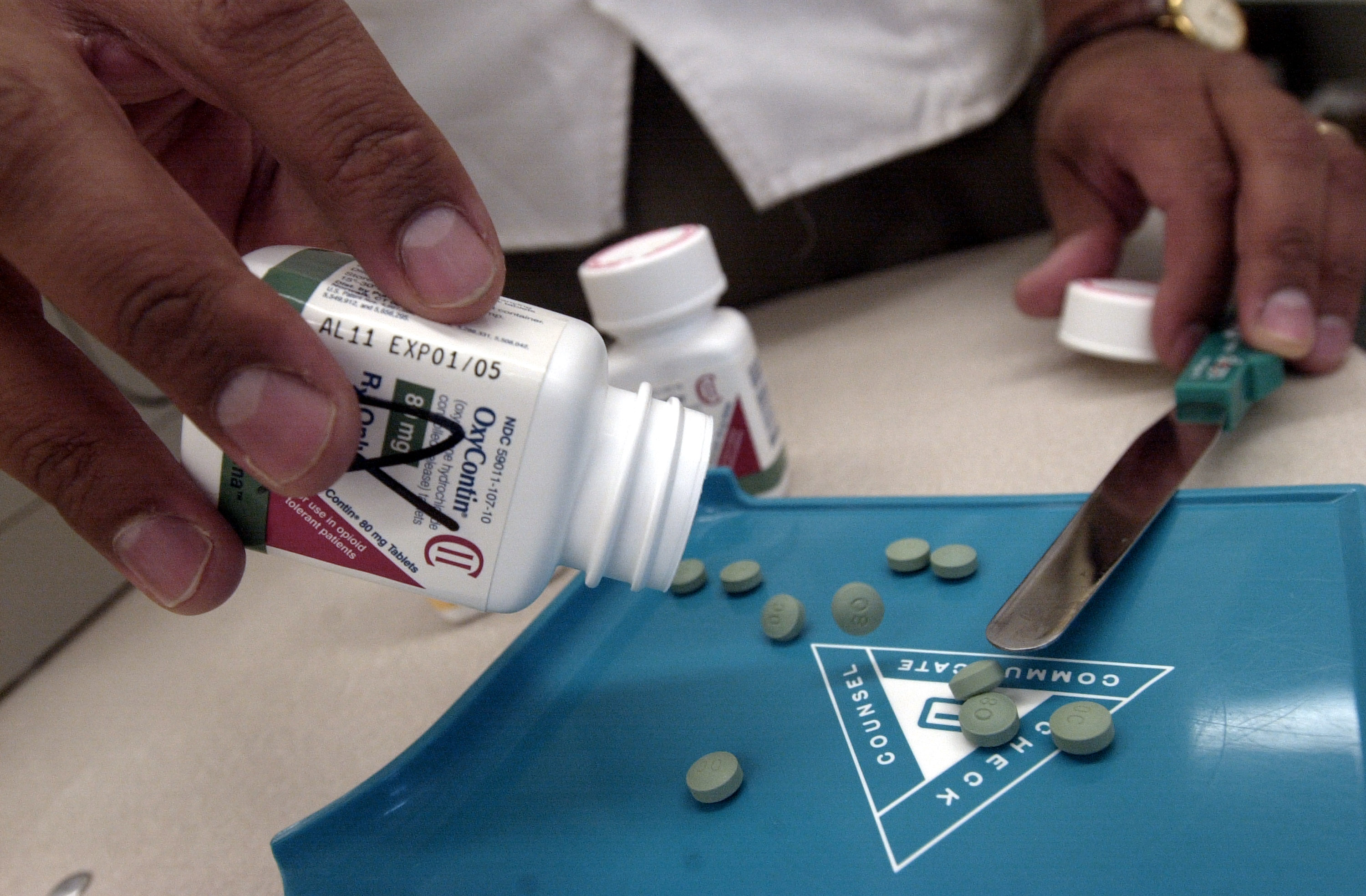

Like Purdue-Frederick products, OxyContin was marketed directly to doctors. But the drug “was stronger than morphine and sparked the opioid crisis that’s now killing more than 100 people a day in America”, said the paper.

Members of the Sackler family’s links to this opioid crisis have been explored in Empire of Pain, a book published last year by award-winning author Patrick Radden Keefe. He told The Times that he was drawn to writing about the family while researching a separate story about Mexican drug cartels.

Drug gangs had “noticed that Americans addicted to prescription opioids were suddenly having trouble finding a hit”, he said. The reason, according to Keefe, was that Purdue had made OxyContin “harder to crush and, therefore, harder to snort or dissolve and inject”.

“US sales of the 80mg OxyContin pill plummeted 25% overnight,” the paper reported.

In other words, said Keefe, what was “clear to anyone with eyes in their head was that 25% of the revenue generated by Purdue Pharma’s biggest pill was coming from the black market”.

Opioid crisis

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “nearly 500,000 people died from an overdose involving any opioid” between 1999 and 2019. The first wave of US deaths was sparked by “increased prescribing of opioids in the 1990s”, followed by a second wave in 2010, “with increases in overdose deaths involving heroin”.

The third wave of fatalities was linked to “synthetic opioids, particularly those involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl”.

“The number of drug overdose deaths increased by nearly 5% from 2018 to 2019 and has quadrupled since 1999,” the public health agency reported.

Against this backdrop, reports that members of the Sackler family knowingly marketed a type of drug that has been “linked to more than 500,000 deaths across the country in the past two decades” caused national outrage, Al Jazeera said.

Investigations by journalists such as Keefe found that the family had “abused America’s commercialised health system to market OxyContin aggressively, even though they knew it fuelled the opioid crisis”, The Times reported.

“To persuade doctors to prescribe it and patients to start using it, Purdue offered both free 30-day subscriptions,” the paper continued.

And “as sales of the 80mg tablet soared, partly due to abuse, they rolled out a 160mg tablet”. The higher dose was “so potent, a single pill could kill”.

The widespread use of the drug “spawned millions of addicts”, said The Guardian, and triggered “a wave of lawsuits alleging ongoing deception about the safety of OxyContin, which the company had previously admitted misbranding in a 2007 criminal case”.

Former Mississippi attorney general Mike Moore, a key litigator in one ongoing case involving Purdue Pharma, told the paper that “greed” was the driving factor behind the family’s marketing of the drug.

“The market for OxyContin should have been much, much smaller,” he said. “But they wanted to have a $10bn drug and they didn’t tell the truth about their product.”

In October 2020, the company reached a settlement worth around $8.3bn, admitting that it “knowingly and intentionally conspired and agreed with others to aid and abet” doctors dispensing medication “without a legitimate medical purpose”.

Under the deal, members of the Sackler family agreed to pay an additional $225m, and Purdue Pharma was shut down.

But the deal has not ended the family’s legal woes. In March 2021, the US House of Representatives introduced a bill that would stop the bankruptcy judge in the case from granting members of the Sackler family legal immunity during the proceedings.

Disgraced philanthropists

The family is now facing a backlash over their widespread philanthropic spending.

When journalist Keefe realised the scale of the drug scandal, he questioned whether it could be “the same family whose name was on the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York that he used to visit when he was a student in Manhattan, and also adorned artistic institutions in Washington and London”, The Times said.

After company founder Arthur kicked off the tradition, the family has handed over huge quantities of art to collections in countries across the globe. And through The Sackler Trust, they have donated “more than £60m in support of charitable activities in the fields of medical science, healthcare, and access to education and the arts” in the UK alone since 2010, according to the charity’s website.

“There was a family that had made billions of dollars from the sale of a drug that had such a destructive legacy yet hadn’t seemed touched by that legacy,” Keefe said. “Looking for the Sackler name on the website of the company they own, I could not find it anywhere.”

Members of the Sackler family used “billanthropy” to cover their wrongdoing, he added.

But since the Purdue Pharma row erupted, efforts “to strip the Sacklers of the soft power afforded by their philanthropic giving” have been launched, ArtNet said.

London’s National Portrait Gallery “turned down a $1.3m gift” in 2019, and “the South London Gallery, the Tate Modern in London, the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and the Jewish Museum Berlin” also pledged not to take the family’s money, the art-focused news website reported.

In a statement released after New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art dropped the Sackler name from its building in December, the living descendants of Purdue founders Mortimer and Raymond said they had “always strongly supported the Met”. But “we believe this to be in the best interest of the museum and the important mission that it serves”, they added.

Keefe told The Times that “there was a hope in the art world” that the Sackler scandal would not force similar actions by institutions. “Museums and galleries knew there was a whiff of the unsavoury, but they were hoping that people wouldn’t notice,” he said.

“The problem for them is that people did notice.”

Having now “turned the spotlight on the art institutions that took their tainted millions”, the journalist predicted that more would ditch the Sackler name, the paper said, “even if it means breaching the terms of naming rights contracts signed with the family”.

After all, Keefe added, “can you imagine the Sacklers suing to have their name put back up?”

Correction, 5 February 2022: This article has been amended to remove the suggestion that the Sackler family have admitted liability for opioid addiction. The family continues to deny wrongdoing.