Extinct volcanos are a treasure trove of elements

Rare earth elements may be a little less rare

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

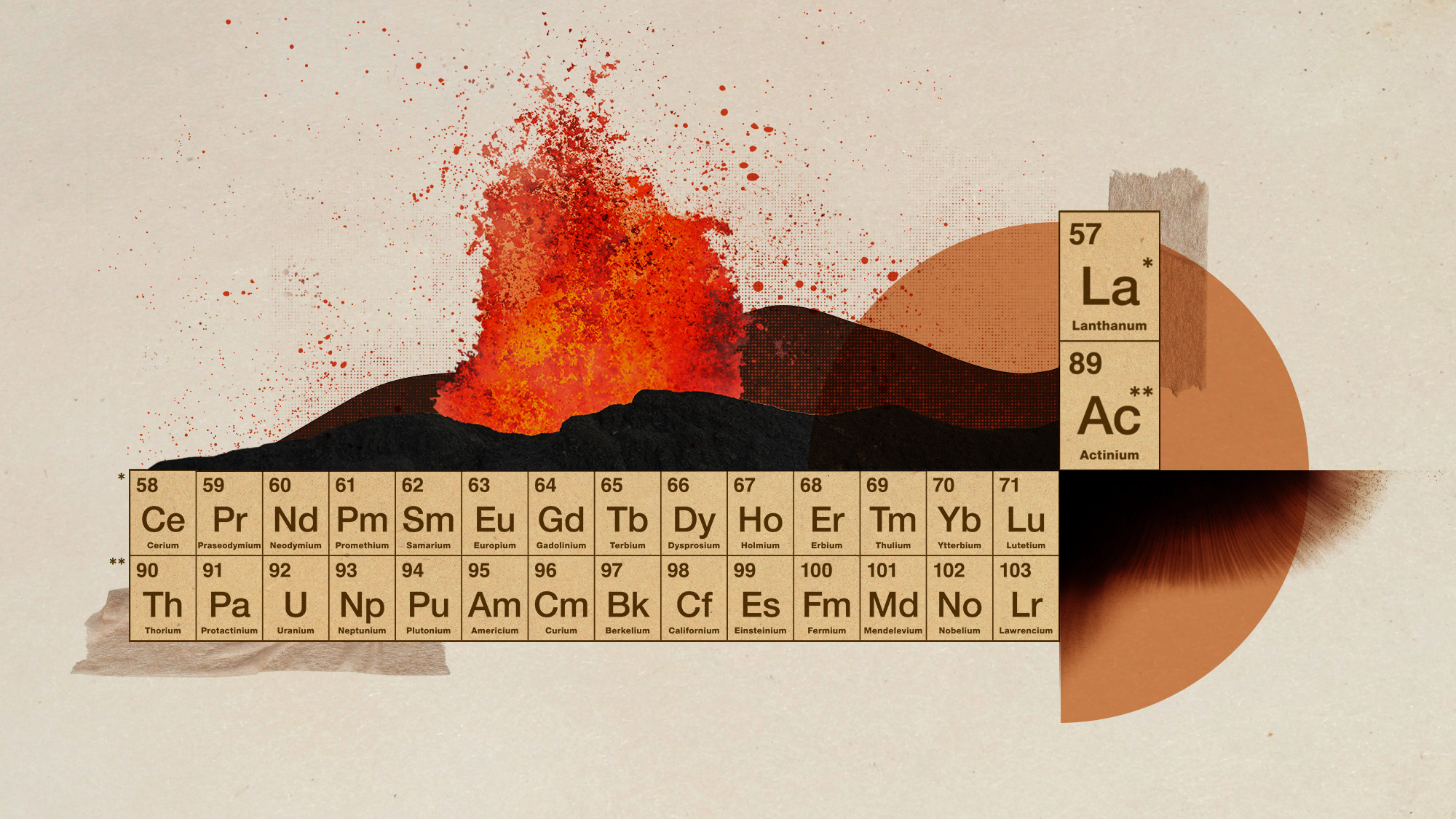

Some extinct volcanoes may be harboring a cache of "rare earth elements," new research has determined. These elements are important for running certain green technologies. The discovery therefore provides a potentially vast and more easily accessible source of materials that will be needed to match a rapidly growing demand.

Metallic volcanos

Volcanoes that have long been dormant may be filled with rare earth elements (REE), according to a study published in the journal Geochemical Perspectives Letters. The source of REE — which are a set of 17 heavy metals — is likely to be iron-rich magma from volcanic eruptions that happened millions of years ago. "We have never seen an iron-rich magma erupt from an active volcano, but we know some extinct volcanoes, which are millions of years old, had this enigmatic type of eruption," Michael Anenburg, one of the study's authors, said in a statement.

Researchers were inspired by discovering a large deposit of rare earth elements in a "mining town that sits upon a huge mass of iron-ore, formed around 1,600 million years ago following intense volcanic activity," said CNN. Was it a "geological accident," or "is there something inherent about those iron-rich volcanoes that makes them rich in rare earth elements?" Anenburg said to the outlet. To answer this question, the scientists simulated iron-rich volcanic activity in the lab and concluded that rare earth elements were indeed present in the magma.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"We found that some rare magma types are surprisingly efficient at concentrating rare earth elements," Anenburg said at The Conversation. "Iron-rich magmas absorb the rare earths so efficiently, their rare earth contents are almost 200 times greater than the regular magmas around them." This opens the door for new sources of these elements, especially since iron-rich magma is easily identifiable.

Sourcing solutions

Rare earth elements like lanthanum, neodymium and terbium are used in powering several clean energy technologies, including electric vehicles and wind turbines. Despite what their name suggests, these elements are not necessarily rare, but they can be difficult to extract. "Just finding rare earths isn't enough," said Anenburg. "You need to have enough of them, you need to have them in the correct minerals, and ideally in a place where mining is feasible." The middle of the desert is good, but a "sensitive rainforest" is less ideal. Mining rare earth elements can also have significant environmental consequences, due to toxic chemicals used in the process polluting the surrounding region. Human rights abuses in the supply chain have also been identified, from the unregulated mines in Myanmar to the use of child labor in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In addition, "our demand for rare earths alone will increase fivefold by 2030," especially as renewable energy technologies become more prevalent, said the European Commission. China currently has the largest deposit of rare earth elements on Earth and remains the main global provider. However, that could change. Extinct volcanoes are already mined for their iron ore, diamond and copper, but the process may be modified to mine for REE as well.

"Findings suggest that these iron-rich extinct volcanoes across the globe, such as El Laco in Chile, could be studied for the presence of rare earth elements," Anenburg said. This would allow for more global sourcing, and would not require the creation of new mines.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

AI surgical tools might be injuring patients

AI surgical tools might be injuring patientsUnder the Radar More than 1,300 AI-assisted medical devices have FDA approval

-

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific research

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific researchUnder the radar We can learn from animals without trapping and capturing them

-

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migration

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migrationUnder the Radar The art is believed to be over 67,000 years old

-

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridge

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridgeUnder the radar The substances could help supply a lunar base

-

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teeth

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teethUnder the Radar ‘There is a corrosion effect on sharks’ teeth,’ the study’s author said

-

The Iberian Peninsula is rotating clockwise

The Iberian Peninsula is rotating clockwiseUnder the radar We won’t feel it in our lifetime

-

The ‘eclipse of the century’ is coming in 2027

The ‘eclipse of the century’ is coming in 2027Under the radar It will last for over 6 minutes

-

NASA discovered ‘resilient’ microbes in its cleanrooms

NASA discovered ‘resilient’ microbes in its cleanroomsUnder the radar The bacteria could contaminate space