The spiritual challenge of multiculturalism

What an obscure 18th-century philosopher can teach us about keeping culturally diverse societies together

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

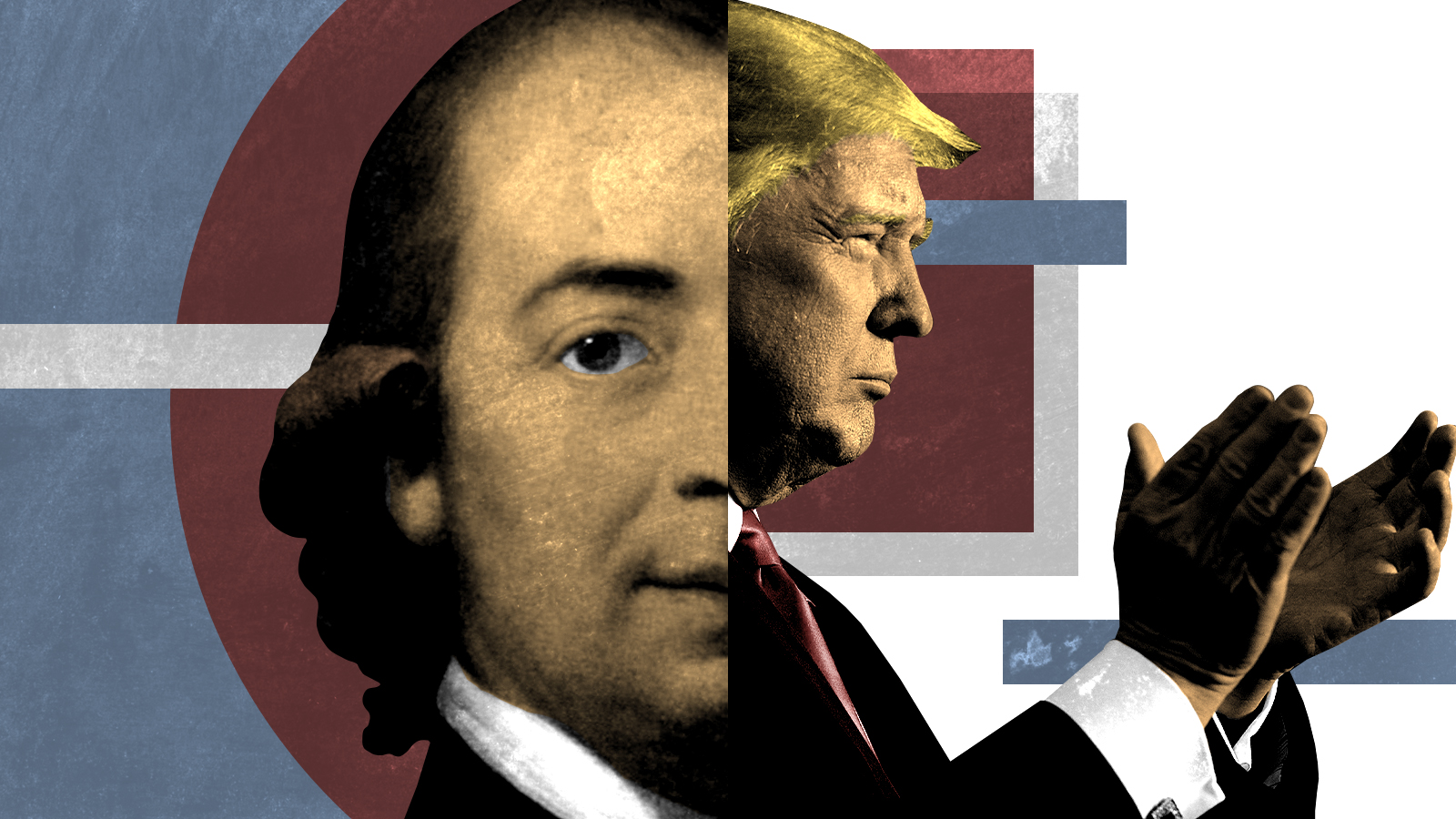

There are many ways to understand the tendency roiling liberal-democratic politics in recent years, from the outcome of the Brexit vote and the presidency of Donald Trump to the surge in support for antiliberal politicians and parties across Europe, Asia, and the Americas. It's been variously described as an explosion of right-wing populism, a resurgence of nationalism, a renewed flowering of xenophobia and racism, even a rebirth of fascism. But what all of these theories are striving to explain is a pervasive collapse of faith in multiculturalism as an organizing principle of free societies.

That feels like a new problem for many of us, but it's really an old one that goes back to the very beginnings of the liberal era. In seeking to come to terms with the challenge of multiculturalism, an obscure but important Geman philosopher of the 18th century, Johann Gottfried Herder, provides suprising insight.

The idea of a multicultural nation-state comes down to us from the Enlightenment. Prior to the 18th century, most political philosophers would have been skeptical about the viability of such a form of political association. The ancient world had small homogeneous city states and vast multicultural empires. Nation states that sit midway between these extremes in size were an invention of the Middle Ages, and they were usually formed from relatively homogeneous ethnic and religious groups. When wars, disease, or economic turbulence exacerbated ethnic fissures in a nation's population or religious passions inspired the proliferation of new sects, the result was often violence, with Europe's religious civil wars of the 16th and 17th centuries the pre-eminent example.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The liberal theory of government that emerged from the aftermath of these wars was designed, in part, to prevent such bloodletting. It would accomplish this goal by getting the state, as much as possible, to focus on protecting individual rights and freedoms — including tolerance for religious and ethnic diversity, and the freedom for groups of individuals to associate in any way they wish within civil society. In American terms, the liberal state gives individuals and groups considerable leeway to define happiness for themselves and focuses on protecting their right to pursue it as they like, while also working to secure the peace and prosperity that allows as many people as possible to do so.

This was the liberal vision of government, and the Enlightenment popularized it, laying a groundwork for the multicultural societies that emerged over the intervening centuries.

Looking at our history in this way is somewhat controversial today, because many historians have emphasized in recent years that the Enlightenment helped to devise and spread theories and practices of racism. There is truth to this, but it's one part of a more complicated story. If the liberalism spread by the Enlightenment could be blended with racism, its political structures also provided a means whereby those excluded from full political power and representation could eventually join in politics and receive the full protection of the liberal state. Which means that, over time, the liberalism of the Enlightenment encouraged the flourishing of multicultural civil societies.

We know this because one of the greatest political achievements of the Enlightenment was the founding of liberal republicanism of the United States, which began by limiting full political rights to property-owning white men but gradually expanded the boundaries of the political community to include white men of more modest means, immigrants from an enormous range of countries, former slaves, women, and other groups. The eventual result was a thriving multicultural polity teeming with citizens from a multitude of races, religions, and regions of the world.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

We also know that multiculturalism is an important legacy of the Enlightenment thanks to Herder. A profound and prolific philosopher, theologian, and poet from Prussia, Herder began his writing career as a severe critic of the most rationalistic strands of Enlightenment thinking for failing to acknowledge and encourage cultural diversity. But by the final decades of his life, Herder had made his peace with the Enlightenment by redefining and expanding its assumptions and goals in a more explicitly multicultural direction.

To the extent that we are wedded to the ideal of a multicultural society, we are all Herder's children. But as important as it may be to acknowledge his neglected historical influence, that isn't the primary reason why his thought is worth taking seriously today. Herder demands our attention because he thought more deeply than we do about the social and spiritual preconditions of multiculturalism — and therefore also about how to fortify its foundations against those whose political projects threaten to undermine it.

In his youth, Herder was a severe critic of the Enlightenment, convinced that its application of scientific reasoning to human societies would dissolve the bonds that hold societies together. He also worried that examining societies in this way would blind us to their distinctive greatness. Understanding and appreciating humanity requires immersing onself in concrete, particular ways of life. It is incompatible with using mathematical and experimental reasoning of the kind favored by such thinkers as Rene Descartes, Francis Bacon, and Thomas Hobbes, who inspired many figures of the Enlightenment to devise universal, one-size-fits-all theories to explain human behavior.

Long before the founding of the social sciences, Herder advocated looking at societies from the perspective of an anthropologist alive to human differences. Each culture and community is, he wrote, a "form of life" with its own "center of happiness within itself," as well as possessing its own form of excellence that should be recognized, preserved, and encouraged to thrive.

At first, his critique of Enlightenment reasoning led Herder to advocate something that sounds remarkably like nationalist purity, with each community hermetically sealed off from the others, organically developing its own cultural and moral system and way of life, resisting the influence of external judgments and critique. Patriotism, rootedness, each nation remaining free of outside interference or criticism — this was the young Herder's ideal. But as his thought matured, Herder came to realize that his own supremely affirmative evaluation of human cultures implied that he, too, was judging them from the outside and on the basis of some external measure. But how was this possible? What was his standard?

Herder's effort to answer these questions propelled him in a direction with profound implications for the self-understanding of the modern societies emerging in his own time. Whether a political community was internally homogeneous or heterogeneous, he claimed, it needed to affirm not only its own distinctiveness and worth, but the distinctiveness and worth of every difference inside of it and outside of it as well. Think of a series of nested dolls or concentric circles. The United States is a heterogeneous community containing people from a multitude of ethnicities, races, religions, and regions of the world, and each of these groups has smaller or narrower groups within it, with diversity increasing the more closely we look. The country as a whole, meanwhile, is somehow the totality of them all — a whole comprised of those parts.

That is the multicultural vision of society. But Herder didn't stop there. On the contrary, he insisted that just as each society as a whole is comprised of many cultural parts, so the world is itself a whole comprised of many national parts, with each country and its distinctive past and present making a unique contribution to the larger whole of "humanity." Going even further, Herder maintained that this larger, global, humanitarian whole needed to be conceived in theological terms.

The reason Herder insisted on supplementing his multicultural theory of society with a theological account of humanity is significant. Multiculturalism, he believed, is intellectually and morally unstable without such a theological foundation to keep it from degrading in one of two destructive directions.

A multicultural society's first vulnerability arises from its members having to live with every group being given equal status. Cultures and communities tend to persist and thrive, after all, by presuming their own excellence. The multicultural outlook both affirms such presumptions and cuts against them by affirming them equally for every culture. This places them on the same level, reducing (in Herder's language) each person to "an insect perched on a clod of earth" and each culture to a lifeless artifact dutifully displayed in a museum of relics. This experience of reduction in cultural status, distinction, and vitality easily develops into despair.

Multiculturalism's second vulnerability moves in the opposite direction, producing individuals and groups that reject the presumption of equal cultural status in favor of outright chauvinism, suspicion, and rank hostility to outsiders, as each person affirms the superiority of her own community, group, or country over the others, "as if their anthill were the universe." When this happens, we see a rise in cultures attempting to impose themselves on others, the outbreak of civil unrest between antagonistic groups in culturally diverse societies, and wars breaking out among nations that find themselves on opposite sides of civilizational chasms.

As far as Herder was concerned, the only way to avoid these fates was for modern, enlightened human beings to cultivate what he called a new "religion of humanity." This religion would treat each and every culture in human history, in the past and in the present, with respect, as contributing to the realization of peace, love, and mutual sympathy. The world that Herder advocates would be one in which Christians, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, and secular men and women within nations throughout the world simultaneously affirm their own religious (or nonreligious) standpoints while also loving, respecting, and sympathizing with those of the others, viewing them all as worthwhile contributions to the divine unfolding of humanitarianism in the world over time.

It's tempting to dismiss Herder's proposal to supplement multiculturalism with a universal religion of humanity as a product of the idiosyncratic, romantic outlook of his own time — at least until we begin to realize that what he's describing resembles in remarkable ways the civil religion that has prevailed in the United States for much of its history.

The Declaration of Independence; the Preamble to the Constitution; the Bill of Rights; Lincoln's Gettysburg and Second Inaugural Addresses; the National Anthem and Pledge of Allegiance; Emma Lazarus' poem inscribed at the Statue of Liberty, describing a nation that welcomes the huddled masses of all faiths who yearn to breathe free; Martin Luther King's calling of the country to fulfill the promises embedded in its founding principles — when Joe Biden talks about America being an "idea," this is what he means. He means the words, principles, creeds, and aspirations that inform our public rituals, animating America's civil religion. To a considerable extent they have fulfilled a function very much like the one Herder assigned to a notional humanitarian faith.

American civil religion has proven itself open to men and women of enormously various faiths, backgrounds, and ways of life. Immigrants, like the descendants of slaves and the continent's native peoples, have faced severe animus in many times and places. But countless millions have also found a place in the United States, becoming colorful tiles in the multicultural mosaic of American life and history, parts forming a complex, always changing, multifarious whole.

Yet America's civil religion is under strain today. The right, preferring a tribal view of the nation, no longer wants to affirm a universal vision of a humanity. Emphasizing a view of the country closer to the young Herder's exclusionary nationalism, populist conservatives prefer homogeneity to diversity, and they mock the pretense of a patriotism rooted in openness to the world and ideas that transcend particulars of time and place. The left, meanwhile, is obsessed with the hypocrisies and shortcomings of the country's civil religion, believing that fulfilling its promise in the future requires a reckoning with past failures so severe that it leaves little place for national pride. Though "woke" progressives respect and valorize cultural diversity for minority groups, they denigrate patriotic sentments as "white supremacy" when they are uttered by white Americans who express admiration for central figures of the country's past.

Herder would not be surprised that maintaining a careful balance between part and whole, particular and universal, national and international has proven to be a challenge — though he would warn us against giving up on trying to preserve that balance through the mediation of a spiritual outlook that both affirms and can be affirmed by every individual and group. That's because Herder believed that a multicultural society might be unsustainable without it.

And he may well have been right.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.