Beware the politics of inflation

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Inflation is here, and it's sticking around.

That appears to be the message from Wednesday's news that the Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 5.4 percent in September on a year-on-year basis. That's significantly higher than the Federal Reserve's target of 2 percent and somewhat higher than what analysts were expecting. Then there was the nearly simultaneous announcement that Social Security benefits in 2022 will be increased by 5.9 percent, the biggest cost-of-living adjustment in four decades.

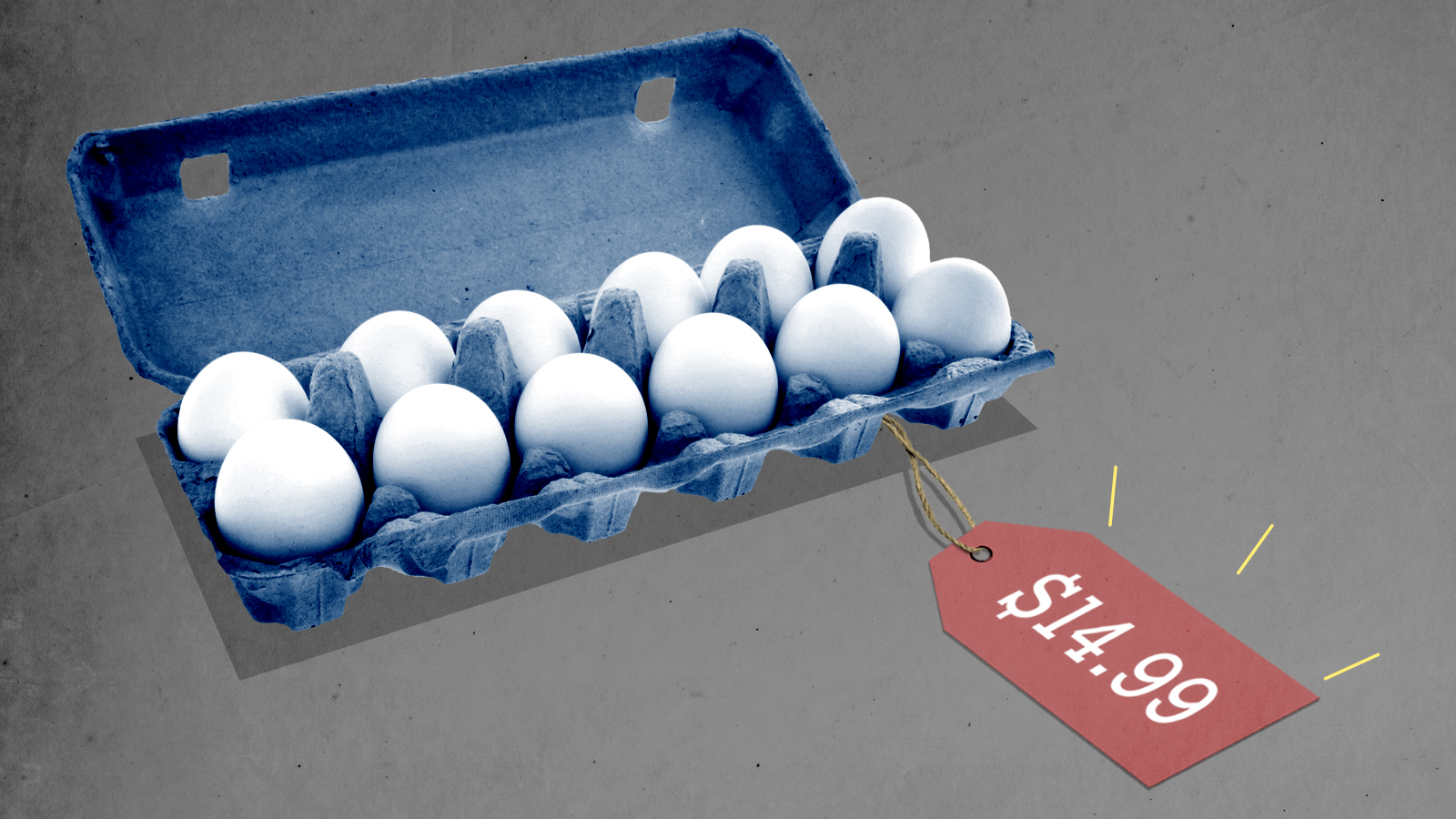

It's not a coincidence that four decades ago was the last time the United States suffered from persistent high inflation. Not that prices are rising as quickly now as they were then, at least at an aggregate level. But on a range of household items — gasoline, used and rental cars, hotels, bacon, beef, pork, eggs, TVs, kids' shoes, furniture — prices are going up at double-digit levels. For the past several months, the conventional wisdom has been that recent price spikes were a function of pandemic-related supply-chain disruptions that should soon be resolved. That might still be true, though everything comes down to what "soon" turns out to mean.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Until we get there, politicians — and especially the Democrats who control the White House and both houses of Congress — will need to adjust to the precarious politics of an inflationary economy. It's been a long time since anyone has needed to do that, and younger pols have no experience of it at all.

When inflation is running high, everyone feels like they're losing ground, growing poorer from week to week and month to month. And unlike with slow growth or lagging job creation, the answer isn't more government spending. In fact, pumping more money into the economy can make things worse. (For that reason, the CPI news is likely to make it more difficult for the reconciliation package currently languishing in Congress to pass in anything like its originally proposed size of $3.5 trillion.)

This is liable to leave Democrats feeling powerless. That feeling could verge into something even darker if the Fed decides to try combatting inflation by raising interest rates, which is also something we haven't seen in a while. Suddenly, talk of the irrelevancy of government debt could be replaced by an anxious concern with the unsustainability of running large deficits, with substantially higher interest payments, from year to year.

As my colleague Noah Millman recently pointed out, an inflationary economy could well favor Republicans, who have historically been more comfortable with emphasizing supply-side issues. And that's obviously on top of the political advantages the GOP will enjoy just by being out of power when inflation became a problem for the first time since the Carter administration. (High inflation continued into the first year or so of the Reagan era, but then it ended and hasn't been a major economic factor since.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Democrats better hope that September's CPI is as bad as it gets and that we soon turn the corner on inflation. How soon? Very soon.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

Are AI bots conspiring against us?

Are AI bots conspiring against us?Talking Point Moltbook, the AI social network where humans are banned, may be the tip of the iceberg

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax

-

Did Alex Pretti’s killing open a GOP rift on guns?

Did Alex Pretti’s killing open a GOP rift on guns?Talking Points Second Amendment groups push back on the White House narrative

-

Washington grapples with ICE’s growing footprint — and future

Washington grapples with ICE’s growing footprint — and futureTALKING POINTS The deadly provocations of federal officers in Minnesota have put ICE back in the national spotlight

-

Trump’s Greenland ambitions push NATO to the edge

Trump’s Greenland ambitions push NATO to the edgeTalking Points The military alliance is facing its worst-ever crisis

-

Why is Trump threatening defense firms?

Why is Trump threatening defense firms?Talking Points CEO pay and stock buybacks will be restricted

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Trump considers giving Ukraine a security guarantee

Trump considers giving Ukraine a security guaranteeTalking Points Zelenskyy says it is a requirement for peace. Will Putin go along?

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story